Delaware shipping sector warily watches for impact of Trump’s tariffs

| August 11, 2025

As President Trump draws and redraws a new global tariff scheme, the shipping sector along the Delaware River — a crucial economic driver for the region — is eyeing the process warily and waiting for the impact.

The president’s largest blow, a 125 percent tariff against China that he temporarily reduced, has been accompanied by a small drop in the weight of imports entering the United States through three of the most prominent ports that receive Chinese goods along the Delaware River: Philadelphia, Wilmington and Chester.

The weight of imported goods through the ports, most of which goes through the Port of Philadelphia, fell about 5 percent in the first five months of 2025, compared to the same period in 2024, according to U.S. Trade Census figures. The gross weight of seafaring vessels through the three ports fell from 29.4 million kilograms to 27.8 million kilograms, the figures show.

The number of vessels passing through the river dropped by about 2.5 percent in the January to June period this year compared to the same period in 2024, according to the Maritime Exchange for the Delaware River and Bay. The number dropped from 1,537 vessels in 2024, to 1,498 vessels in the same period in 2025, in contrast to a slight upward trend in recent years, the Maritime Exchange said.

While statistics alone don’t explain why trade has dropped slightly, the Maritime Exchange said no other events this year would explain the decline in vessel traffic. And logic would suggest it was prompted by concern over the tariffs, a top Maritime Exchange executive said.

“We do watch it very closely, and so I’m sure it’s got to be tariffs,” said the executive, who asked not to be named. “There’s nothing else much going on. What else could it be — uncertainty. And uncertainty is based on tariffs.”

The 150-year-old Maritime Exchange, a non-profit trade association, is the main advocate and information source for port and related businesses in the region.

Early days

There is otherwise scant evidence so far of the tariffs’ impact on commerce along the Delaware River. Shipping interests and related industries, which are nervously tracking their business sectors for fallout, say it is still too early to see, and assess, any impact. They think it could take several months for it to emerge in reduced import volumes, higher prices and a greater slowdown in import-related traffic along the river.

Tariffs are taxes that are paid by the importer or business bringing the goods into the United States, when the goods arrive here. Analysts say that the economic burden of the tariffs is passed on later in the supply chain, and is, in the end, generally shared among the importer, foreign companies that send the goods and eat part of the tax, and U.S. consumers, in the form of higher prices.

That, in turn, can affect a key engine to the local economy. The Port of Philadelphia, which accounts for the vast proportion of goods shipped on the river, handles about 7.5 million tons of cargo a year. The port supports about 18,000 jobs directly, and thousands more in the railroad, trucking, warehouse and other sectors, according to the port. It provides $25.4 billion in economic activity to the state economy,

according to the port.

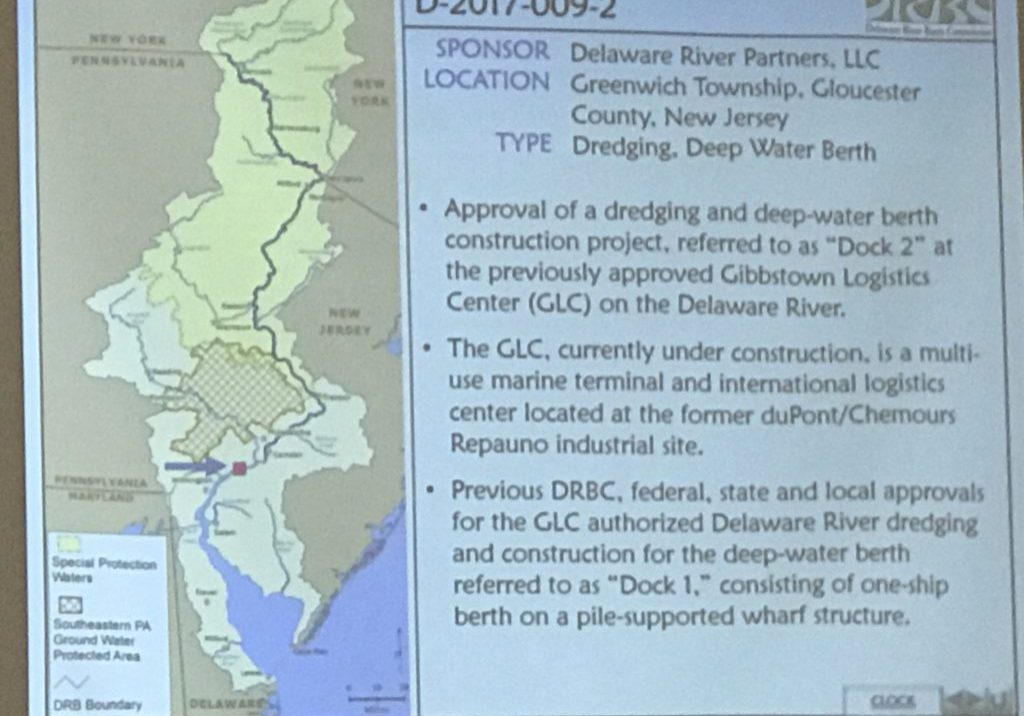

Read more: The Delaware River, already a major route for cargo, is poised to become even more competitive

Among the plethora of tariffs imposed by Trump, the 125 percent tax on U.S. imports from China — later reduced to about 30 percent pending talks — has been the biggest. Whatever the impact, China is not a big sender of goods up the Delaware, with imports accounting for less than 2 percent that pass through the Port of Philadelphia, which is also known as PhilaPort.

But Trump also placed a 10 percent tariff on imports from most of the rest of the world, with other additional tariffs for many countries. The combined impact could add up. That means the multitude of goods imported up the river — from cars made in Mexico, to refrigerated fresh fruit and vegetables that predominate in the rivers’ ports — could carry the related cost increases, pushing up prices and curbing demand so fewer imports move on the river.

The Maritime executive said it is not just the actual tariffs imposed, but the constant changing of the rules by Trump that worries executives at shipping, logistics and other companies.

Brazil, for example, is the top sender of imports through PhilaPort, accounting for 16 percent of all imports by weight, according to the port. Trump on July 9 threatened to impose a 50 percent tariff on imports from Brazil because of his dissatisfaction about a criminal case pursued by that country against former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, an ally of Trump’s.

Such a tariff would take time to filter through the growing, packing and logistics process that precedes its arrival in Philadelphia.

Nevertheless, the reaction to Trump’s tariff threat in Brazil — a major producer of orange juice concentrate, some of which ends up being delivered via the Delaware River — was swift.

“The very next day, the producers in Brazil were saying: ‘It’s very simple. We’re raising the price. And so, anticipate America that you’re going to be paying more for your orange juice,’” the Maritime Exchange executive said. “But what is that effect on the Delaware River and the percentage of imports? The trade picture hasn’t really changed. It’s just everybody’s waiting, and wanting to see what in God’s name is America doing next.”

When Trump first announced his across-the-board tariffs, there were signs of a small surge in cargo movement as shippers tried to get goods into the United States before the tariffs hit, he said. But that has dissipated.

“I don’t see a panic in the shipping industry,” the Maritime Exchange executive said, referring to the entire tariff picture. “Everybody is watching extremely closely, but everybody has a wait-and-see” attitude.

Handling more containers

At PhilaPort, spokesman Dominic O’Brien said the port has not yet seen much evidence of the impact of the tariffs.

“There are so many political, commercial, economic and weather factors that impact trade that it is hard to tell, especially given the varied and confusing nature of the tariffs,” he said.

Moreover, China, the country most affected by Trump’s tariffs, accounts for only 1.87 percent of the port’s imports by weight. The 10 countries that account for the most imports — and together account for about 75 percent of the ports imports by weight — have been hit with the relatively modest base level of 10 percent. Those significant importers include Australia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, New Zealand and Peru. Just outside the top is 10 Germany, which faces a 15 percent tariff in a deal struck by Trump with the European Union.

Read more: Delaware backs plan to quadruple trade capacity through Port Wilmington

The port’s vehicle imports through the 155-acre SouthPort Auto Terminal, one of the largest auto-processing facilities on the East Coast, may in the long term be significantly affected. The facility imports a significant number of cars from Mexico, which face a 15 percent to 25 percent tariff, depending on the share of components made in the United States.

Port Wilmington, on the Delaware side of the river, which is home to facilities operated by the Dole Fresh Fruit Company and Chiquita Fresh North America, also is watching closely for signs of an impact on its cargo volumes.

A May update report prepared by port operator Enstructure for the Diamond State Port Corp., which owns the port, said the company is “actively monitoring tariff developments,” including an assessment of the “anticipated impacts on cost, labor, storage space and other logistics factors.”

The report predicted a “low” expected impact on volumes of key commodities that move through the port, including: containerized perishables and consumer and manufacturing goods; breakbulk, such as pulp and steel; and bulk commodities, such as grain and salt.

Governor predicts uncertainty

Concern at Trump’s initial wave of tariff’s prompted Gov. Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania to visit the Port of Philadelphia in April. While there, he spoke to port leaders, businessmen and workers about the tariffs.

“Tariffs are taxes — and they’re going to make everything from fresh fruit to chocolate to auto parts more expensive for Pennsylvanians,” Shapiro said at the event, adding that 20 percent of the nation’s imported fruit comes through PhilaPort. “We are facing some serious economic uncertainty right now …. The chaos and uncertainty around these tariffs are going to cause companies to hold back, to keep capital in their pockets.”

Trump argues that his tariffs will help bring back manufacturing jobs to the state. Shapiro said Pennsylvania is also looking to revitalize the manufacturing sector, and bring those jobs back to the state, but he suggested that imports will always be important.

“There is only so much we can bring back,” he said. “We can’t grow bananas in Pennsylvania. They have got to come from somewhere. And those bananas that have been coming from Central America, now, for no reason, cost a whole lot more for consumers.”

Asked in July for an update on the impact, the Shapiro administration said some areas are already suffering.

The tariffs are “making it more difficult for our companies and industries to do business by making them less competitive in key markets and causing other countries to impose their own tariffs on Pennsylvania goods,” said Justin Backover, press secretary at the Department of Community and Economic Development.

He cited the example of the Volvo Group, which announced in April that it would lay off between 250 and 350 workers at its Mack trucks manufacturing facility in Macungie in the Lehigh Valley. The company cited the tariffs among other factors for the move.