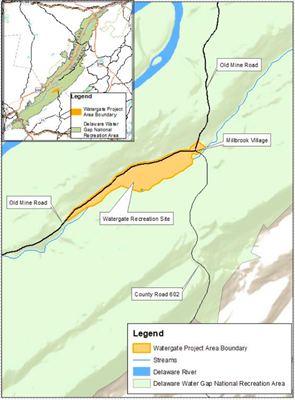

Watergate wetlands are restored in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

Animals and plants are expected to thrive after dams and ponds were removed and parts of Van Campens Brook restored

| January 10, 2023

When the National Park Service studied visitation at the Watergate Recreation Site in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area it found that most people stayed for just three to seven minutes.

The site, which is about 11 miles west of Newton, N.J., had gone through numerous iterations before arriving at that unpopular version of itself.

Its natural state is a wetland, but that began to change with European settlement in the early 1800s. Farmers grew grain and hay and raised livestock, and “to create more usable farmland, the inhabitants installed dikes and ditches to drain the wetlands,” according to an environmental assessment completed by the NPS.

The farmers also rerouted Van Campens Brook “to the side of the valley to create more arable farmland,” said Kristy Boscheinen, manager of the wetland restoration project.

The Columbia-Walpack Turnpike was built alongside the stream, which reinforced the stream in place, she said.

Starting in the 1930s, and continuing after World War II, vacation homes replaced these farms, whose profitability had declined as they were outpaced by more productive farmland elsewhere, Boscheinen said.

Wealthy New York City jeweler George Busch bought up farms in the 1940s and added two groundwater-fed ponds along Van Campens Brook. He built a “mansion-like” house for himself and additional smaller homes, she said.

Those were demolished when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers bought the land in preparation for the Tocks Island Dam, which was never built and would have created a reservoir on the Delaware River.

“And so, once Army Corps passed it to the National Park Service, we made a decision that we were just going to keep managing it as a recreation site,” Boscheinen said.

The NPS kept a mowed lawn that Busch had created. It added a bandshell, though it’s no longer there, and considered amenities such as a beach and bathhouses, which the NPS ultimately chose not to build around the hot, shallow ponds.

“There used to be a lot of weeping willows and linden trees,” Boscheinen said, adding that it was a “very park-like” setting for picnics before a series of storms took out many of the trees.

And since 2013-14, Susquehanna-Roseland power line towers that are 195 feet tall have loomed over the view. The line crosses Old Mine Road just west of Watergate.

Limited number of visitors

When the NPS studied visitation, it found that the ponds did get some use by anglers. But others stopped just to use the flush toilets, and picnickers “would look at this landscape of geese and a mowed lawn” and decide the site’s fee of $10 per vehicle wasn’t worth it, Boscheinen said.

In 2015, for example, only 94 passes were purchased at Watergate compared to 2,998 at Smithfield Beach during July, the recreation area’s busiest month.

But the Watergate site was very appealing as a restoration project. Bringing back the wetlands there was “by far the best” option out of about 10 projects considered by the Park Service when it had to decide how it would mitigate the impacts of the transmission line upgrades, Boscheinen said.

In this type of wetland, “the groundwater is right at the surface,” she said.

Data collected across the site at all times of the year under different conditions showed that groundwater could be from six inches to seven feet under the surface.

Read more: National Park Service removes dams on Van Campens Brook in Millbrook Village, N.J.

“So, when we were constructing the wetland, we had to be at zero feet. So that gave us a model” for how to make sure it was neither too dry nor too wet, Boscheinen said.

Equipment operators moved earth in a “super precise” way, removing just the right amount to bring groundwater to the surface, Boscheinen said. All the planning and careful work began paying off immediately.

Despite the dry summer the region experienced, “the wetlands were there,” Boscheinen said, “even while we were still in the process of replanting and reseeding and stuff.”

The appropriate “mucky soils” were developing, followed by a flush of growth from both NPS plantings and the native seed bank – old seeds that were ready to sprout once wetland conditions were re-established.

“We scraped off all the turfgrass and top few inches of soil to try to get rid of most of the non-native seeds, since invasives have become so prolific onsite in recent decades, and hauled that material offsite. After all the earth-moving was done, we re-seeded with native plant species,” Boscheinen said.

“We were surprised to find a lot of germination of species that we didn’t seed, such as sedges and other wetland plants,” she said. “Birds or other animals couldn’t have brought them onto the site in such quantities, so our conclusion is that there was still a viable native plant seed bank that had been buried all these years.”

Seeking a diversity of plantings

The NPS considered climate change and the potential arrival of new invasive species when it decided what to plant. A diversity of species is important, Boscheinen explained, because when something like the emerald ash borer moves in, “one thing can happen and you lose 50 percent of that kind of tree.”

“So, what we chose to plant was a mix of species that are currently here, or in this region of the Appalachians, so native to this area, as well as species that are more generalist. So, looking at plants that grow from Virginia to Maine, and New Jersey to Michigan,” Boscheinen said.

That means, for example, planting two types of dogwood shrub, one native and suitable across a broader area.

Animal life is also expected to thrive in the wetlands.

“We had geese actually nest in one of the wetlands this spring. Tons of animals out there,” Boscheinen said. “That’s the good thing about wetlands, right? They’re so diverse.”

Van Campens Brook will cool off due to a combination of new vegetation, creating shade and the removal of the ponds. Though the largest ponds were groundwater-fed, they had outlets into the stream, Boscheinen explained.

“I swear they would be like 90 degrees in the summer,” she said — not ideal for the coldwater trout in the brook. “We’ve been monitoring stream temperature above and below the project area and will continue to do that. And we expect that we’re going to see a really positive change that it’ll be colder.”

As the stream cools, the rusty crayfish, which was starting to creep up Van Campens Brook, will be pushed back out by lower temperatures, which it can’t tolerate. The species kills native crayfish and eats trout eggs.

Similarly, non-native brown trout are present at higher temperatures and “they also harm the native trout fishery because they out-compete the trout,” Boscheinen said.

The Park Service will monitor groundwater levels and vegetation, tracking how much plant coverage there is and how much is native.

With dams removed and the wetlands restored to their natural geography, Van Campens Brook will be able to spread into its natural floodplain during heavy rain events.

“We had a photo from 1920, just above the project area in Millbrook Village, where there was a summer thunderstorm. It was about four hours and it cut a channel like six feet deep in the Columbia-Walpack Turnpike, right next to the stream. So, the stream had jumped its reinforced bank, and then carved out a big chunk of this road,” Boscheinen said.

Millbrook Village today is home to a mix of original buildings, relocated buildings and recreated buildings. The restoration project site begins just south of the village.

Part of it is within the Van Campens floodplain, and although the village once lost a bridge to Hurricane Ivan in 2004 and then lost its replacement to Hurricane Irene in 2011, Millbrook Society Vice President Fred Schofer says that “now I’m more concerned with getting the buildings up to snuff” and with resuming the events that were shut down after the pandemic began.

The wetlands will remain closed to visitors for six to 12 months “just to let the soil stabilize” without getting compacted by footsteps that would prevent seeds from sprouting, Boscheinen said.

When it does reopen, sometime in 2023, the transformation should draw in visitors for far longer than three to seven minutes.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)

Awesome job