Special report: Large vessels on the Delaware River lose steering, propulsion or power monthly

| March 26, 2025

Large vessels on the Delaware River have lost power, steering or propulsion an average of at least 13 times a year from January 2013 through January 2024, putting bridges and other vessels in danger of a catastrophe similar to what happened in Baltimore last year, according to U.S. Court Guard data exclusively analyzed by Delaware Currents.

Most of the incidents occurred near bridges and ports, especially PhilaPort in Philadelphia and the Port of Wilmington in Delaware, which are the two largest ports on the river, the data showed.

Apart from two incidents that resulted in minor damage, the Coast Guard data had no reports of crashes involving infrastructure, such as bridges, piers or docks, or collisions with other vessels. However, the data does reveal for the first time how often these losses of power, steering or propulsion — which can be precursors to disaster — have occurred on the Delaware River.

Data analysis exclusive to the Delaware

It was a year ago today that the Dali, a 984-foot-long cargo ship, crashed into the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, killing six construction workers and resulting in an estimated rebuilding cost of as much as $1.9 billion.

The causes of the crash were two electrical blackouts that led to a loss of propulsion, according to a preliminary report from the National Transportation Safety Board.

In the aftermath of that disaster, news outlets explored the frequency of such occurrences. For instance, a USA Today analysis of Coast Guard national data from 2002-24 found that vessels were reported to have lost power, propulsion, steering (or a combination of all three) at least 6,000 times over that period, or an average of more than five times a week.

However, the data obtained by Delaware Currents, which has not been reported before, focused exclusively on such incidents in the U.S. Coast Guard Sector Delaware Bay’s Area of Responsibility, which covers the Delaware River from the Atlantic Ocean and includes parts of Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as well as the ports of Philadelphia and Wilmington.

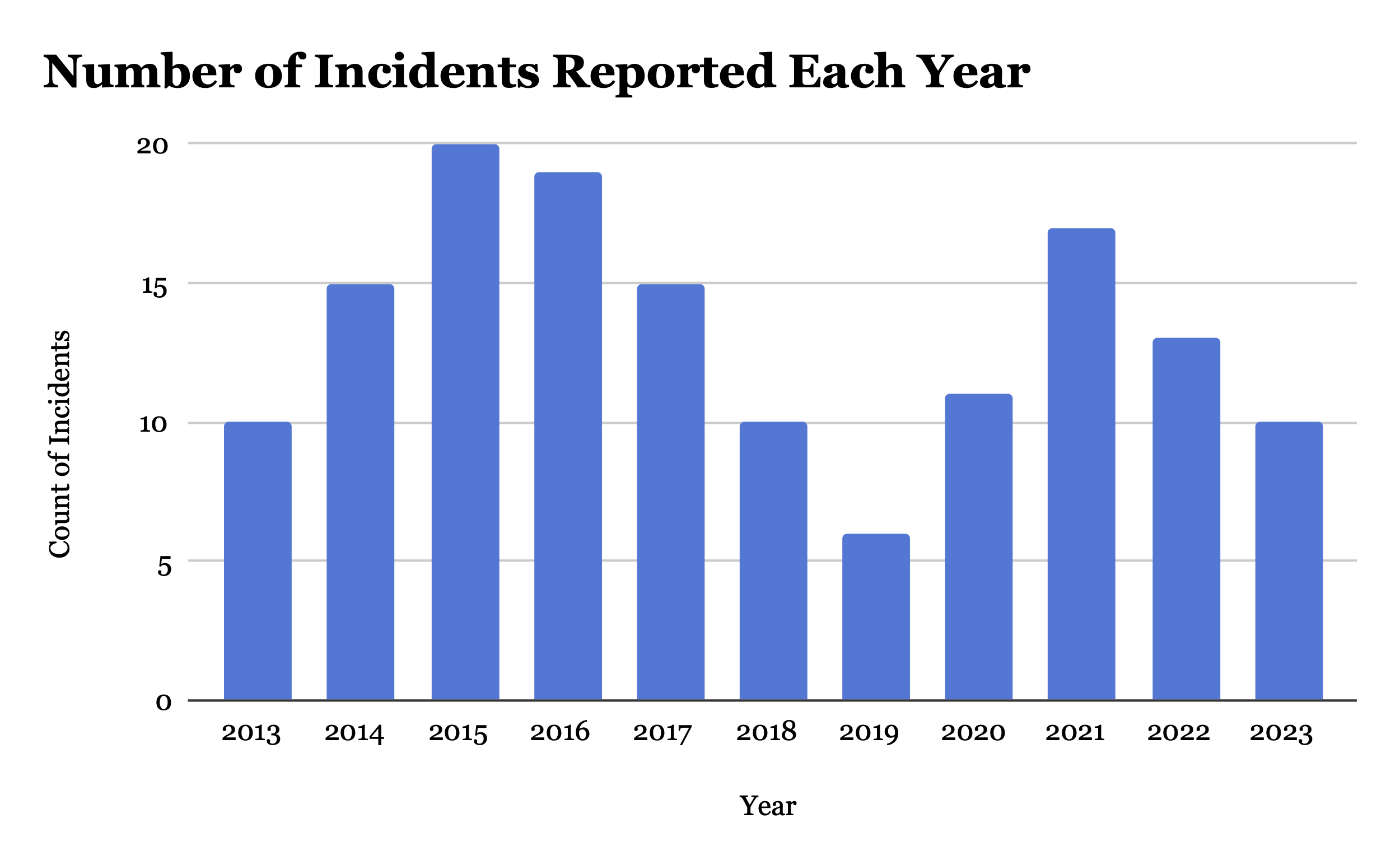

The Delaware Currents analysis focused on cases known as “marine casualties” involving vessels longer than 400 feet that had a loss of propulsion, power or steering from January 2013 to January 2024. The greatest number of incidents, with 20, were reported in 2015, with 2016 following closely behind, with 19. The lowest number reported was in 2019, with six, the data show.

A footnote about the chart: One incident recorded in January 2024 was not included as data for the entire year of 2024 was not readily available.

Of the 147 incidents reviewed by Delaware Currents, nearly 40 percent happened in or around the major ports along the Delaware River, including the Port of Philadelphia, the Port of Wilmington, and the Marcus Hook, Mantua Creek and Kaighn Point anchorages.

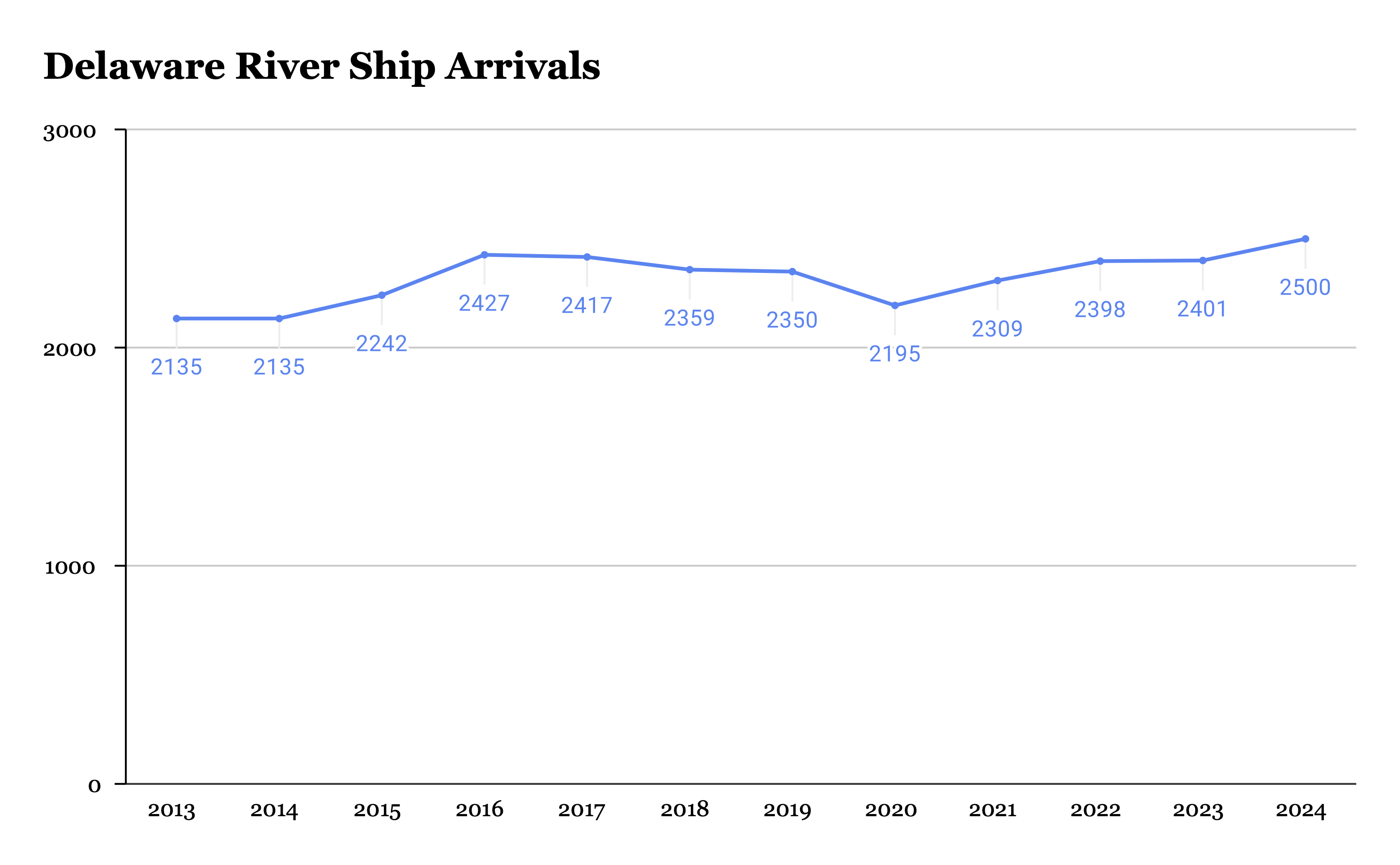

Nearly 28,000 ships arrived to the Delaware River over the 11-year period that was analyzed, an average of almost 2,600 ships per year. On average, the number of ships arriving on the Delaware increased 1.5 percent each year from 2013 to 2024, according to data from the Maritime Exchange for the Delaware River and Bay, a nonprofit trade association.

Multiple messages left for the communications departments at the Port of Philadelphia and Port of Wilmington were not returned.

The area of the Delaware River that the Coast Guard data covers, from Trenton, N.J., to the Atlantic Ocean, includes eight bridges. Of those eight bridges, five were among nearly 70 across the country in need of risk assessments for potential collapse, according to an NTSB report from March 18.

The five include: the Delaware River-Turnpike Toll, Betsy Ross, Benjamin Franklin, Walt Whitman and Commodore Barry Bridges. The other bridges covered in the data include the Delaware Memorial, Burlington-Bristol and and Tacony-Palmyra Bridges.

What causes these incidents?

Coast Guard records cite various causes for losses of power, propulsion or steering. The most common: faulty wiring and valves, malfunctioning fuel pumps or engine failures.

In two cases in 2018, a “significant amount” of unspecified debris in the river was to blame. In two others, human errors were flagged, including one where an engineer failed to “reinstall securing bolts to the field injector” after routine maintenance, causing the vessel’s main engine to catch fire.

The low number of reported human errors was surprising to Jason Merrick, an expert in maritime risk assessment and a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University.

He compared the maritime industry to aviation. In aviation, the reporting of human errors is encouraged without fault assigned to those who made the mistake. But if a human error is later discovered to have gone unreported, it can lead to firings and huge fines.

In the maritime industry, he said, “You don’t have the same level of human error reporting, even though we know that human errors are the primary cause.”

Merrick offered a hypothetical story of a police officer helping someone who lost their keys on a dark road, and the driver is searching for the keys under a streetlight, where they can see, despite the higher probability that they dropped the keys in the dark.

“That’s always true with data,” he said. “Often the answer is somewhere in the dark where the data hasn’t been collected. We often get a dataset together and look at that dataset, but even if it shines a light, it’s not where we dropped our keys.”

No foolproof safeguards

Scott Roosevelt, a former marine tug operator of 15 years and now a docking pilot with just over a decade of experience working with large vessels on the Delaware River, described the marine casualty incidents as “flukes.”

“There’s no really predicting them, because you assume everything’s working,” he said. “It’s the same as a car. You start your car to go to work, and you’re like, ‘We’re good,’ and then you’re not.”

Roosevelt added that there aren’t preventative measures to stave off a system malfunction that could lead to loss of power, steering or propulsion. There is, however, planning to safely maneuver large vessels on the river, especially when passing under bridges, he said.

He cited the complex planning to move the SS United States, a 1,000-foot-long historic cruise ship from Philadelphia to Florida where it will be sunk to become the world’s largest artificial reef. To fit under the Walt Whitman Bridge, the ship could only travel during low tide. “Everything was predicted,” Roosevelt said.

Switching fuels can be a source of trouble

As vessels draw closer to a port, they have to shift to lighter fuels because of the environmental impact of the thick, dark exhaust emitted by heavier oils more commonly used at sea.

That shift in fuels could lead to a loss of power or propulsion, and could explain the higher number of incidents near ports, according to a 2017 report by the London P&I Club, a maritime insurance firm.

In January 2016, a 25-year-old refrigerated cargo ship, the Comoros Stream, was arriving at the Wilmington anchorage when its pilot ordered “astern propulsion to maneuver into position,” or ordering the ship’s engines to reverse to slow the vessel before dropping anchor, when the main engine did not respond.

Several minutes later, the vessel responded. According to investigators, the cause of the loss of propulsion was “the failure of the high-pressure fuel pumps to deliver sufficient fuel to the propulsion engine, which led to the vessel losing main engine propulsion and maneuverability.”

Coast Guard records said the vessel’s fuel pumps had only pumped heavy fuel oil for the past four years and had not pumped a lower-viscosity oil, such as low-sulfur marine gas oil, which was required ahead of its arrival at an emissions control area.

On the Delaware River, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, vessels described as “difficult to handle” or that have a history of handling poorly, “must transit the canal during daylight hours and must have tug assistance.”

Capt. Joseph Ahlstrom, professor at the State University of New York’s Maritime College, described tug escorts as “essential.” Tugs are expensive but “it’s cheap insurance,” he said. “Prepare for the worst and enjoy the best.”

Still, the use of tugs is not a guaranteed way to avoid problems, experts said.

For instance, in the Dali’s case, two tugs helped on its departure, but “per normal practice,” according to the NTSB’s preliminary report, the senior pilot ordered the tugboats to be let go. At 1:26 a.m., the pilots called for tug help, but the tug was three miles away. It didn’t reach the Dali before it struck the bridge at 1:29 a.m., the preliminary report found.

Roosevelt said that if a tug were connected to a vessel like the Dali when the loss of power occurred, it could help to stop it, but you “have to build in the stopping distance.”

The time it takes to stop a large vessel using a tug varies, “depending on the size of the ship, the drift of the ship, the weight, the horsepower of the tug, all that,” he said.

Taking steps to guard Delaware bridges against crashes

There were no reports of vessels crashing into bridges along the Delaware River during the 11-year timespan covered in the Coast Guard data. Nonetheless, measures are being taken to prevent a catastrophe like the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge.

A.J. Schall Jr., director of the state Delaware Emergency Management Agency, said it has “conducted assessments of loss of infrastructure for several different types of scenarios, several involving bridges, and specifically the Delaware Memorial Bridge.”

Michael Chajes, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Delaware, said that while bridge owners do a “fairly good job” of making sure their structures are up to standards required by federal law, “as time goes by, ships get larger, or as we learn new things, sometimes we find out that there are conditions that we haven’t necessarily designed for.”

These standards, known as the National Bridge Inspection Standards, have changed dramatically over the years. The Delaware Memorial Bridge was constructed in 1951, but updates to the inspection standards for highway bridges have been made as recently as 2022.

Chajes said bridge operators are looking for vulnerabilities to mitigate the risks of large, ever-growing vessels. He pointed to a $93 million dollar project aimed at updating a system that protects the Delaware Memorial Bridge against ships crashing into one of its two towers.

Four cylinders will be installed at the piers supporting the eastern towers and four will be installed to protect the western towers as a barrier against a ship in the event of a crash. The original system consisted of fenders that functioned similarly to the cylinders being installed now, but they were designed to withstand less force.

“It really comes down to a matter of money at this point,” Chajes said. “But the Delaware River and Bay Authority understands the tradeoff of either we spend this, or we risk having these bridges come down.”

Greg Pawlowski, senior project engineer with the Delaware River and Bay Authority, said the agency started looking into the protection system years ago. But, when recommendations were initially made to defend the cost of the project, the major question was the probability of whether a bridge would be hit.

Until the Baltimore bridge collapse, Pawlowski said, “everybody thought the chances were pretty slim.”

HOW WE DID THIS STORY

For nearly a year, Delaware Currents analyzed a first-of-its-kind, custom-made database compiled by the U.S. Coast Guard’s Sector Delaware Bay.

We searched each incident to find its corresponding details, filed public records requests for incomplete or missing data, reviewed news reports and interviewed experts on marine and civil engineering, including a docking pilot, multiple professors, civil engineers and a data scientist with a special interest in predictive analytics for marine casualties.

We discovered that it’s nearly impossible to predict when a major catastrophe like the one in Baltimore can happen.

To compile the dataset, the U.S. Coast Guard’s Office of Investigations and Casualty Analysis ran a query into the Coast Guard’s public-facing database, its searchable Incident Investigation Reports.

The query covered investigations from 2013-24 involving “reportable marine casualties” with “a loss/reduction in propulsion or steering or loss of electrical power events” involving vessels greater than 400 feet long in Sector Delaware Bay’s area of responsibility. The query returned 147 incidents.

As you’ll see on our interactive map, some incident coordinates were recorded on land, though it’s unclear why.

Eighteen incidents — clustered between August 2014 and August 2015 — lacked corresponding investigation details. On the interactive map, you’ll see that these incidents do have location data and year of occurrence but no other accompanying information.

In August, Delaware Currents filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the missing incident investigation reports. Another request for those same reports and more expansive details was filed in early February. Multiple voicemails left for the point of contact for FOIA requests at the Coast Guard were not returned.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)

Excellent research and reporting.