What happened to a high-tech, leak-seeking underwater robotic vehicle for the NYCDEP?

| July 10, 2023

Note: This article has been updated with a fuller comment from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

When a homeowner has a leak, they call a plumber.

When the Pentagon has leaks, it sends out teams of investigators.

And when the New York City Department of Environmental Protection has leaks, it relies on smart underwater vehicles deployed in water tunnels.

For decades, the DEP has known about leaks in the Delaware Aqueduct that are leading to the loss of as much as 30 million gallons of water per day.

At a cost of $1 billion, fixing the 85-mile-long tunnel (the longest in the world) represents the largest and most complex repair project in the 180-year history of New York City’s municipal water supply system.

However, a former consultant involved with one of the high-tech devices that was to inspect the tunnel is raising questions about the DEP’s preparedness to do the work, which has now been postponed to October 2024 from this fall.

The former consultant, an undersea specialist, Michael Lombardi, said the DEP contracted for a $14 million state-of-the-art remotely operated vehicle known as the Chiton to inspect the leaking sections of the aqueduct prior to it being dewatered.

The problem, Lombardi asserts, is that the DEP took delivery of the device in 2018 but never put it into service.

That, he said, begs questions about what became of the Chiton, whether the DEP is relying on outdated data about the tunnel’s condition and whether there is an underexplored risk of it collapsing.

It was not immediately clear what happened to the Chiton or why it was mothballed.

Representatives from those companies most involved in the development and procurement of the Chiton — ASI Group, Arcadis and J.F. White Contracting Company — did not respond to requests for comment.

A DEP spokesman, John Milgrim, cited previous explorations of the tunnel.

“DEP will continue working with the top engineers and scientists in the field to obtain the most complete data available and make the most appropriate decisions possible to ensure the continued reliable delivery of the highest quality water for generations to come,” he said.

In a fuller statement in October in response to questions from Delaware Currents, he added:

“The Chiton ROV remains a complicated and untested apparatus and since 2014 has not been intended by DEP to be used as a routine tool for the Delaware Aqueduct repair project but only for potential emergency applications elsewhere in the water supply system.

“The manufacturer, which no longer exists, was ultimately unable to follow through with most of the contractual obligations, including testing and operational commitments. The ROV must be deployed and extracted through a riser valve which carries an untenable level of risk for an untested machine that’s no longer supported by the manufacturer. The Chiton hardware (received in 2018) remains in DEP warehouse inventory.

“At the same time, the upgraded autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) used by DEP can be reliably submerged, operated and extricated from the aqueduct and is expected to be used again before the October 2024 shutdown when the leaking section of the aqueduct is due to be bypassed and then plugged at each end of the leaking segment and decommissioned, not repaired.”

Moon-landing precision technology

Lombardi described the Chiton as among “the most sophisticated tunnel inspection systems ever conceived,” providing engineers with data about the locations of cracks or other tunnel defects “with extreme precision.”

“I worked on the later stages of the Chiton program, and can say with absolute certainty that the tool in NYCDEP’s toolbox represents the collective genius of the absolute best specialists in the undersea technology business,” he said.

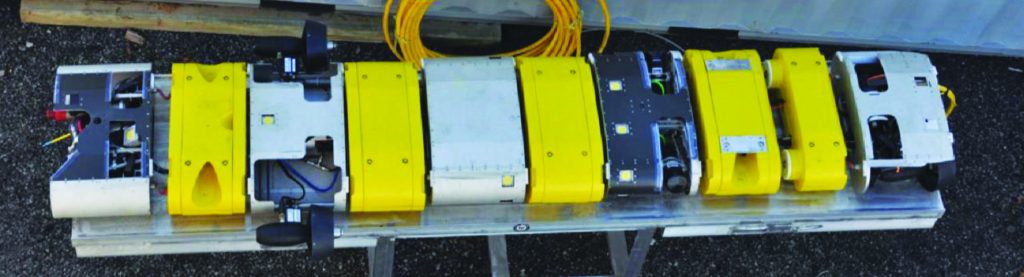

The 580-pound Chiton, which is made up of multiple rigid segments and resembles a series of power adapters connected together, got its name from the chiton, a segmented mollusk. Lombardi said it was a one-of-kind vehicle, purpose-built to get around a particularly tight space in a shaft that was deemed the best spot to inspect the leaky tunnel.

“In addition to the robotic vehicle itself, the complexity of insertion and extraction via a restriction at Shaft 5a and then traversing over three miles to the target area requires precision akin to landing on the moon,” he said.

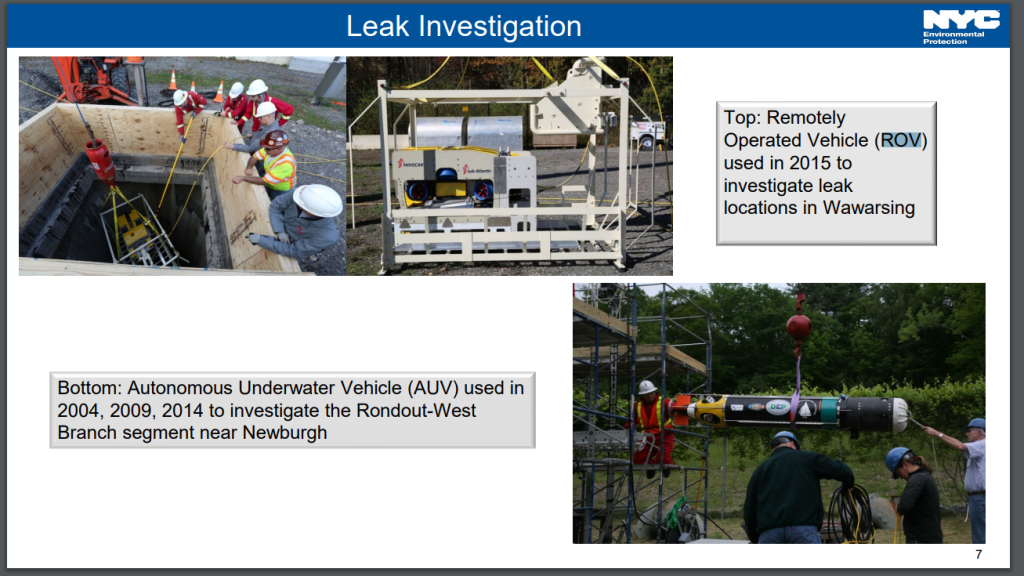

Previous explorations of the tunnel relied on so-called “smart torpedoes” — autonomous underwater vehicles used in 2002, 2003, 2009 and 2014 to investigate the Rondout-West Branch segment near Newburgh, N.Y., and a separate remotely operated vehicle in the aqueduct under Wawarsing, N.Y., in 2015, according to the DEP.

Those vehicles used “flight pattern” technology that allowed data to be analyzed only after the fact, Lombardi said. Remotely operated vehicles like the Chiton are tethered to the surface, can send multiple live video streams in high definition and allow for real-time data analysis, Lombardi said.

Had the Chiton been used as planned, it could have provided an improved risk assessment about the potential for a tunnel collapse, he said.

The construction of a bypass, working around the leaky sections of the tunnel, was substantially completed in 2021 though it is not yet tied into the old aqueduct. Lombardi pointed out that to make the tie-in, the leaky section will have to be dewatered, and therein lies the hazard.

“While dewatering, hydrostatic pressure will be lost,” he said in an email. “To plug the tunnel, this compromised section will have to be accessed by workers (dry), which is incredibly risky.”

Another issue is potential water ingress as the work will be taking place under the Hudson River. Lombardi said a “material breach of the tunnel could leave underground voids with unknown long-term environmental consequences.” And, if for some reason a significant collapse happened near the tie-ins, it’s possible the DEP might not be able to bring the system back into service, he said.

“How does the DEP expect to complete this tie-in, and do they have sufficient data about the structural integrity of the leaky sections to do this safely?” he asked.

Longstanding collapse concerns

Concerns about a potential tunnel collapse date back more than 20 years.

A report in 2000 from the environmental watchdog group Riverkeeper, which at the time was headed by Robert Kennedy Jr., warned that it may already be too late to shut off the water and repair the leaks in the tunnel.

“City engineers are so concerned that they will not turn off the water because they believe there is a strong possibility if the water is turned off the entire aqueduct will collapse,” Kennedy said, The Times Herald-Record reported at the time. “The damage may be so great that the aqueduct is held together only by the internal pressure of the water.”

Geoffrey Ryan, then a DEP spokesman, disputed the findings.

“Could the aqueduct collapse?” he said. “It’s conceivable. But anything is conceivable. Nobody thinks there is a likelihood of that happening.”

Read more: NYCDEP recovers from fumbled community outreach about Delaware Aqueduct shutdown

A 2007 audit by the New York State Comptroller’s Office said the DEP’s 2003 inspection using an automated underwater vehicle found a 7,000-linear-foot section of the tunnel that was heavily cracked. Most of the cracks were found in two areas of the tunnel near geological faults, the report said.

At the time, the report cited an unnamed consultant that in 2004 found the risk of a collapse or major puncture was “much higher than what is preferred considering the catastrophic nature of a tunnel failure.”

“This consultant reported that the risk is 0.1 to 1 percent, which is at least 10 times larger than the preferred range of less than .01 percent,” the report said at the time.

Lombardi said the Chiton could have provided the DEP with more up-to-date data.

“The conditions certainly have not improved themselves since then, and therefore the tunnel failure risk is certainly much higher” than what was found in the 2004 analysis, he said.

Victoria Leung, a staff attorney at Riverkeeper, which issued another assessment of the leaks in 2009, said the group had heard from Lombardi and passed along his concerns to the DEP at a meeting last fall.

The DEP expressed satisfaction that sufficient investigation had been done to account for any potential tunnel collapse, she said, and that the risk had diminished based on modeling it had done.

“I definitely think there is grounding in his concerns,” she said of Lombardi, adding that Riverkeeper lacked the engineering and technical expertise to assess the DEP’s models.

The aqueduct is one part of a larger system that delivers about 1.1 billion gallons a day to New York City and four counties north of the city.

Changes in plans for repairs

In June 2022, the DEP paused the planned aqueduct fix for a year, saying it needed more time to prepare for the monthslong closure. In a series of public meetings this spring, DEP representatives said they would make a go/no-go decision as the shutdown, planned for October, drew closer.

However, the DEP announced last month that it was delaying the shutdown until October 2024. That is the result of new findings from the temporary shutdown completed in March.

“Data collected during that timeframe revealed that seepage from groundwater aquifers was infiltrating the aqueduct deep underground at more substantial rates than originally anticipated,” Milgrim said.

Instead of the full shutdown that had been planned for the fall, the DEP will now conduct a dewatering test for a longer duration than what was done in March, he said.

“This will facilitate the collection of even more detailed data to better understand the groundwater infiltration rates,” Milgrim added. “This shift is necessary to allow for additional dewatering pumps, related drainage infrastructure, and augmented electrical support to be installed and constructed to keep the work area in the city water tunnel dry during the complex repair.”

Meg McGuire contributed reporting.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)

Need more info on what might happen to water supplies if, in fact, there is a failure that shuts the thing down …

Contrary to the DEP comment, AUV inspections are unlikely to provide the resolution required for the interrogation, hence the ROV being commissioned. The manufacturer of the system is still very much in business.