Upper Delaware basin is cursed and blessed

Pristine streams are a plus but draw little notice from Pa. officials

| June 15, 2022

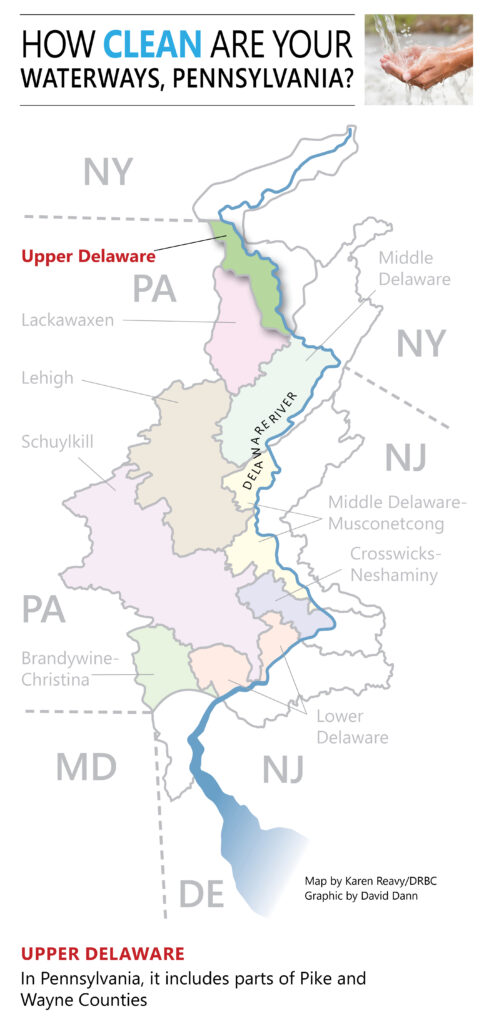

Editor’s note: This is the latest in a series of stories exploring water quality in the nine basins in Pennsylvania that are part of the larger Delaware River watershed. How clean are your waterways, Pennsylvania?

Compared with the eight other Delaware River basins in Pennsylvania, the Upper Delaware basin in the Poconos comes out the second best in water quality, according to a recent state report.

The Upper Delaware in Pennsylvania, which includes parts of Wayne and Pike Counties but also stretches into New York, had a mere 63 miles listed as being impaired for fish consumption. The other categories the report measured – for aquatic life, potable water and recreational uses – awarded the basin zeroes, which in this case, is a perfect score. The lower the number of impaired stream miles, the better.

Only the Lackawaxen basin, with a paltry five miles found to be impaired, came out better.

Laurie Ramie, executive director of the Upper Delaware Council, said she was pleased to see that Wayne County had among the lowest percentages of impaired streams (4.8 percent or 71 miles out of 1,453 assessed miles).

She attributed that strong showing to a “relative lack of development and more abundant open space.”

She said Pike County had a “more concerning” rate of 24 percent of its stream miles rated as impaired (240 out of 977 miles) but said it was “not astronomically high.”

As the waters in Pike and Wayne Counties are perceived as clean, they are also therefore seen as in less need of attention and assessment, said Jeff Skelding, executive director of the Friends of the Upper Delaware River, which is known as the FUDR.

That curse and blessing cuts both ways, he said. “If you don’t assess the stream, how do you know about the conditions of the stream?” he asked.

Indeed, the 2022 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection report did not assess or reassess the streams in the Upper Delaware basin at all. The most recent data from past assessments was carried forward for summary statistics about the basin in the 2022 report, a DEP spokeswoman said.

“The state agencies are like everybody else – they’ve got tight budgets,” Skelding said. “They go to where the problems and the politics are.”

For the state lawmakers in Harrisburg, Pa., and Albany, N.Y., the Upper Delaware is comparatively a “lost little section of the State of New York, the State of Pennsylvania,” he said.

“There is an assumption that we are rural and that there’s nothing going on,” he said. “We don’t get the love from Harrisburg that we’d like to get.”

That, in turn makes securing funding for work on the basin a challenge, with more troubled areas garnering more money.

Legacy uses leave lasting changes

The Upper Delaware basin is not entirely unblemished.

Unlike basins in urban and suburban areas, which tend to have more problems with sewage and runoff, the Upper Delaware is coping with changes from industrial uses of more than a century ago, such as grist mills and tanneries, which rechanneled the water to serve their particular needs.

Those modifications caused erosion in the tributaries, which in turn, promote sedimentation that is harmful to aquatic life, Skelding said.

“Our tributaries are unraveling,” he said. “They’re not stable.” Simply put, he said, “There’s too much dirt in the streams.”

Speaking in general about the DEP water quality report, Robert Walter, professor of geoscience at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa., and co-director of the Chesapeake Watershed Initiative, said the impairments cited were not unusual “given the trajectory of change that Pennsylvania has gone through.”

Industrial users of old led the construction of dams and other redirections of streams to harness their power, which changed the dynamics of waterways and completely changed the hydrology of some places.

“We’re beginning to understand the legacy of this impact goes back a long, long time,” he said. The actions of our ancestors have unwittingly contributed to the problems of today, he said.

While that’s true, Skelding added that “it’s not to say that we’re not doing things that will aggravate the situation,” such as building subdivisions that have not been well thought out, parking lots and megastores like Walmart.

“Rivers change all the time,” he said. “What we did is made changes faster and more unnaturally.”

Add climate change to the mix, with its more frequent and intense rainstorms, and the problems get exacerbated.

“It goes from a twinkling little brook to a roaring, flooding stream,” he said. He described the effects as “screwing around with the natural formation of our waterways.”

Added to all that is the attractiveness of the Upper Delaware as a rural area and a renowned trout fishing spot within a day’s drive of major metropolitan areas such as Boston and New York City.

That has led to an influx of visitors, particularly during the pandemic, prompting the FUDR to promote ways for outsiders and locals to peacefully co-exist and cooperate. (See an April 3, 2022, Delaware Currents story “How to share a slice of heaven.”)

“With Covid, they could come here, and they did come here,” Skelding said. “We want to love the river but we don’t want to love it to death.”

Michael Mele contributed reporting.