More variables than constants in NYC shutdown of Delaware Aqueduct

| May 6, 2023

If you’ve attended any of the sessions where the New York City Department of Environmental Protection explained its plans for the Delaware Aqueduct shutdown on Oct. 1 (this is the third), you know these slides and the plan pretty well.

On Thursday, Jennifer Garigliano — who’s just had a promotion from chief of staff at the Bureau of Water Supply to director of Water Resources Management — again reviewed slides and answered questions from Upper Delaware Council members as well as from the public at the UDC offices in Narrowsburg, N.Y.

What became interesting this time were the questions, and not because there was any hostility, but the questions showed just how complicated this piece of the water-supply puzzle is.

Different people want different things from the river. If the river had never been dammed, people would have to settle for whatever the river offered: flood or drought and all stages in-between.

Once we can alter what the river offers, then it’s a bit of a tussle among interested parties.

Although there were no anglers present, we have heard often enough that one of the big draws to bring anglers (and their much-needed economic support) to the Upper Delaware is trout fishing and trout are finicky. The trout fishing has improved remarkably since the construction of the dams that allow a steady supply of cold clear water, which is ideal for trout.

So, those anglers and the various businesses that hope to keep afloat from anglers, would likely support as much cold-water releases from those dams as possible, which is an underlying promise for this summer. Most summers there’s less of that cold water as the weather gets hot and New York City is conserving the water for its primary purpose — supplying water.

Concerns over too much water

Then, we heard from a previously unheard source of concern: the livery companies. Those are the companies that rent out canoes, kayaks or rafts.

Many of those become authorized by the National Park Service as commercial use permit holders. Those permits have some safety parameters that include not being able to boat when the river gets too high.

And that was news to Garigliano.

Even though it’s taken 20 years to finalize plans for this $1 billion project, there can still be surprises (a good reason to hold multiple presentations to get the word out).

The projected releases might be high to get those reservoirs close to 30 percent empty by the time of the shutdown on Oct.1, but now, Garigliano said, she would take the concerns of the livery companies into account as the DEP develops its release plans.

The livery companies’ concern — too much water — was a bit of a contrast to the concerns of Diane Tharp, executive director of the North Delaware River Watershed Conservancy.

She’s been a longtime advocate for the reservoirs to have a constant void to allow them to mitigate downriver floods, instead of, in her view, contributing to them.

That is an argument that she’s been putting forth for many years and her voice is at least one reason that the NYCDEP does maintain a 15 percent void for much of the year, which ends in April.

According to both the NYCDEP and the Delaware River Basin Commission, the reservoirs by their enormous size already attenuate the threat of flooding. Many disagree, including Tharp.

From Tharp’s vantage point, NYCDEP should be aiming to keep that 30 percent void not just at the beginning of the shutdown, but throughout the five to eight months of the shutdown, which would mean more water coming down the river — but she theorized, less flooding. Then a month before the aqueduct is to be turned back on, then the reservoirs should be allowed to refill.

Garigliano has, in these presentations, stopped short of being alarmist, but is clearly concerned that New York City will have enough water from the reservoirs left in the system by the time the project is completed.

Even more concerning is what is the water supply likely to be if the project does indeed reach the outer limit in the five-to-eight-month forecast for completion.

Garigliano wants to be able to start filling up the Delaware reservoirs as soon as possible to allow them to take over from the rest of the system, many of which will be very nearly drained dry.

Quite a nerve-wracking prospect.

The role of the FFMP

But Tharp is also concerned that planning for this project did not put enough weight into the effects of climate change that we’re feeling in the increasingly wet Delaware River Basin, which is a fairly recent phenomenon.

The NYCDEP says it reviewed climate data from the past 63 years, since the dams were built. But Tharp’s concerns are from the past 10 years.

Underpinning much of Tharp’s concerns was the Flexible Flow Management Agreement. That’s the agreement among the four states in the watershed and New York City about how much water will be released in an attempt to ensure that there’s less swinging from too-much to too-little water.

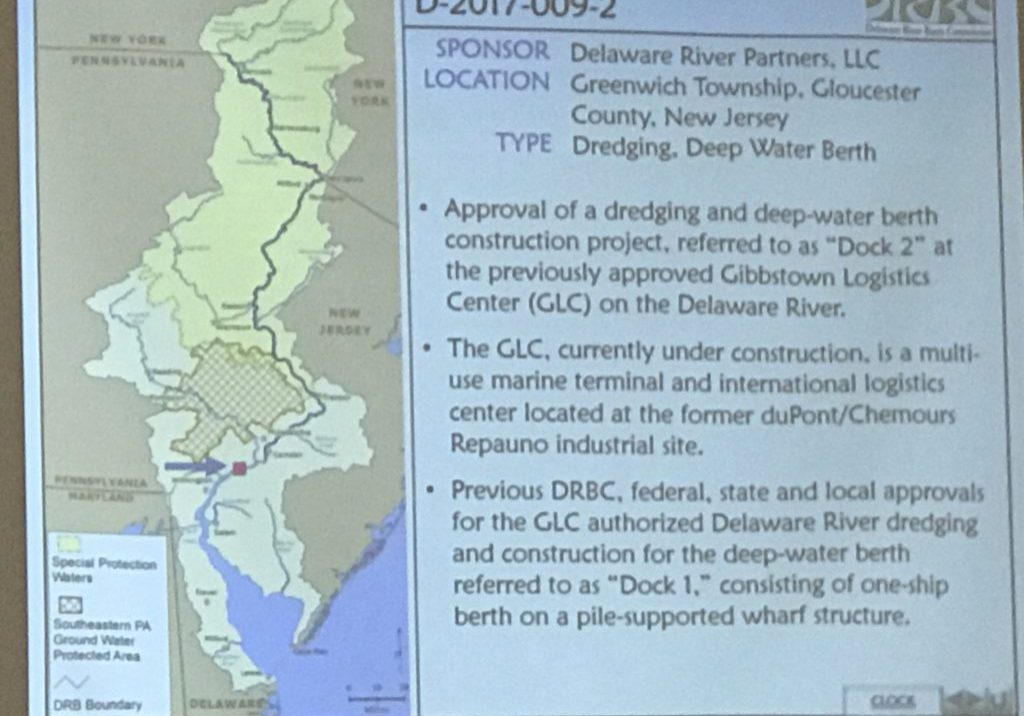

It’s a complicated document and subject of seemingly endless discussions. The last time the FFMP was agreed to in 2017, it nearly ended in stalemate as New Jersey was concerned if there would be enough water for its needs in the releases from the reservoirs.

Some of Tharp’s concerns echoed those of Joan Homovich, who spoke at a meeting in Hancock, N.Y., last month.

Homovich lives below the Pepacton Reservoir and is a longtime advocate for people who live below the dams. She is, like Tharp, someone who has experienced flooding first hand.

They are both experts in the complicated procedures of the FFMP, but insist that we cannot rely on the usual FFMP releases because they will not be aggressive enough, but instead need maximum releases.

At that Hancock meeting, Garigliano said that the FFMP will not be the sole guide for releases. And, she said, the releases might vary considerably from that guide. If the reservoirs are judged to be “too full” for this period of time, there will be additional releases.

Garigliano has stressed, repeatedly, that much of the decision making has to be done in real time, with due consideration to all the variables.

“There do seem to be more variables than constants,” concluded the UDC chairman, Aaron Robinson, who represents the Town of Shohola.

NYCDEP is planning an ongoing series of meetings through the shutdown and beyond. The next one, with the DRBC, is either in-person at the West Trenton Volunteer Fire Company or live streamed. Check out here for more details.

You can check out the same data that the Delaware River Master uses to see what’s happening on the river and above it here.

And if you want to really dig in on the data, from the same folks (USGS,) the FFMP 2017.