Tire particles chemical harmful to fish prevalent in Delaware River Basin but largely at low levels, researcher says

| October 17, 2025

A chemical added to rubber tires to make them safer for drivers but that pose a hazard to certain fish has surfaced widely in the Delaware River watershed, according to a researcher.

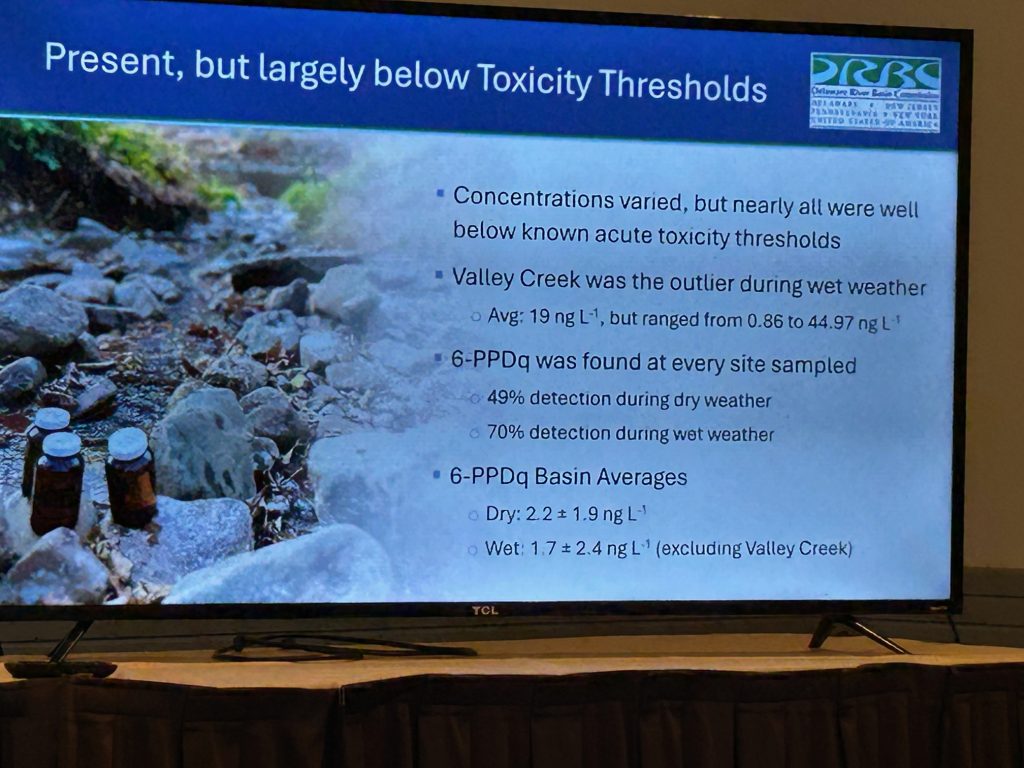

The findings, presented by Jeremy Conkle, a senior chemist and toxicologist with the Delaware River Basin Commission, offered a mixed outlook: On the one hand, the levels detected at sites in the watershed were mostly below acute toxicity levels. However, the long-term effects to fish of prolonged exposure to sub-lethal levels of the chemical remain unknown.

The tongue-twister of a chemical, 6-PPDq, is a byproduct of a polymer that has been added to rubber tires since the 1960s to slow their erosion from dry rot and prevent catastrophic blowouts at high speeds, Conkle said on Wednesday at one of several presentations at the Upper Delaware River Rendezvous, organized by the Friends of the Upper Delaware that was held at the Villa Roma Resort in Callicoon, N.Y.

It’s estimated that up to a dozen pounds of so-called “tire wear particles” are generated per person per year, Conkle said. They end up in a toxic soup of runoff from highways that can include metals, oil, brake dust and other materials cars might shed.

An estimated 10 percent of the tire-shed particles end up in surface waters. For example, the particles are the most common plastic found in the San Francisco Bay, he said.

The push for the chemical additive to rubber tires was accelerated by the car culture that took root after World War II. Cars that might have once topped out at speeds of 25 miles per hour were now zipping along at 50 to 60 m.p.h., making tire safety a greater priority.

Read more: DRBC to study chemical from rubber tire particles as source of water contamination

Manufacturers found 6PPD acted as a sort of rubber preservative and kept tires from drying out and cracking when exposed to ozone, an odorless, colorless gas that occurs naturally in the environment. 6PPD is also found in footwear, synthetic turf and playground equipment.

What happens when tires start to break down

On its own, 6PPD isn’t toxic. But when the rubber flakes and comes into contact with ozone, 6PPD transforms into a byproduct called 6PPD-quinine, or 6PPDq, and it’s now known to have negative to lethal effects on several salmonid species.

The presence of 6-PPDq was noted in the Pacific Northwest for the effect it had on Coho salmon. The gills on the fish would give out after a few hours of exposure to certain levels of the chemical and the salmon would die.

In the beginning, however, the link between 6-PPDq and the die-offs was not immediately clear. The die-off was labeled “urban runoff mortality syndrome” and the precise cause of the fish mortality went under the radar for a long time, Conkle said.

“Nobody knew really what was going on and were looking for that needle in a haystack,” Conkle said.

Though the Delaware River Watershed is not home to Coho salmon, it is home to its “cousin,” such as brook trout, he said.

Varying degrees of harm

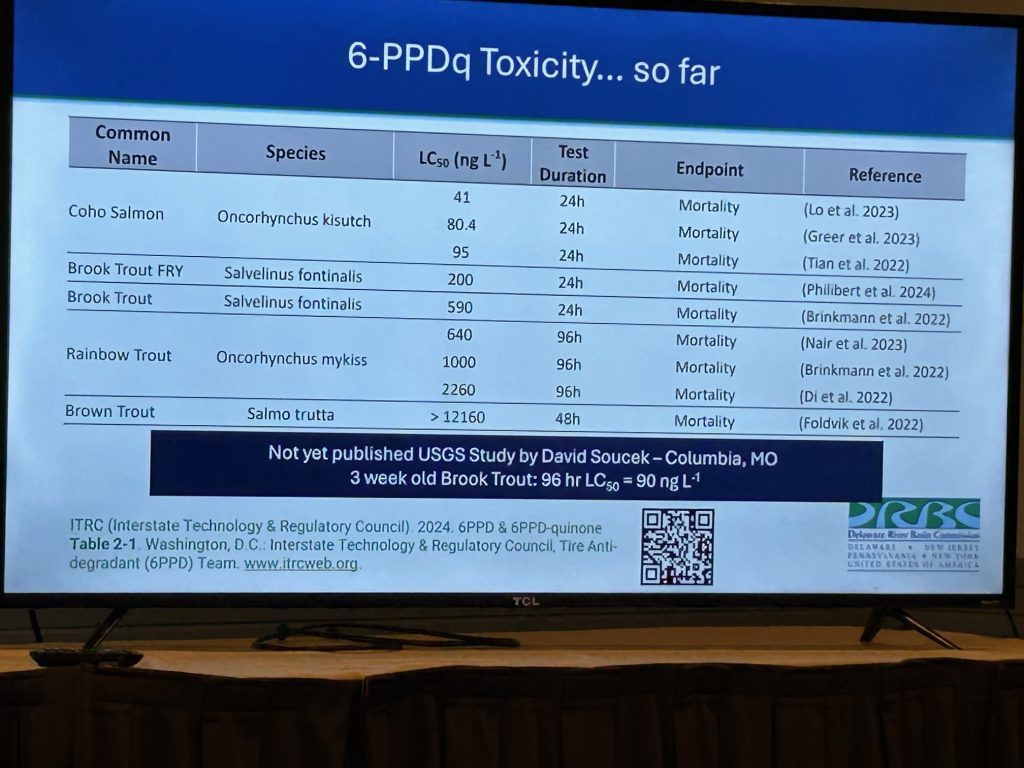

The good news is that the chemical does not tend to linger in water terribly long, about 36 hours. However, testing for prolonged exposure—96 hours in some cases—led to lethal results.

Brook trout fry proved to be the most sensitive to exposure and the adult brook trout less so. Rainbow and brown trout, research indicates, are hardier and more resistant to the effects of the chemical.

“We’re still learning a lot of the behaviors of this chemical,” Conkle said.

Questions though still remain about “sub-lethal” exposure and the long-term effects on the fishes’ ability to breathe, breed and avoid predators. Those effects on the fishes’ gills are less well known. The effects on human health are also unknown, Conkle said.

DRBC researchers tested 13 sites in the watershed between April 2024 and April 2025.

Traces of the chemical were found at every site, even in times of drought but nearly all were found at levels below toxicity thresholds, Conkle said. An exception was sampling done at Valley Creek, near Valley Forge, Pa. The spike in the chemical’s presence there was “pretty serious,” he said.

That outlier was better understood after researchers traced the inflow to the creek and found it was running parallel to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, leading to a direct path into the waterway.

Research is continuing to find a substitute for 6PPD that would prove as beneficial to drivers but less harmful to fish, Conkle said.