A bottomless problem: acid mine drainage in the Schuylkill Basin

Innovative solutions and funding sought to improve water quality

| June 8, 2022

Editor’s note: This is the latest in a series of stories exploring water quality in the nine basins in Pennsylvania that are part of the larger Delaware River watershed. How clean are your waterways, Pennsylvania?

Go for a drive with Bill Reichert and he will take you along an unpaved, rutted road just outside New Philadelphia, Pa., that jostles you like a carnival ride inside his big, fire-engine-red pickup truck.

With its overgrown weeds and occasional discarded junk on its side, the road seems like a path to nowhere but Reichert, who is president of the Schuylkill Headwaters Association, drives slowly and knowingly.

For him, the road leads to a very purposeful end: a project designed to reduce high concentrations of iron, aluminum and manganese that drains from an abandoned mine into Silver Creek.

In the interconnected veins-and-arteries world that is water, Silver Creek is a tributary to the upper Schuylkill River, which is a part of the Schuylkill River, which is the largest tributary to the Delaware River and part of the larger Delaware River basin in Pennsylvania.

So, what happens in Silver Creek ultimately influences the water quality of the Delaware, a river that is the source of drinking water to more than 15 million people, a huge natural habitat to hundreds of fish and birds, an enormous economic engine for goods and services, and a recreational refuge for anglers, swimmers and paddlers.

Reichert pulls up to the first of several ponds that make up what is formally known as the Silver Creek Mine Tunnel Discharge Project. As water leeching from the mine passes through successive ponds, metals drop out, and then flows through two wetlands before re-entering Silver Creek.

The project is designed to cleanse 1,200 gallons of water per minute, removing as much as 171 pounds of iron per day and raising the alkalinity of what is discharged.

The ponds sport a decidedly orange-red hue like the landscape of Mars. A clump of clay scooped from the bottom of a pond has the consistency of a thick cake batter, albeit one you would not want to eat. But that squishy mass is a signal that the passive treatment system (no pumps or electricity are used) is doing its job.

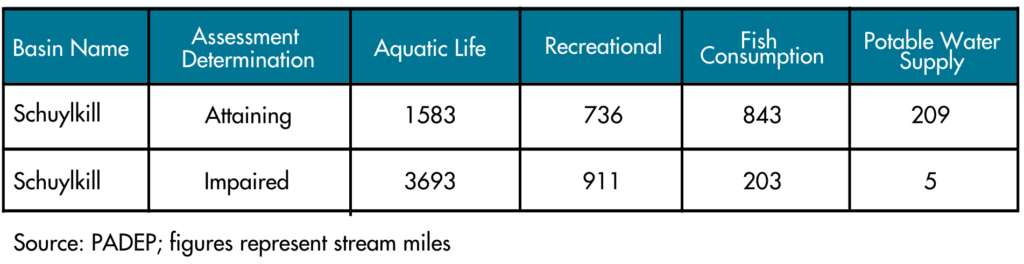

Nearly two-thirds of the streams in the Schuylkill Basin that were assessed for a 2022 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection report were found to be so polluted – or “impaired” in the official jargon – that they did not meet at least one of four standards outlined in the federal Clean Water Act.

The Schuylkill basin, which takes in parts of Berks, Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Lancaster, Lebanon, Montgomery, Philadelphia and Schuylkill Counties, is heavily dotted with industrial uses, most notable among them, former coal mining operations. Water fills the mines, producing acid mine drainage.

Pyrite, so-called fool’s gold, in the veins of the mines comes in contact with oxygen and oxidizes into a powder that readily dissolves in water, reducing its pH and turning it a rusty orange color.

The reduction in pH, in turn, allows metals like aluminum, cobalt and manganese to become more soluble in water, which allows small amounts of those metals to get picked up in the water.

Reichert said some streams can look “drop-dead gorgeous” but that the emphasis in that description is on “dead” because, as he noted, “Aluminum will kill everything.”

‘Subway tunnels filled with water’

Bobby Hughes, executive director of the Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation, said water never really shuts off in the mines because it seeps through via ground or rainwater.

Remediation treatments can be expensive and long-lasting, he said. Assessing the costs for treatment is challenging and varies from site to site, depending on flows and the chemistry of a given mine.

“When you look at these systems and take them on, they have to have funding that will last in perpetuity,” Hughes said. “It’s difficult to get ahead without constant attention.”

That’s an assessment shared by Reichert, who said the projects can be never-ending: “Once you get something cleaned up, you’re ready to move on to the next one.”

Wayne Lehman, a natural resources specialist at the Schuylkill County Conservation District, said strides have been made since the Clean Water Act and mine reclamation rules went into place.

Still, there are voids in mines that bring a risk of further water quality harm, he said. Beams are set to hold up the rock on the roof and sides of a mine tunnel but once they rot, the tunnel will eventually give way.

“When that rock collapses from the roof, it opens up new amounts of pyrite to the oxygen and flowing water in the mine tunnel where it was otherwise ‘sealed’ behind that rock before it collapsed away,” Lehman said.

How much of the metals and other materials in the abandoned mines remain that could be scoured and seep into the basin remains unclear.

Lehman said it amounted to “miles upon miles upon miles upon miles that are down there.”

“Imagine subway tunnels filled with water,” he added. “To go from where they are to totally clean – is that six years, 60 years, 60,000 years, six million?”

Data can be deceiving

The DEP report found that nearly 3,700 miles of streams in the Schuylkill Basin were impaired for aquatic life, 911 miles for recreational uses, 203 for fish consumption and five miles for potable water.

Notably,156 miles of streams that were once considered “attaining” – or getting passing water quality grades – were downgraded to “impaired,” the report found.

The underlying sources of the basin’s troubles reads like a pollution stew: coal mining, acid mine drainage, urban runoff/storm sewers, habitat modification, agriculture and removal of riparian vegetation, among others.

Despite the harsh assessment, experts in the basin said the findings were not unexpected.

Brian Rademaekers, the public information officer for the Philadelphia Water Department, said the increased number of assessed stream miles and their locations shaped the report’s findings.

“While earlier years of this assessment program focused on stream segments in forested watersheds where streams have more natural protections — such as riparian buffers and tree canopies — the 2022 report assessed more stream miles in developed watersheds subjected to human stressors,” he said.

Generally, he said, “point sources” – specific pinpointed sources of contamination, such as a leaking sewer pipe — pose a lower barrier to fixing in comparison to “nonpoint sources,” such as urban stormwater runoff and agricultural impacts, which are “diffuse and complicated.”

“These pollutions sources cross city, county and state lines. Solutions to these problems are often systematic — a change in regulations, behaviors or the type of infrastructure we build,” Rademaekers said.

Cause for hope

At the headwaters of the basin, Reichert said what impairments have been found were related to better testing and reporting.

“For us, it’s our history with the industrial age and the anthracite mining,” he said. “It occurred many years ago before there was any thought about the environment or pollution.”

Most of the basin now is connected to sewage treatment or septic systems, but it was not always that way. “When communities were built, there was no thought to stormwater runoff,” he said.

Lehman said that things are better compared to the state of the Schuylkill River from decades ago. Back then, industrial waste, sewage and coal mining discharges were deposited directly into the river with no treatment.

Still, there is much work to be done, Lehman said.

“Obviously, it’s not that bad, but it’s not where we want it to be,” he said. If, for instance, you reduce pollutants by one-third or half but you double the population, then the human impact on water quality means “you’re still fighting a losing battle,” he said.

Michael Mele contributed reporting.