Facts vs. opinion on the F.E. Walter Dam study

Editorial Report

| April 6, 2021

Editor’s note: The Francis E. Walter Dam Reevaluation Study is being conducted by the operators of the dam — the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — and two co-sponsors, the Delaware River Basin Commission and New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection, which will pay half the cost of the $2.6 million study. The purpose, according to the USACE, is to see whether, in addition to its primary missions of flood control and recreation, there are other alternatives to “optimize project operations.” Consideration will be given to water supply and water quality to identify possible improvements to its existing structure, infrastructure and operations that will support current and future demands within the region.

Almost from the start, anxiety from residents near the Lehigh River heightened tensions and suspicions about what the REAL motivations were for the reevaluation.

Have you heard the parable about the blind men and the elephant?

It came to mind as I listened to the testimony at the March 18 Policy Committee hearing on the Francis E. Walter Dam Reevaluation Study, and also statements made at the hearing and in testimony submitted.

The parable tells of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and each man finds a part of the animal and describes it subjectively according to his own experience. In some telling, the men come to blows because the other men’s experiences don’t mesh with theirs.

Rep. Doyle Heffley (R-Carbon County) requested the hearing and Rep. Martin Causer (R-Cameron and McKean counties) chaired the hearing.

The problem here is not just with some of the opinions presented as facts, but also with the complexity of the water system that includes the F.E. Walter Dam.

As the project manager of the study representing the United States Army Corps of Engineers at the hearing, Dr. Dan Hughes, said: “It’s a complex system that F.E. Walter is part of.”

The USACE operates the dam and, as Hughes said repeatedly throughout the meeting, the USACE is in charge of the water behind the dam and that’s not going to change.

But that’s not Kathy Henderson’s opinion. She’s the director of economic development for Carbon County. She said, “Since New York City is heavily invested in studying the feasibility of acquiring Pennsylvania water, our concern is that the study may lean in their favor. If New York gains control of the water behind the dam, recreation and other businesses that operate on or near the Lehigh River will be negatively affected.”

“..acquiring Pennsylvania water.” No. It’s her opinion and she’s entitled to it, but this is not any part of the plan, according to New York City or the USACE.

And further, she said that “New York’s ownership of 15% of F.E. Walter water storage capacity would effectively remove storage opportunities and limit the water that can be drawn.”

No ownership, as stated by the USACE and by NYCDEP.

The concern about New York “owning” 15% of the water behind the dam is an opinion echoed by all three of the Carbon County Commissioners, who submitted written testimony.

Chris L. Lukesevich: We stand united against New York City’s intent to sequester 15% of water held by Frances E. Walter.

Rocky Ahner: As a Carbon County Commissioner, I’m writing this letter with my opposition to the proposed Francis E. Walter Dam project to supply water to New York.

Again, not right: USACE’s Hughes said several times, this project has “nothing to do with supplying drinking water to New York.”

The Chairman of the Carbon County Commissioners, Wayne E. Nothstein, supported the opinion that New York was aiming to get that 15%, and added a new note:

“If New York City starts removing 15% of its water from the Francis E. Walter Dam during a drought, there will be nothing left downstream.”

It seemed to be forgotten by many speakers (and writers) that drought is the central issue here. That droughts do happen and when they do, the releases from the dam change, even before this study.

Hughes explained that there have been about 13 times since the dam was built in the 1960s when the USACE has restricted water releases. It follows its own USACE strict water code already in place.

Hughes said that the person in charge of the dam, USACE Lt. Colonel David Parks, “Controls the water and follows his own chain of command all the way up — it ends in the president’s office.”

As climate change begins to take effect, we are told by scientists based in local universities like the University of Pennsylvania and Rutgers University that the impact in the Delaware River Basin will be more water when there’s rain, and less when there isn’t. In other words, more flooding and more drought.

I imagine that many of the people who are alarmed by this reevaluation study would be equally alarmed if there was no advance planning in our region for increased flooding or more serious droughts. That’s what this is — and F.E. Walter will be one of many other sites examined in the future for what their roles might be in times of severe drought.

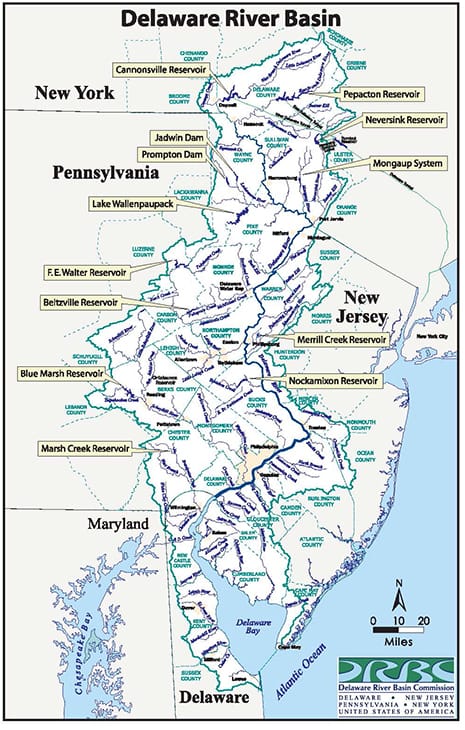

Have a look at the maze of reservoirs that all contribute to the water management of the Delaware Basin:

And here’s what that looks like on a map:

And like it or not, the four states of the basin have delegated responsibility for managing Delaware River waters to the Delaware River Basin Commission. Lots more detail about the DRBC’s interest in this study and in the Lehigh in the written testimony submitted by the DRBC’s Deputy Executive Director Kristen Bowman Kavanagh, here.

Rep. Jonathan Fritz (R- Susquehanne/Wayne counties) told the committee that “Our biggest adversary is misinformation.” Which is certainly true, but then went on to give his opinion — that he is suspicious of the DRBC.

“I will contend very seriously that you’ve got a partner here that lacks objectivity and I want to sound that alarm. It’s the Delaware River Basin Commission. They have been infiltrated by people that very much have an agenda. They are overzealous environmentalists and their goal is to shut down industry.”

But the commission isn’t its staff — and the staff is largely scientists and engineers. The commission has only five members: the governors of the four basin states and a representative of the federal government, the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The staff work on projects as directed by the governors and the USACE. Each member has one vote.

Heffley questioned the DRBC’s motives in pursuing this study;

“The DRBC has not been kind to residents in the Marcellus shale region and has blocked millions — if not billions — of economic development and taken land rights away from residents and not working with them so that is a concern.

“We see a pattern.”

Rep. Eric Nelson (R-Westmoreland County) concurred, addressing one of the speakers, Kathy Henderson:

“I know this is frustrating because I’m a big economic development person for Pennsylvania (Westmoreland County is near Pittsburgh.)

“This is also a negative impact for economic development of your region — the state of New York won’t allow or accept more Pennsylvania gas to help build economic development on our border.

“They want to take your water but they’re not allowing your gas.”

Suspicions abound

The other target of suspicion was the other sponsor of the study, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

Another complication: New York City was not one of the signers of the document that created the DRBC and is not one of its members. Only New York State is.

It’s important to note, as far back as 1931, the U.S. Supreme Court has issued decisions affecting how New York City uses Delaware River headwaters. Eventually, the court made New York City reservoirs responsible for a certain flow target at Montague, New Jersey. (That’s up in the northeast corner of Pennsylvania.)

The court case was brought by New Jersey, nervous that all the reservoirs being built would mean that New York State would rob New Jersey of the waters that its communities needed.

So the flow target was the Supreme Court’s way of ensuring New Jersey had the water it needed.

At the same time, that stipulation also insured that there would be enough downriver flow to repel the salt front. Or at least it was. To further insure that the salt front wouldn’t climb to Philadelphia’s water intakes, the DRBC instituted its own flow mandate down at Trenton.

The amount of water in the river has been a subject of intense review and study for a long time.

And climate change will change what has worked so far. Not only will there be — at times of drought — less water coming from upriver, there will likely be more salt water coming from the ocean as water levels in the oceans rise. And with no dams on the main stem, that impact could be felt even farther up river, beyond Philadelphia.

Salt is a serious issue: If the salt water from the Atlantic gets into Philadelphia’s water supply, it would corrode its pipes and would hamper that city’s ability to deliver drinking water to its residents. It would also be a blow to all the various industries that use Delaware River water.

A reminder: That means Pennsylvania’s water in the F.E. Walter Dam could be used to repel the salt front and ensure other Pennsylvania residents get adequate clean drinking water.

Many were of the opinion that New York City should fix its own water problems, and here’s Henderson again:

“New York City should take responsibility in upgrading their own water systems before relying on other states to come to their aid.

“Sacrificing Pennsylvania’s control over Pennsylvania’s water will jeopardize economic development opportunities in the Commonwealth for generations to come.”

No, and no. The control remains with the USACE, as Hughes said repeatedly.

That was echoed by Jennifer Garigliano, chief of staff, New York City Department of Environmental Protection: (This is from her written testimony, which is reprinted at the end of this article.)

“New York City is not interested in drinking water from F.E. Walter Dam, we are not interested in renting storage space at the reservoir and we are not interested in changing the recreation releases from the reservoir or its mission to protect the Lehigh Valley against floods.”

The New York City Bureau of Water Supply has been reducing waste in its system and has been actively encouraging its users to reduce water use, which is evident in the increased amounts of water in its system. In the past 10 years, NYCDEP has moved away from a relatively simple “fill and spill” policy towards its reservoirs. It works with a host of national and state agencies to develop dynamic models that get closer to predicting what amount of water the city needs, how much rain is in the foreseeable future and what it can use to increase releases to benefit, for example, the trout fishing in the Upper Delaware, a financial bonus for the economically strapped region.

The salt front

Yes, suspicions abound. Sky Fogel, who owns Pocono Whitewater Rafting in Jim Thorpe, Pa., wants a “written guarantee that there will be no changes in the current releases.” But, as explained several times by the USACE’s Hughes, there are already changes in the releases written in the USACE’s code for operating the dam when there are droughts.

More from Fogel: “One of the sponsors of this study is the New York City water authority, and its specific objectives are never mentioned. They would not have paid a million dollars in cash if they feel they couldn’t get something out of it.”

And there is. New York City doesn’t want to be solely responsible for the salt line — 200 miles away — at a time of drought when there’s a chance that its own water supply will be low. Those billions of gallons spilled during a drought to fight a salt front five to six days away would mean billions of gallons less that New York City has for its customers.

In a drought, the last thing any of the many water resource managers in the Delaware River Basin want to do is waste water.

The DRBC and NYCDEP keep a close eye on how much water is in those reservoirs, providing a daily update. As here.

It gives you the daily totals of storage in all three New York City reservoirs in the Delaware system: Cannonsville, Pepacton and Neversink.

You can also see where the various drought warning lines are. Once those lines are crossed, the DRBC has to take action to preserve as much water as possible and has the authority to declare a drought for the river — though not for any of the states.

In order to relieve New York City of some of the responsibility for that salt front, all of the players in that U.S. Supreme Court settlement have to agree. That’s the four basin states and not the USACE but NYCDEP.

Another party in the discussions is the United States Geological Survey Delaware River Master. The office was created by the U.S. Supreme Court and he, or she, makes the call about how much reservoir water needs to be released to meet the gauge at Montague.

Here’s a story about the role of the River Master and the all-important gage.

It has also been working with the parties in the Supreme Court decree and many Upper Delaware River conservation interests to figure out ways to increase the supply of cold water released from the dam to bolster the thriving cold-water fisheries that have become a strong part of the economy for Sullivan and Delaware counties in New York.

There’s a complicated management plan for this work called the Flexible Flow Management Program that has been the subject of many meetings between the anglers, and New York City, some quite contentious — much like the management plan that stakeholders have worked out with F.E. Walter Dam releases and the USACE.

More about that here.

I would say that the people from the upper river who have tangled with New York City’s Bureau of Water Supply might speak to concerns expressed by some.

I reached out to Jeff Skelding, the executive director of the Friends of the Upper River, who have been at the forefront of this work, to get his opinion based on his experiences with NYCDEP:

“Given the long history of NYC’s ability to manage the waters of the Delaware in a way that more often than not favors their interests (and sometimes to the detriment of downstream needs), it’s always a good idea to keep a close eye on them.

“However, it’s also fair to say that the City has become increasingly sensitive to downstream needs. Watershed stakeholders, both in the tailwaters and in the Lehigh Valley, might better spend their energy looking for win-win opportunities out of the F.E. Walter study.”

Now, do you see what I mean when I said that the problem is not that each of the individuals’ subjective experience is wrong — it’s just that there’s a huge puzzle that will need to be solved before droughts become a regular part of our water landscape.

Funding shortfalls

Fritz continued expressing his worries about the DRBC: “… and they may say that it’s just Representative Fritz’s opinion but if you want to do your homework, look at their list of funders. Look who’s funding the Delaware River Basin Commission. These groups, these agencies are non-government and they have a very clear mission of shutting down industry. I’m sounding the alarm that it’s hard to have an objective, innocent study when you have people that have this clear and dangerous objective.”

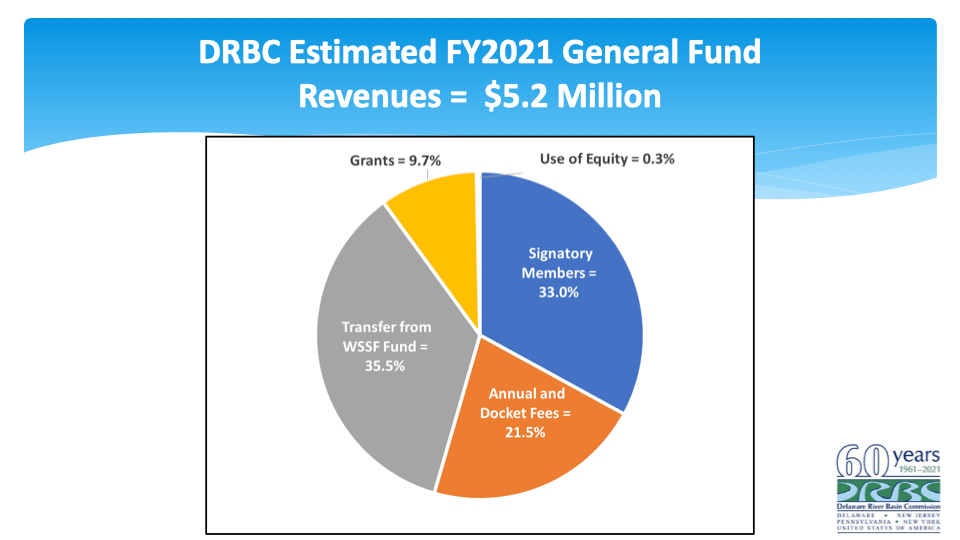

OK, here’s the homework.

This shows where the DRBC’s budget comes from. Its biggest source of funding is in the bucket labelled “Signatory members.” Those are the states and federal government. More on that in a minute. The other bucket is the Water Supply Storage Facilities Fund, in this graphic, we’re looking at the General Fund, and it shows the transfer of money from the WSSF, which is money collected from surface water users. Those charges provide the revenue stream for the DRBC, in turn, to pay the USACE for its water supply storage in two multi-purpose federal reservoirs, Beltzville and Blue Marsh. (I did tell you that this is complicated!)

Even though the WSSF Fund looks like a large bucket, the various costs associated with it diminishes its size.

Back to the signatory members. I have written many stories about the fact that the states and the federal government have not kept up their promised funding levels,

see here:

But it is clear that, even without that needed funding, one of the biggest sources of revenue for the DRBC is the money from those states.

Way down the list — at about 10% (and that’s the total of ALL grants) — are the grants that DRBC will get from various agencies to do work, and remember that work is as dictated by the four governors and the USACE. These are not grants proposed by the various organizations that are the funding sources. And yes, some of those are, to Rep. Fritz’s point, tilted toward environmental activism. But if Fritz tells us to do our homework. Here it is: Those grants are a drop in the bucket.

There’s another wrinkle in all this: The states routinely do not give what they agreed to give to fund the DRBC, especially Pennsylvania. Often, it’s the Republican-controlled Legislature that reduces the governor’s requested amount.

I suggest that if Pennsylvania and the other states (and the federal government) were to fully keep their promises, there would be far less need for the DRBC to go to those other sources that Fritz has a problem with.

Have a look at the very sad record of the states’ and federal government’s promised contributions to the DRBC:

What’s next

One of the likely outcomes — and it seems to be what both NYC and DRBC are looking for — is that there could be structural modifications to the dam to allow it to hold more water.

That extra water would come in handy for immediate downstream users of the Lehigh as it would be used during drought conditions to pour more water into the river, which would allow for the various recreational uses that are so important to the region.

This “more water” won’t be used to increase the water levels above current standards — so there’s no increased danger of water overfilling the river. Though we do have to give thought to the other effect of climate change: floods. And that is the primary function of F.E. Walter Dam.

That “more water” stored behind the dam would add to the waters repelling the salt front and help other Pennsylvanians get water to drink or to use in industrial processes. And, F.E. Walter won’t be the only dam that addressed salinity in the lower river.

“No,” said Hughes, “it will be a combined effort. We will need to go facility by facility to see what that combined effort will be.”

When there is a draft study, the USACE has promised stakeholders’ meetings and, if possible, during Covid, an in-person public hearing. If an in-person meeting isn’t possible (Covid) there will be a Zoom meeting. That’s where the proposals will be laid out in black and white.

In fact, though many speakers were grateful for this hearing, even this hearing is premature. There are no proposals, only opinions, theories and misinformation.

Most representatives questioned the people giving testimony about whether they were a part of this stage of the study — and most answered than they weren’t. But, this stage is all about water science and engineering studies.

What this ended up being was a way for Republican legislators to grandstand, provide political theater and create an echo chamber of doubt, suspicions and misinformation.

So, I’d recommend keeping a close eye on the proceedings of the study. Have a look at the draft report and attend whatever public hearings there are to stay up-to-date with the study’s findings, to discuss your specific, legitimate and subjective concerns.

When you have concerns try and take them to the USACE, which seems to have a good track record of trust from local residents. Politicians have a tendency to find heat and share that.

But heat doesn’t mean light. Don’t just share rumors with people who have a similar experience with the elephant and don’t get angry when others’ views of that elephant differ from yours.

Here’s how to contact USACE:

Comments are accepted on an ongoing basis throughout the study process. Comments may be submitted via email or in writing:

By email: PDPA-NAP@usace.army.mil

In writing:

USACE Philadelphia District

Planning Division

100 Penn Square E.

Philadelphia, PA 19107

As promised here’s the entire text from Jennifer Garigliano, chief of staff, New York City Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Water Supply:

Testimony by New York City Department of Environmental Protection Testimony given by Jennifer Garigliano, Chief of Staff, NYC DEP Bureau of Water Supply Pennsylvania House Republican Policy Committee

March 18, 2021

Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you for inviting me to speak about the ongoing study of the Francis E. Walter Reservoir, for which New York City DEP is a co-sponsor. My name is Jennifer Garigliano, and I am the chief of staff for DEP’s Bureau of Water Supply.

Our bureau is responsible for the operation, maintenance and protection of New York City’s water supply, which is the largest municipal water supply in the United States. Our 19 reservoirs provide water to more than 9 million people, including New York City and roughly 72 communities north of the city.

As you might know, New York City has long been involved in the development of flow policies and programs for the Delaware River – a responsibility that began in 1931 when the U.S. Supreme Court first affirmed the city’s right to draw drinking water from the headwaters of the river. The city owns and operates three reservoirs on the headwaters of the Delaware River – those being Cannonsville, Pepacton and Neversink reservoirs. Those reservoirs are part of our Delaware System, which provides about 50 percent of New York City’s drinking water. Those reservoirs also created and sustain a thriving trout fishery on the Upper Delaware River, and our releases of water from those reservoirs make up a substantial portion of the flow in the river, especially during droughts.

New York City’s involvement in the study of F.E. Walter Reservoir has been the source of considerable interest and skepticism over the past year. So I’d like to start my testimony today by assuring the committee, on the record, that New York City is not interested in drinking water from F.E. Walter Reservoir, we are not interested in renting storage space at the reservoir, we are not interested in controlling its operations in any way, and we are not interested in changing the recreation releases from the reservoir or its mission to protect the Lehigh Valley against floods. We recognize the indispensable role the reservoir plays in public safety, recreation, tourism, and commerce in this region, and we do not seek to interfere with any of that.

In fact, New York City DEP supported a precondition of the Army Corps study that said any changes to reservoir operations cannot affect the downstream releases that support the tourism and outdoor recreation economies in Pennsylvania.

Our interest in this study is very narrow and specific. This study is meant to assess potential changes at F.E. Walter Reservoir that could protect communities along the lower Delaware River and its estuary during severe droughts in the future. As climate change persists and ocean levels continue to rise, we know that salt water from the Atlantic Ocean will push farther north into the Delaware River. During droughts, scientists expect the concentration of salt in the river to rise

above the limits that are considered safe for drinking water. That saltier water would also pose a harm to the freshwater ecosystems of the lower river and the bay.

Currently, New York City’s reservoirs on the headwaters of the Delaware, which are located about 200 miles to the north of this salt front, bear much of the responsibility for pushing that saltwater back toward the ocean during severe droughts. This would be done by opening large valves at our reservoirs and sending billions of gallons of water into the river at a time when those reservoirs are severely depleted. The travel time from our reservoirs to the lower river is approximately five to six days.

Recent modeling indicates that fighting the salt front with New York City’s reservoirs alone is not an effective or efficient use of water. To be clear, we do not believe that water from our reservoirs alone will be enough to push the salt front back during the longest, most severe droughts that we can expect in the future.

That’s why a group of scientists and river managers agreed several years ago to pursue this study, which was ultimately authorized by Congress. All of us wanted to understand whether other reservoirs in the basin could also contribute water to the river during those most dire droughts, when the health of our ecosystems and the viability of water supplies in all the basin states are in danger.

During those discussions, a fresh look at F.E. Walter Reservoir emerged as a top priority. Because F.E. Walter Reservoir is closer to the salt front, its waters could supplement releases from other reservoirs – including those owned by New York City – to help push saltwater back toward the ocean more efficiently and effectively.

That is the central question of this study. In simple terms, river managers and stakeholders want to understand: Can F.E. Walter Reservoir pitch in to protect the lower Delaware River during severe droughts?

This type of analysis for F.E. Walter Reservoir has been contemplated since the severe drought of the 1960s, which was the drought of record for many parts of the region. After that drought and the drought of the 1980s, the basin states and New York City signed something known as the “Good Faith Agreement,” in which they agreed to examine options to fight droughts in the future. The potential use of water from F.E. Walter Reservoir to support and protect the lower basin was at the top of that list in the 1980s – and here we are today actually putting science behind that idea.

Importantly, I want to stress that this study is an honest one. The Army Corps of Engineers is studying a range of structural and non-structural options, which the committee heard about this morning from the Corps. The outcome of those analyses will be based on sound science, and not the desires of New York City or any other party. The study is accounting for the needs of all stakeholder groups, including people who live in and around the floodplains below the dam, those who rely on the reservoir for tourism, recreation and commerce, and communities that might benefit from additional protection during future droughts.

Along the way, we believe the study is likely to find simple ways to enhance the benefits that people in the Lehigh Valley already enjoy from the reservoir. We believe the Army Corps of Engineers might find ways to manage the reservoir differently to improve fisheries and boating, and potentially make additional releases for recreation without compromising its mission of flood protection.

Our opinion is based on recent changes that we’ve made to the operation of New York City’s reservoirs on the headwaters of the Delaware River. As I mentioned, our reservoirs are drinking water reservoirs. Their primary goal is to provide a reliable quantity of clean, unfiltered drinking water to New York City throughout the year.

Until about 20 years ago, they were operated essentially to meet that mission alone. For decades, New York City kept its reservoirs as full as possible for as long as possible. We operated them to fill and spill as often as we could, and relatively little attention was paid to other interests, stakeholders or management options.

That is not the case now. Advancements in technology and science have allowed us to predict, quantify, and ultimately release additional water from our reservoirs into the Delaware River to meet the needs and desires of downstream stakeholders. Thanks to dozens of river gauges, modern runoff forecasts, snow measuring equipment, and computer models that can process massive amounts of data, we now operate our reservoirs to support the cold-water fishery of the Upper Delaware River, increase the flood attenuation that our reservoirs already provide, and carry out our primary mission of supplying drinking water at the same time.

Instead of filling and spilling the reservoirs, we now meticulously examine the amount of water coming into the system on a daily basis and proactively release water downstream with the goal of filling our reservoirs by June 1, which is the start of our water year, while also minimizing the amount of water passing through their spillways. This management strategy results in larger releases downstream throughout the course of a typical year, which is great for the cold-water fishery, the businesses that depend on it, and the natural ecology of the river.

In 2020, for example, 182 billion gallons of water from our Delaware System reservoirs were used for drinking water, while 230 billion gallons from those reservoirs were proactively released downstream as a result of changing our operational philosophy. We cannot overstate how differently we operate these reservoirs now compared to just 20 years ago – all because we remained flexible, responded to the needs of more stakeholders, and applied sound science to our operations.

We used objective science and advanced forecasting to successfully guide operational changes at New York City’s reservoirs, and we believe similar strategies could be applied to other reservoirs throughout the Delaware Basin. In fact, the Army Corps of Engineers has already implemented forecast-informed reservoir operations in its Southern Pacific Division, which oversees many reservoirs in California. We believe the North Atlantic Division could apply this operational strategy to F.E. Walter Reservoir to enhance all the benefits that are seen during a typical year, and provide low-flow augmentation during severe droughts when additional freshwater will be needed to protect community water supplies, including those in Pennsylvania.

This study of F.E. Walter Reservoir is part of a broader set of studies and conversations that are happening among the states of Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, New York City, and the DRBC. Each of those entities – and everyone at this hearing – has an interest in periodically examining water resources throughout the Delaware Basin to ensure they are being used properly, flexibly and efficiently to meet the challenges facing our communities now and in the future.

To conclude my testimony, I want to reiterate that New York City is not interested in drinking water from F.E. Walter Reservoir, nor are we interested in any control over the reservoir. We believe this study by the Army Corps of Engineers could benefit the entire Delaware River Basin, but especially folks in the lower basin who will face more numerous and difficult challenges as climate change and sea-level rise continues. Most importantly, the outcomes of this study must be driven by sound, objective science, with an eye toward benefits for everyone who has a stake in the operation of F.E. Walter Reservoir. This is not about what’s best for New York City – it is about what is best for the Delaware River and the people who depend on it.

Thank you again, and I look forward to answering your questions.

Jennifer Garigliano has served as the chief of staff for New York City’s water supply since 2012. Garigliano graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 2007, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in environmental engineering and was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army. Garigliano served one tour of duty in Afghanistan, for which she earned a bronze star. She continued her service at Fort Richardson in Alaska and later transitioned into the reserves. In 2021, Garigliano was appointed president of the Water Resources Association of the Delaware River Basin.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)