Upper Delaware River hazmat drill reveals shortcomings in responses

| October 21, 2024

A multi-agency drill on the Upper Delaware River last October that depicted the release of hazardous materials into the river arising from a train derailment revealed shortcomings in communications among emergency responders and a critical failure by a federal contractor, according to government records.

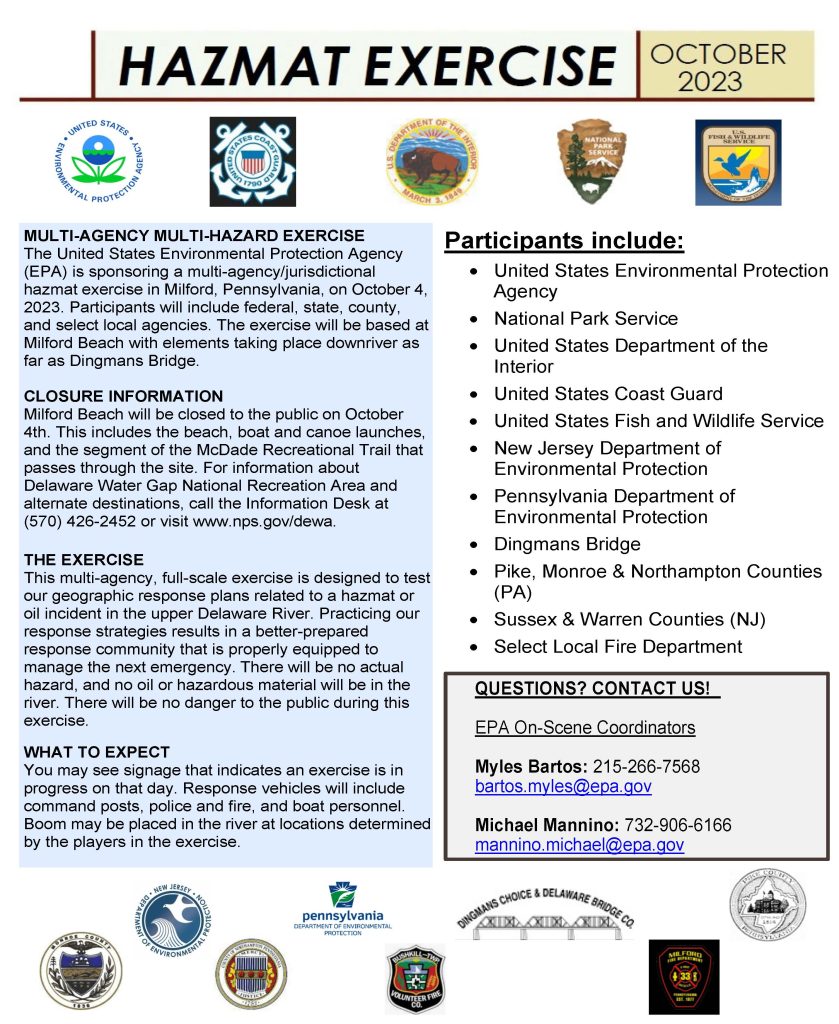

The exercise, involving more than a dozen federal, state, county and local agencies on the Pennsylvania and New Jersey sides of the river, took place along boat and canoe launches at Milford Beach in Pike County, Pa., on Oct. 3-4, 2023.

Agencies were put to the test responding to a nightmare scenario: A train carrying Bakken crude oil, chlorinated solvents and other materials, like soybeans, derails. Some train cars catch fire, oil is discharged into the river and hazardous substances are released into the air.

The mission: Deploy air-monitoring equipment and capture all of the oil in the river, which for purposes of the drill, were represented by rubber ducks.

But in the case of a federal emergency response contractor, things were far from ducky.

A ‘yikes’ moment

Myles Bartos, an on-scene coordinator and organizer of the drill from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, wrote a follow-up email to participants two days later. In the email, which surfaced in public records, he assessed how the exercise went.

In a moment he categorized as “yikes,” Bartos cited a “Grand Canyon-sized gap” in the ways the U.S. Coast Guard and a contractor for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency deployed booms — a floating barrier used to contain spills in waterways.

While the Coast Guard successfully deployed its booms, the contractor, identified by the EPA as Environmental Restoration, was “unable to successfully deploy booms,” according to a post-mortem on the exercise, known as an after-action report, that was finalized in July.

The emergency and rapid response services contractor “demonstrated inadequacies in experience, equipment, and technique while attempting” to deploy its boom and appropriate adjustments were not made, according to the report.

“If this setback occurred during an actual response, additional areas downstream could be impacted and subjected to contamination,” said the report, which recommended additional drills and unannounced exercises for the contractor. Representatives of Environmental Restoration could not be reached for comment.

Communications breakdowns

Communications among the players was cited as another issue.

“Not having clear communication upstream of the event made it more difficult to make decisions downstream,” the after-action report said. “Proper chain of command was not followed during all phases of the exercise, including while trying to get coordinates of the spill.”

Bartos described shortcomings in the drill’s design that led to chaos over predetermined roles during its early stages as one of the exercise’s “ugggghhhh moments” that led to confusion in the chain of command.

“A significant amount of time was spent discussing communication during the exercise and trying to get on the same page,” the report said. “The time it took communicating equated to less time acting out the exercise.”

Working among “sensitive” National Park Service areas

The report also found that the National Park Service needs a “clearer plan” for working in sensitive areas during a potential response. The drill in this case involved two Park Service units: the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area and the Upper Delaware Scenic & Recreational River.

“It could pose a negative impact and delay efforts during the response if the National Park Service were to have extensive internal discussions to weigh factors of impacted species/habitat and impacted human health and environment during the exercise/response, rather than having a plan in place prior for such situations,” the report noted.

The report cited the need to develop Geographic Response Plans, which Lindsey Kurnath, the superintendent of the Upper Delaware Scenic & Recreational River, described in an email to Delaware Currents as “site-specific strategies for the initial response to a spill of oil, oil products, or other hazardous materials on water.”

These plans provide guidelines for responders that can significantly reduce the time needed to make decisions in the early stages of an emergency, Kurnath said.

“A GRP provides the responders with essential information about the site, the equipment needed to carry out an effective response, access details and other information,” she said. “The goal of a GRP is to ensure that the response to a spill is fast and effective, and that sensitive areas and resources in them are protected.”

The report described the development of these plans as “extremely important,” noting that the response “resulted in an expanded area of contamination during the exercise and could pose a similar issue in a real emergency.”

“Response times are critical,” it added. A GRP “would allow for all personnel within the agency to have the same comprehensive understanding and to be able to properly provide direction on how to address the response as opposed to having a ‘direct order of steps’ for someone to pick up and run with during an emergency.”

Kurnath said that among the lessons learned from the drill is to have Geographic Response Plans “in place for any areas with sensitive species populations prior to implementing a spill response plan.”

Praise for honest feedback

In an email to Delaware Currents, a spokesman for the EPA, Shaun Eagan, described the training as “critical for the EPA Mid-Atlantic Region as it maintains strong relationships with its whole-of-government partners and improves our capabilities in protecting human health and the environment.”

He said the EPA did not have any further drills scheduled for the Delaware River in 2025, “but an exercise could develop at any point during the year.”

The report noted that, “despite challenges, the exercise provided valuable insights and opportunities for improvement in emergency response protocols.” It concluded, “Overall, the exercise was a success.”

In his follow-up email, Bartos described a “healthy” debate and “great conflict and even better results and learning opportunities” that came from the participants.

“All too often, people either keep quiet or present a world of pink unicorns and purple rainbows,” he wrote. “I like honesty. Thank you.”

He ended the email on an upbeat note, saying he hoped to talk and see the participants soon.

“But I hope it’s by choice, not catastrophe,” he wrote. “If it happens to be for catastrophe, I’m confident that’ll work out as well.”

How we did this story

The reporting for this article was drawn from records that came from Right to Know requests to Pike County, Pa., and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection; the after-action report provided by the EPA; and from a Freedom of Information Act request to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection denied a public records filing related to the drill, saying a request related to the drill for a particular set of dates was “overbroad.”

Northampton and Monroe Counties in Pennsylvania denied a records request, saying they had no records because they were not drill participants. However, the EPA confirmed that Northampton County participated in the full-scale exercise and Monroe County participated in a tabletop exercise.

And nearly a year later, Freedom of Information Act requests made to the U.S. Coast Guard and the National Park Service remaining outstanding.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)