Preaching to the choir: Draft State Development Plan comes to the NJ Highlands

| March 4, 2025

New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the United States with a seemingly unquenchable desire to develop, which can create a slew of environmental problems. Remember, what happens on land affects our water.

But a one-size-fits-all solution will not answer the needs of counties as diverse as urban Bergen in the northeast and rural Gloucester in the southwest. So “cross-acceptance” is the goal for New Jersey’s State Development and Redevelopment Plan, unveiled in December and the on-going mission for the Office of Planning Advocacy. (Here’s a story from NJ Spotlight, written when the draft plan was unveiled.)

Cross-acceptance is the term the plan uses to describe the negotiations that the state will be having with each county, or special area, to acknowledge the differing situations on the ground in each county. And that’s what happening now.

As of last week, meetings have been held in Cumberland, Mercer, Salem and Somerset Counties and one for the NJ Highlands Council region. There will be meetings held in every county in New Jersey. The dates, times and locations of the remaining meetings can be found here.

At the New Jersey Highlands Water Protection and Planning Council offices in Chester, the acting executive director of the Office of Planning Advocacy, Walter Lane, spoke about the plan to about 20 people and took questions.

It was a cordial exchange, with very little of what can be explosive set-tos from either side of the hot-button issue of development in the state.

Likely it’s because the Highlands have been involved in its own state-authorized planning conversation with residents and business interests for more than 20 years since it was set up by the New Jersey Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act in 2004. As much as 70 percent of the state’s residents get some or all of their drinking water from the Highlands, some as far away as Gloucester, through a complicated interconnection system.

And the plan doesn’t change much of what’s already set up in the Highlands region. “The Highlands Master Plan was dropped into the state plan,” said Benjamin L. Spinelli, the executive director of the New Jersey Highlands Water Protection and Planning Council.

Exploring what the Highlands are helps understand its relationship to the Delaware River and how it’s one of the foundations of the state’s drinking-water system. Another element to know about is the state’s dependence on Delaware River water via the Delaware and Raritan Canal.

Not a single watershed

The Highlands is a water-supply area, not a single watershed. In the Delaware watershed, we get our name from our mutual dependence on the Delaware River. In the Highlands there are several watersheds, ours, which is the Delaware, the Raritan, and the Passaic.

This hilly region is pockmarked with ponds, streams, rivers and reservoirs. The water distributed from much of those are under the control of the New Jersey Water Supply Authority, which runs the Spruce Run and Round Valley reservoirs. Another reservoir in the Highlands is the Wanaque Reservoir, run by the North Jersey District Water Supply Commission.

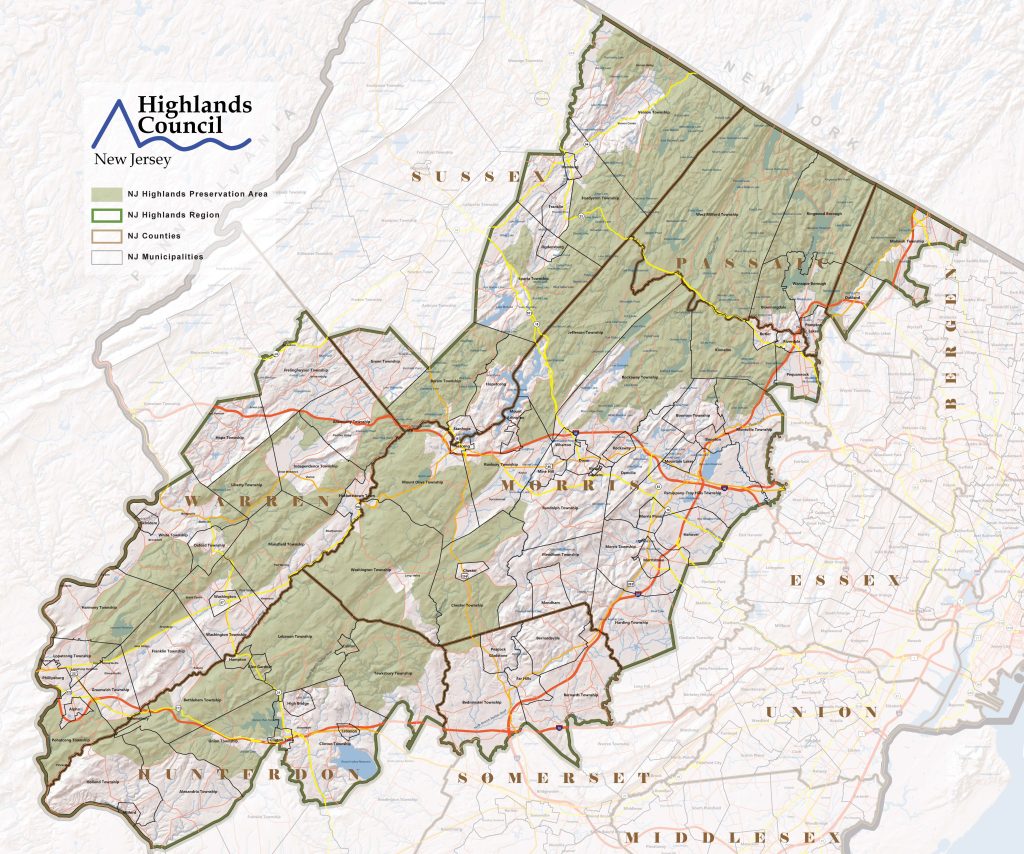

Most residents get their water from groundwater wells. The 15-member Highlands Council encompasses 88 municipalities in parts of seven counties, about 860,000 acres.

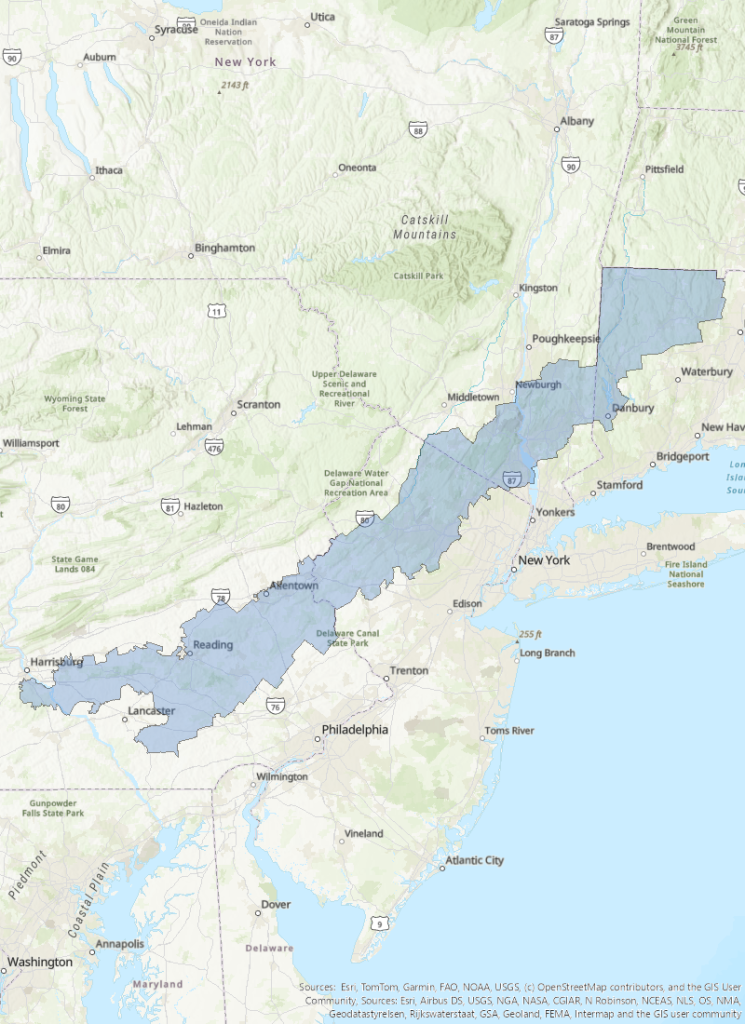

It’s also one of the more protected areas in a singular geographic formation that runs from deep in Pennsylvania through to Connecticut. The whole region has been called “the Highlands” since the 1700s. The legislative boundaries of the region were set by the Federal Highlands Conservation Act in 2004 from about Harrisburg, through 11 Pennsylvania counties, to the New Jersey Highlands, then through about five counties in southeast New York State, ending in three counties in Connecticut.

New Jersey took that ball and ran with it, understanding the region’s importance to its water supply. Work to protect that water supply was needed: In its weighty 2008 Master Plan, it notes that despite how clear most of those waterways look, more than half of the area is denoted with impaired water quality. (p.83)

In a macro sense, the region is divided largely between preservation and planning areas.

In the preservation area, conformance with the Regional Master Plan is required. In the planning area, alignment is voluntary. There are other layers (and layers) of development guidelines, called Land Use Capability Zones. Spinelli explained that this region was in development for both residential and industrial uses long before the Highlands Council existed and any sort of specialized land use was in effect.

It might help to understand the NJ Highlands to compare it to our neighbor to the north, the New York City reservoir system, Spinelli said. According to Spinelli, the New York reservoirs’ watershed is 2,000 square miles; the Highlands is 1,350.

New York reservoirs export 1.1 billion gallons a day; the Highlands exports 840 million. New York City reservoirs serve nine million people; the Highlands, seven million. The Highlands budget is $5 million; New York’s is $108 million. The Highlands is much more populous than the New York City watershed.

“That’s what makes what we do such a stunt!” Spinelli said. “But our nine million people were not sentenced to live in New Jersey. We want to keep New Jersey a terrific place to live.”

That means getting planning input from all stakeholders to find out what the state — and its people — really want, said Spinelli.

And that, according to Lane, from the Office of Planning Advocacy, means coordination among all levels of government.

There are, as outlined by Lane in his presentation, 10 goals for the plan: economic development; housing; infrastructure; revitalization and restructuring; climate change; comprehensive planning; equity; historic and scenic resources; natural and water resources and pollution and environmental clean-up.

“Lots of the goals are interconnected,” Lane said. And importantly, “We’re not generating mapping changes. Counties and municipalities will propose those.”

To date, Lane said: “The meetings have been very successful. There have been good discussions and we have received a wide range of public comments on the draft State Development and Redevelopment Plan.”

The hope of the New Jersey State Planning Commission as well as the Office of Planning Advocacy is to have all of the different phases of the plan completed by the end of 2025.

Comments can be sent to the State Planning Commission via an online survey or via email.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)