Landowners and anglers clash over access in the Upper Delaware River

| October 6, 2025

The mostly placid waters of the two branches of the Delaware River (not very imaginatively named the West Branch and the East Branch) hide a turbulence that only sometimes is visible to the communities nearby.

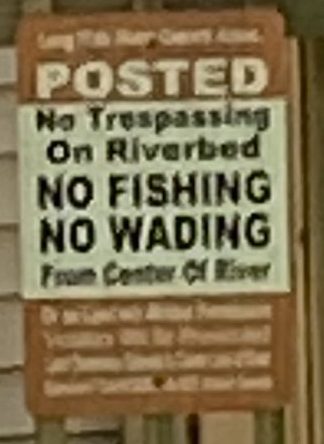

Residents have been alerted to the issue by random unsigned notes dropped into mailboxes in support of river-adjacent landowners who assert ownership of those waters — and the riverbed — through historic right.

If you don’t fish in those waters (the two branches of the upper river), this tempest is mostly in a teapot, but if you do, then it’s a really big deal, and a thorny one, to boot.

The problem, as the landowners see it, is that some people who use the river, like to drop anchor and fish “on their land” in the river.

Landowners claim they have rights to the riverbed from the edge of the river, where it meets their land, up to the center of the river, as the Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation tells the story:

Landowners along the Upper Delaware River own to center of the main channel of the river. In 1708, Queen Anne granted Johannes Hardenbergh 2 million acres in Ulster, Greene, Orange Sullivan and Delaware Counties in New York State, known as the Hardenburg Patent.

Yep, the dispute centers on a land grant from more than three centuries ago.

The Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation, based in Hancock, N.Y., is unabashedly a landowners group as its “Support Our Mission” states: “Your contributions help protect landowners rights and privacy from exploitation along the Upper Delaware River. Join us in making a difference.”

The Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation advocates for those landowners’ rights and has a bias that leans towards those rights. You could investigate the patent further here in a presentation from the Time and the Valleys Museum, or excerpts from a book, “The Catskills: From Wilderness to Woodstock” by Alf Evers.

But that’s really getting into the weeds, which is exactly where some landowners stand.

Some landowners have deeds to their property that reference this land grant, some do not. The grant, in our time, doesn’t confer ownership but rights passed on through previous owners. It has been cited in various deeds in properties that were once part of the patent.

Those who fish on the river believe that the landowners have no right to prohibit them. Sometimes the prohibition is voiced as verbal confrontations, with words exchanged in progressively louder voices from the land side and from boats.

But many people who use the river, including some anglers, don’t know that there’s a problem with who owns the riverbed because they’re not local.

Landowners vs. anglers

Eighty-six percent of anglers are not local, according to a creel survey, part of “Delaware Tailwaters Fisheries Investigation Plan: A Joint Project of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2018-2020.”

Most of the worst excesses are caused by people in boats unfamiliar with the fact that the river here is mostly private property on both banks and they have no knowledge of the ongoing fracas.

Some boaters are bold enough to pull their boats up and park it on private land and picnic by the side of the river, leaving trash for the landowners to pick up, according to Sherri Peters, a landowner near Peas Eddy, on the East Branch, not far from Hancock, N.Y., who is pretty strident in her defense of landowners’ rights.

So, this is battle that is waged in tales told by either side. Who is the “other side” of this tempest?

Basically, it’s all the folks who fish on those waterways, many of whom don’t know about and couldn’t care less about a 300+ year-old land grant.

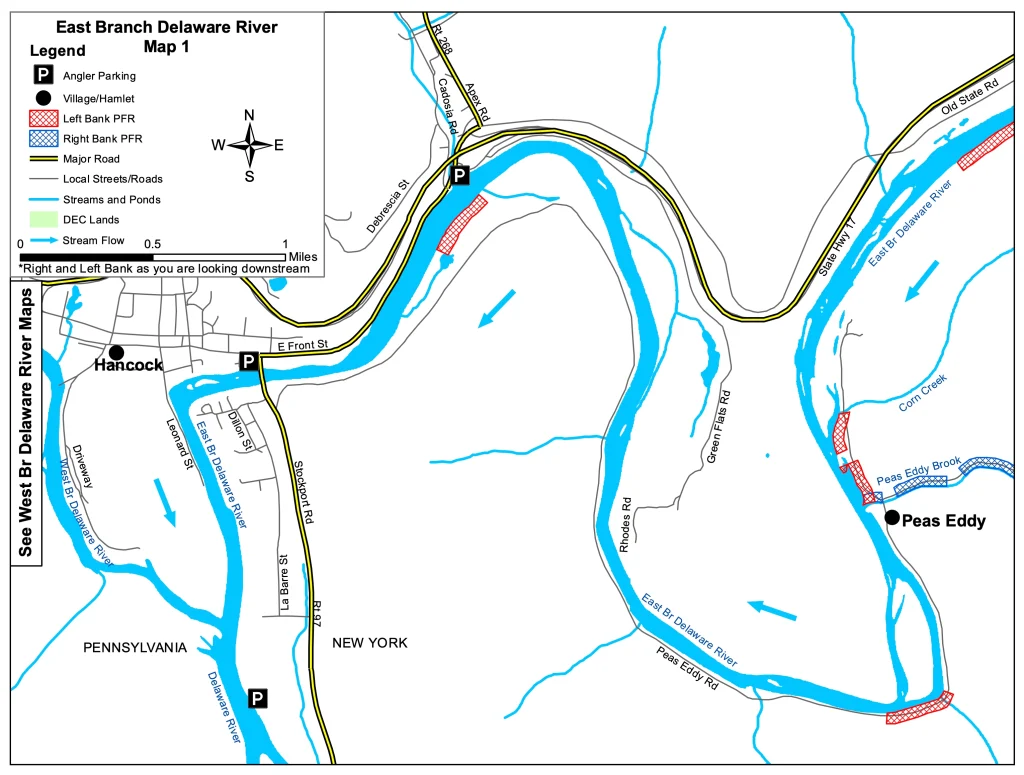

Anglers have a right to access the river from various New York State Department of Conservation boat-launch sites. Here’s a guide from the DEC. Toward the back (p.38) there’s a section called “Large Waters,” and that lists sites on the Delaware River as well as separately on the East and West Branches.

Peters says she has “no problem” with most of the people who fish near her land. She thinks kayaks and canoes are fine. She has a problem with people who anchor in the river adjacent to her property in order to fish. But, of course, that’s how you fish for trout: anchor the boat, stand up, cast.

She says that the people who anchor have no respect for how and when she wants to use her access to the river, and will yell at her from their boats, even crossing to “her side” of the river to berate her.

Ever since the creation of the New York City reservoirs, there has been a growing source of economic development in the Upper Delaware from trout fishing, since trout love cold clear water and the branches have, if the weather allows, an abundance of cold water.

But the best way to fish for trout — if you don’t own land by the side of the river — is by anchoring your boat and casting from it. A drift boat is usually used, with seats for one or two fly fishermen/women as well as a seat for the person manning the boat.

Some drift boats are launched from the riverbank by enthusiastic amateurs, but another way to fish for trout is to use a guide, who rents his or her services and a boat.

And this is where the argument gets heated.

Not all anglers are guides

The guides earn their living by knowing the river and where the best places are to find good fishing, which varies daily. These professional fishing guides are licensed to operate within the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River by the National Park Service. Guides also need licenses from NYSDEC for the East Branch and Delaware River and from the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission on the lower West Branch and on the main stem Delaware River.

Another wrinkle in the argument is that while the NPS licenses guides who fish in its waters, its waters don’t include the East and West Branches, since those waters are not in the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River.

Some of the landowners, Peters in particular, have a real beef with the fishing guides and accuse them of rude behavior.

Yet another wrinkle is how reluctant most of the people involved in this dispute are to talk about the problem. Some landowners were willing to talk but only off the record. None of the guides wanted to come forward, with both sides intimating that they were nervous about going public with their concerns.

Peters is the exception. She does paint with a broad brush and seems to identify everyone in a drift boat as a guide. But that creel survey by the DEC found that only 14 percent of the fishing traffic is from NPS-licensed fishing guides.

It may not have occurred to you, and certainly it won’t if you’re not familiar with the Friends of the Upper Delaware River, that the acronym of the Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation (RDUF) is the reverse of the Friends of the Upper Delaware River (FUDR.)

FUDR is often viewed as a sort of representative of the fishing guides and while it is true that FUDR was created to support trout fishing and has worked with communities in the region to improve fishing access and it is also the main voice in conversations with the New York City Department of Environmental Protection and DEC about the releases from their reservoirs, which is the supply of the cold clear water that trout need to thrive, it is not a representative of the guides.

Added to this boiling stew is some ancient history when fracking was still legal in New York State. The Peters family supported their right to frack and it seems to them that FUDR did not support fracking.

That’s another argument about who said what when.

Small communities do have a reputation for long memories.

DEC weighs in with guidance

But the whole argument is moot as of May 2025, when the DEC’s Office of General Counsel revised its policy that provides guidance on the issues of public rights of navigation and fishing on waterways in New York.

The revision rests on the issue of “navigability.” You can read all about it: OGC-9: Public Rights of Navigation and Fishing.

Summing up, the OGC said that public access is granted when the waters are deemed “navigable” by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Here’s an excerpt from a letter from Victoria Ruglis, a regional attorney with DEC Region 6 to Kathleen Bennett, a lawyer representing the Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation:

“For the lengths of the Delaware River, the East Branch of the Delaware River and the West Branch of the Delaware River that are consider navigable waters of the United States, the public has a right to navigate, fish, wade in the water, or walk along the banks up to the ordinary high-water mark, regardless of who owns the bed and banks or whether the waterway is posted against trespass.”

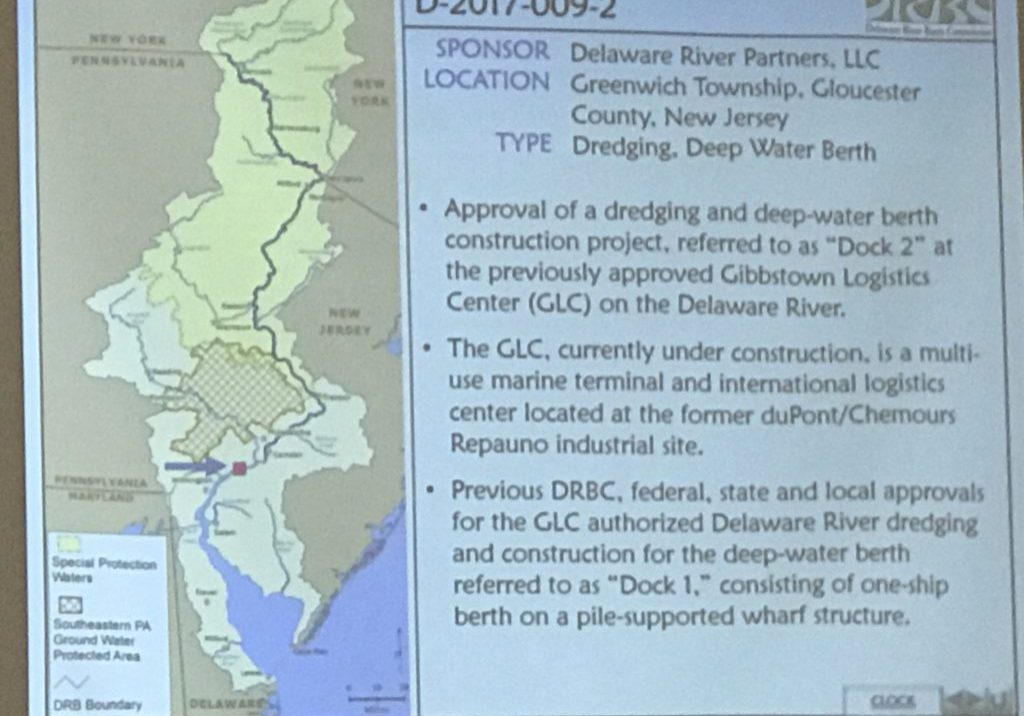

NYSDEC’s past policy has contributed to the confusion. Before this opinion, New York State did not adhere to the federal standards for access. As a result, there was much more limited fishing access. That’s why NYSDEC had a program called “Public Fishing Rights.” Through it, NYSDEC purchased access rights from landowners (maps here) which allowed fishing by the side of the river (up to 33 feet from the high-water mark,) and wading.

The downside of the program was its failure to insure anglers had access to those sites over land (since it was not a boating fishing-right program) and that meant the landowners would have had to agree to anglers parking their cars in a nearby roadside and walking on their land to where the site was. Perhaps, in light of the current turmoil, unlikely.

Here’s another wrinkle, years ago, a member of the Peters family sold Public Fishing Rights to some of its property on the East Branch near Peas Eddy Brook. Much of the property on both side of the West Branch near Peas Eddys is owned by members of the Peters family and by various Peters’ family businesses.

Here’s one of the maps from the link above which shows where these access rights were bought. The red hatchings near Peas Eddy Brook are on Peters land.

Now, of course, the new opinion essentially cancels the need for such a program.

Of course, the Riverland Defense and Unity Foundation could take the DEC to court and maybe get that policy overturned.

What is likely, though, is that the aggravation will continue, with both sides feeling harassed.

The search for peaceful co-existence

Ben Rinker, who is both a landowner and a fishing guide finds himself in a bit of a crisis of conscience, he said.

“As a guide, I like to know what’s around the next bend searching for an ideal place to fish. As a landowner and a businessman, I see heightened activity and increasing congestion.”

That congestion might be at the heart of this argument. As the upper river gets more widely known as a premier trout fishery, there are more and more anglers itching to try their hand. And the idyll of a peaceful day on a beautiful river all to yourself is getting less and less possible.

The Friends of the Upper Delaware River noticed the problem back in 2022, and developed an etiquette guide, which “offers river users suggestions to maximize enjoyment of this magnificent river system especially during the busy spring and summer season.”

FUDR’s executive director, Molly Oliver, expressed sympathy for both sides of the argument.

“While FUDR does not have a role in this decision,” she said, “we are acutely aware of the concerns and frustrations of both landowners and anglers. We continue to advocate for good etiquette on the river and hope to see this issue resolved in a way that respects everyone’s connection to it.”

In a complicated and increasingly popular destination, legalese won’t necessarily cool tempers, but some understanding of the different viewpoints might.