Improving water quality as a business: Why downstream users think it’s worth footing the bill

| September 15, 2025

In a perfect world, polluters would take responsibility for their impact on local waterways, whether that means taking measures to reduce their own pollution in their operations or partnering on clean-up efforts when mishaps occur.

In reality, that’s not typically how it works.

Even at a small, localized scale, water quality improvements on upstream properties can make a big difference to downstream users, like people in parts of northern Delaware who rely on waterways like White Clay Creek for drinking water. The trouble is finding the right funding source.

In parts of the Delaware River watershed some key players are embracing the idea of proactive partnerships to improve water quality and create a sustainable revolving fund.

This summer, some of those dollars have flowed upstream from the City of Newark to a property owned by Phillips Mushroom Farms in West Grove, Pa.

“We’re trying to prevent it at the source rather than remediate it further downstream,” explained Callan Dever, managing director of the Conservation Innovation Fund. “We know where the source is coming from. And it’s not in the state lines of Delaware.”

Heading off problems

It’s not the first time for this kind of interstate, public-private partnership on water quality improvements, nor is the idea unique to the watershed. The City of Newark has spearheaded a handful of similar projects since 2017, while the Nature Conservancy has been advocating for such localized water funds for years. Even New York City has set aside millions to support improvements on land in headwater areas of the watershed.

But at a time when funding and support for science are seemingly drying up, every little bit counts.

“We’re looking to attack the actual source of some of the pollution,” Dever said. “And also, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

How the funding works

In this instance, the City of Newark has once again partnered with an agricultural operation across state lines to improve downstream water quality — specifically, to reduce bacteria pollution from wastewater produced at the mushroom farm.

“We need to start thinking about the watershed as a whole and not just our small part of it,” said Kelley Dinsmore, an environmental coordinator with the City of Newark. The city relies on White Clay Creek to provide drinking water for its 30,000 residents. She said she hopes the project paves the way for others to embrace these innovative engineering and financing solutions.

An agricultural biofilter installed along fields used by a large, local business upstream may seem like a simple project to undertake, especially since it only took a matter of days to construct. But a $10,000 contribution from Newark literally added another layer to the $70,000 project. Thanks to that boost, the biofilter includes additional layers of biochar materials that are highly effective at trapping pollution that wouldn’t otherwise have been included in the design, in part because they’re more expensive than other standard materials like sand.

The biofilter Newark officials are backing is essentially a depression in the ground that includes layers of different materials to help filter pollutants. As the water percolates through, pollutants like bacteria get trapped in the layers, leaving the water much cleaner by the time it seeps through and reaches a pipe that leads to the nearby tributary of White Clay Creek.

Layers made of biochar, a mineral-rich material made from natural materials like wood chips that have been carbonized, are particularly effective at capturing pollutants found in runoff.

Finding solutions, not just pointing fingers

Getting finance, science and policy all on the same ground to support efforts like these has been years in the making, said Ashley Allen Jones, founder of i2 Capital and founding board chair of the nonprofit Conservation Innovation Fund.

The concept was simple: The Mid-Atlantic is still struggling with a water quality issue, mainly from “nonpoint” sources of pollution like runoff from roadways, fertilized lawns and farm lands. The major problem: paying for projects to clean up the pollution.

“Everyone kept saying there’s not enough money, we need 10 times the amount to solve this problem,” she said. “We really just gamed it out in a war room with white boards.”

That meant embracing known solutions, like onsite bioretention ponds that rely on vegetation to capture and store runoff, or other nature-inspired stormwater infrastructure, without just pointing fingers at some of those contributing sources — like runoff from agricultural operations — that are obviously also vital to the American economy and as a source of food.

“We have created some ecological challenges for ourselves,” Allen Jones said. “They’re real, they’re big, they’re pressing, they’re overwhelming. In the Mid-Atlantic in particular, water quality stands as the prime example of an externality we have not tackled.”

Forming partnerships

Figuring out how to incentivize practices that reduce pollution impacts from the start led the team at what’s now known as the Conservation Innovation Fund to home in on stormwater projects and related regulatory programs, like municipal stormwater system permitting requirements, which could be ripe for funding pitches.

The concept launched with about $1 million in pre-existing “angel capital” from i2 Capital followed by two conservation innovation grants from the USDA — each for nearly $1 million. In those first few years, another $750,000 from the William Penn Foundation, provided starting capital, Allen Jones explained, with additional support from the Agua Fund and the Dunn Family Charitable Foundation.

With those investments, Allen Jones said her team could start working with environmental and financial experts to develop both the business plans and administrative tools needed to support the science of qualitative models to calculate water quality impacts while also identifying the specific project needs within the Delaware River Watershed. That led to partnerships with the Stroud Water Research Center, the University of Delaware, the Nature Conservancy, regional stormwater experts, municipalities, corporations and more.

“We deal with farmers and private landowners to install BMPs on their land to clean up the runoff coming off of their land,” Dever explained. “And we quantify and package those pollutant reductions and sell them to municipalities.”

Some of the first projects took place in Kennett Township and aimed to reduce nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads by adding small-scale “best management practices,” such as a biofilter, onto farmlands in Chester County. The success of the approach isn’t just found in the water quality projects themselves, though.

“The idea is that ultimately we create a self-sustaining loop of funding,” Allen Jones explained. With contractual money coming from local, state and federal partners to incentivize local, private landowners to integrate practices required by regulators into their operations, the motivation for each to participate goes hand in hand: Regulatory requirements are met while the users on both ends benefit from financial support and environmental improvements.

Fighting an uphill battle

Dever noted that since a lot of municipalities lack the land space to install stormwater projects to improve water quality, working with farmers instead on smaller projects with big environmental impacts can help permit holders meet pollution reduction requirements in a more economical way. A contract between everyone involved ensures those targets are met, that the project is properly maintained and, in the meantime, the farmer also gets a small paycheck for participating by providing the land and upkeep, as is the case with the recently installed project at Phillips Mushroom Farms.

“Any kind of help is just great for us,” said John Rush, facilities manager at the 98-year-old business. Rush said Phillips has even been working on a treatment system to make the wastewater effluent drinkable.

“We do work very hard to try and do the right thing, to keep up with our BMPs and work to keep the water as clean as possible that’s going into the creek.”

That decade of work to get a revolving fund for projects in the Delaware River Basin finally paid off with the award of a $25 million grant from the USDA that would have supported dozens of projects like the one recently installed in West Grove.

Unfortunately, that funding is now frozen. It was part of the agency’s now-canceled Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities funding pool, which the Trump administration has called a “Biden-era climate slush fund.” The Conservation Innovation Fund has been invited to rework its application to meet new program requirements, Dever said in late June.

“It’s particularly tough because we’re coming out of a window of time when there’s been more funding available for many of these issues than there ever was before,” said Matt Ehrhart, the director of watershed restoration at the Stroud Water Research Center, noting billions in post-Covid funding through bills like the Inflation Reduction Act. “To see them not just tail off — but to actually see some of the clawback work that’s going on right now is challenging. And that’s not just happening for our work on the ground with farmers and other landowners, but it’s happening from a science perspective, too.”

But regional funding remains robust, he said. Dever said the fund has secured more than $15 million in new contracts with Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia for water quality improvement projects expected next year.

“And the work will continue,” Ehrhart said. “I think one of the most challenging pieces is when the funding dries up and the work completely stops and then the money starts again and you have to rebuild the whole system, including staff capacity and institutional knowledge.”

Outsized needs but small efforts help

Even if this idea of a revolving fund for the Delaware River survives the current federal climate, and if all the funding were still available, addressing all impairments plaguing the Delaware would be no small feat.

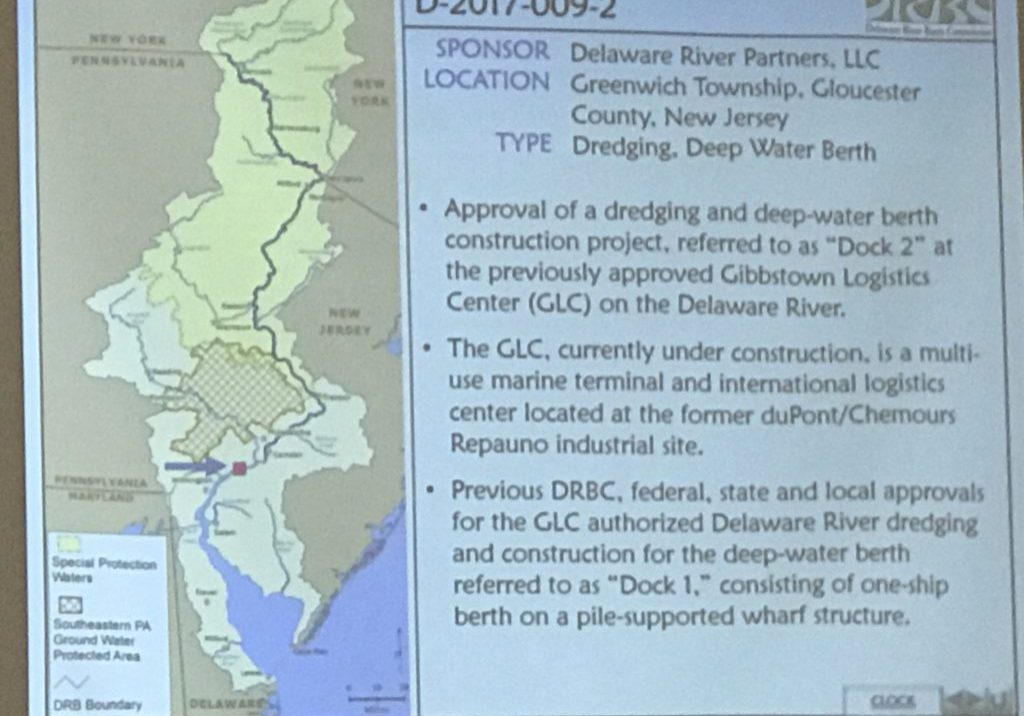

While nearly 15 million people depend on the Delaware River and its tributaries for their drinking water, a significant number of waterways also are considered impaired. Every two years the Delaware River Basin Commission has been charged by the Environmental Protection Agency to report on the river’s water quality, mostly measured against existing water quality standards. The Delaware River and Bay Water Quality Assessment for 2024 shows that many areas of the watershed are still affected by heavy metals and other pollutants, with many regions still under fish consumption advisories for legacy contaminants.

Still, even small projects like a biochar-enhanced biofilter can make big local impacts.

Biochar, which is great at absorbing microbes due in part to its porous nature, has been used in other stormwater projects throughout Delaware as well, including at the University of Delaware and in Dewey Beach. In those instances, officials touted that biochar could reduce nitrogen by up to 36 percent and even reduce the rate of stormwater flow.

“I think the states are seeing the value in those investments,” Ehrhart said of all the post-Covid funding that flowed before current funding freezes kicked in. “One of the hard parts of that right now is the remaining uncertainty.”