EPA hearing focuses on new dissolved oxygen rules for section of Delaware River

| February 6, 2024

The tussle over revising the uses of the urban section of the Delaware River, as well as the accompanying water quality criteria, continues.

The first of two public hearings scheduled for those uses and criteria was held on Tuesday, the second on Wednesday.

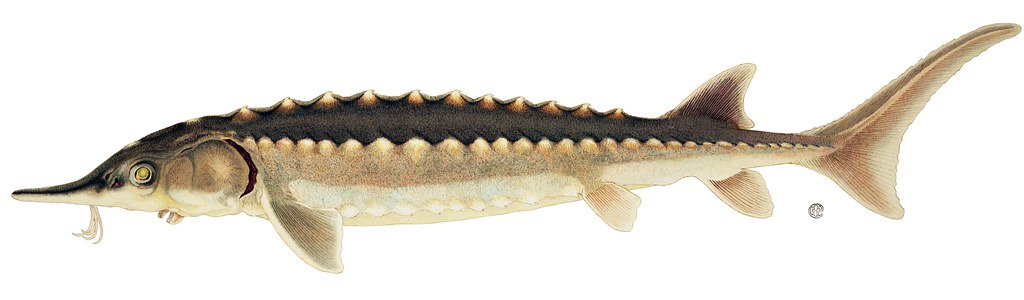

These hearings focus on an upgrade to dissolved oxygen criteria considered by many to be crucial to the continued survival of Atlantic sturgeon and the short-nosed sturgeon, which are federally endangered species.

The Environmental Protection Agency is holding these hearings, since the EPA stepped into the lead role for these proposals in December 2022. (Read more about those new criteria here.)

Since 2017, it was the Delaware River Basin Commission that was doing a deep dive on the science, engineering and financial impacts of any upgrade — an upgrade that was long overdue in the opinion held by many, as the perilous state of these fish has been (mostly) agreed on for many years.

Here are the uses and criteria the sturgeon are living with now:

The zones listed here are for the tidal Delaware River and Bay.

New rules aim to make the urban core more hospitable

Two elements are the targets: where propagation as well as maintenance is indicated as a designated use, and the 24-hour average DO criteria. In these urban waters, it’s less than in the rest of the river, creating what might be a wall of not-enough-oxygen to impede passage of sturgeon up or down the river.

The proposed rules make it all tad more complicated, but the bottom line, for supporters of the new rules, is that requirements for a new DO standard will make the urban core more hospitable for sturgeon and their young.

Those rules, however, will make it necessary for municipal wastewater treatment facilities in the 27 miles from Philadelphia, Pa., to Wilmington, Del., to spend a lot of money to improve their treatment systems, ensuring that there’s less untreated water going into the river, which creates the adverse dissolved oxygen condition that threatens the sturgeon.

At the same time, that work, though costly, will make those waters closer to the “fishable, swimmable standards” promulgated by the Clean Water Act. It might be a step toward allowing residents of these cities to use the river as freely as many communities both above and below the urban core, which would be a significant environmental justice win.

Costs are a contention

At the hearing on Tuesday, only five speakers presented, with most representing known points of view in the ongoing debate. On Wednesday’s hearing, there were probably 10.

On Tuesday, supporting the EPA proposed regulations but asking that the EPA take the DO standards even higher were Sharon Furlong of Bucks Environmental Action, Erik Silldorff, Restoration Director and senior scientist with the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, and Susan Voltz from the Clean Air Council.

Furlong acknowledged the financial impact to municipal wastewater facilities.

“Pitted against any of the arguments around cleaning up the Delaware and making it sufficiently habitable is the argument about cost,” she said. “The costs of cleanup, the costs of new facilities, the fueling and maintenance of those facilities, the need to revamp a discharge and piping system that is old in this very old and very poor set of towns, and the difficulties in how the population can absorb these costs. These are all important arguments; these are all important considerations.

“It is sad that the 15-year delay has exponentially raised these costs, but there you go. We cannot undo the additional financial burden of the passage of those 15 years. However, the costs and who pays is vital to these decisions and must be addressed, but again, we are talking about life and death for numerous living things, along with the fact that cleaning up the river that is the primary drinking source for over 15 million also directly benefits humans. A cleaner river, a better waste treatment system, less pee and poo flowing into the free-flowing water.”

Silldorff said the proposed standards “would not be fully protective of sturgeon.”

“The Delaware Riverkeeper Network supports EPA’s proposal to designate full Aquatic Life Use Protections for the entire tidal Delaware River. We support EPA’s scientific evaluation of the Dissolved Oxygen needs in the estuary, but we argue that this body of scientific information requires instantaneous minima, higher oxygen thresholds, and shorter assessment windows.”

Steve Tambini, executive director of the DRBC, indicated that progress, which is vital, needs to embrace all the river’s stakeholders so they welcome the new standards

“The DRBC supports adoption of revised water quality standards for the Delaware River Estuary,” Tambini said. “The EPA proposal reflects the shared goals of the federal Clean Water Act and the Delaware River Basin Compact. We encourage stakeholders to support the proposed designated use and the application of science-based water quality criteria to protect all stages of aquatic life.”

Philadelphia Water Department has its doubts

Jason Cruz, an environmental scientist from the Philadelphia Water Department, the largest wastewater treatment facility in the watershed that likely faces the biggest bill for upgrades, questioned the data that has been used by the EPA to develop the new standards.

He said, basically, that the PWD has determined through its own measurements that the population of sturgeon is not nearly as threatened as these proposals would suggest.

“Yogi Berra once said: ‘You’ve got to be very careful. If you don’t know where you’re going, you might not get there.’ I’d like to paraphrase Yogi by saying, ‘If you don’t look for something, you might not find it.’ Such is the case with Atlantic sturgeon in the Delaware River.”

So, he said, asking PWD ratepayers to foot the bill — ranging into the hundreds of dollars per ratepayer — is asking too much on the basis of science that the PWD disagrees with. (Read more about the PWD’s stand here.)

On Wednesday, Kelly Anderson, the director of PWD’s Office of Watersheds clearly stated PWD’s support of higher DO criteria, but not as high as the EPA has proposed, which are, she said, “higher than needed for fish propagation.”

More about PWD’s response to the proposed new rules here.

Also on Wednesday, Kelly Williams, the commissioner for the City of Wilmington’s Department of Public Works, gave a summary of the high-cost (in the millions of dollars) projects the city is facing, calling them unfunded mandates. She compared today’s demands to those of the Clean Water Act when it was first enacted — back then, money was made available for the work that needed to be done.

And, also speaking from the perspective of municipal wastewater treatment facilities, Charles Hurst, the director of DELCORA (Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority) regretted that the EPA hasn’t developed more community engagement on the possibility of higher costs leading to higher rates. He noted it was particularly important to engage environmental justice communities, which are often overlooked in matters of public policy.

Lastly, picking up on a Yogi Berra theme, Doug O’Malley, executive director of Environment New Jersey quoted him on Wednesday: “It gets late early here.” O’Malley noted that it’s getting late for sturgeon and other vulnerable species affected by low levels of dissolved oxygen.

You can send written comments online, identified by Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2023-0222. Find out more here.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)