DRBC hearing outlines dry conditions and possibility of calling a drought for the Delaware River

| November 19, 2024

The Delaware River Basin Commission held a public hearing on Tuesday to gather comments about the abnormally dry conditions throughout the four-state watershed.

It was hard on the heels of New York City’s announcement on Monday that it was suspending its long-planned work on the Delaware River Aqueduct, which would plug a leak in the tunnel that carries about half of New York City’s water under the Hudson River.

There really wasn’t much new news out of the hearing, though a general introduction to the situation in the river and its four-state watershed was provided by Amy Shallcross, the DRBC’s manager of water resource operations.

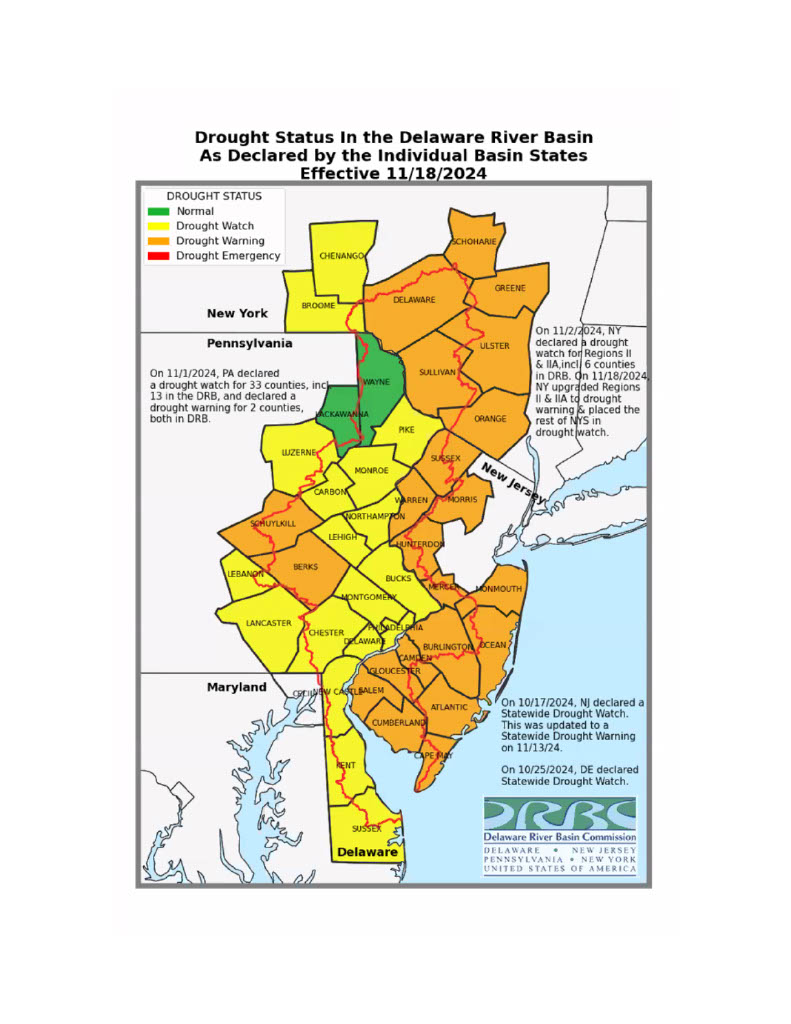

Basically, the land near the river can be in a drought alert, but that doesn’t mean the river itself is.

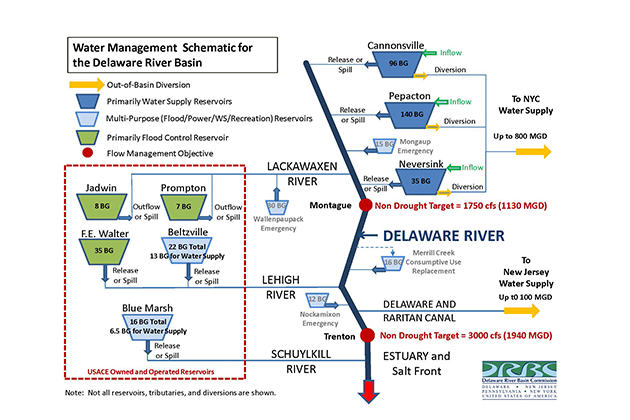

The river’s drought status is largely dependent on the amount of water in New York City’s three Delaware River reservoirs, Pepacton, Cannonsville and Neversink, and is declared by the commissioners, who are the governors of the four states and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The meeting officer for the hearing was Kristen Bowman Kavanagh, the deputy director of the DRBC, and soon to be its executive director.

That drought status could be declared, basically, as the need arises. Kavanagh said the DRBC will endeavor to provide a 10-day notice, if possible, or it might act more quickly. Or it could wait until its fourth-quarter business meeting on Dec. 5.

Salt front is encroaching

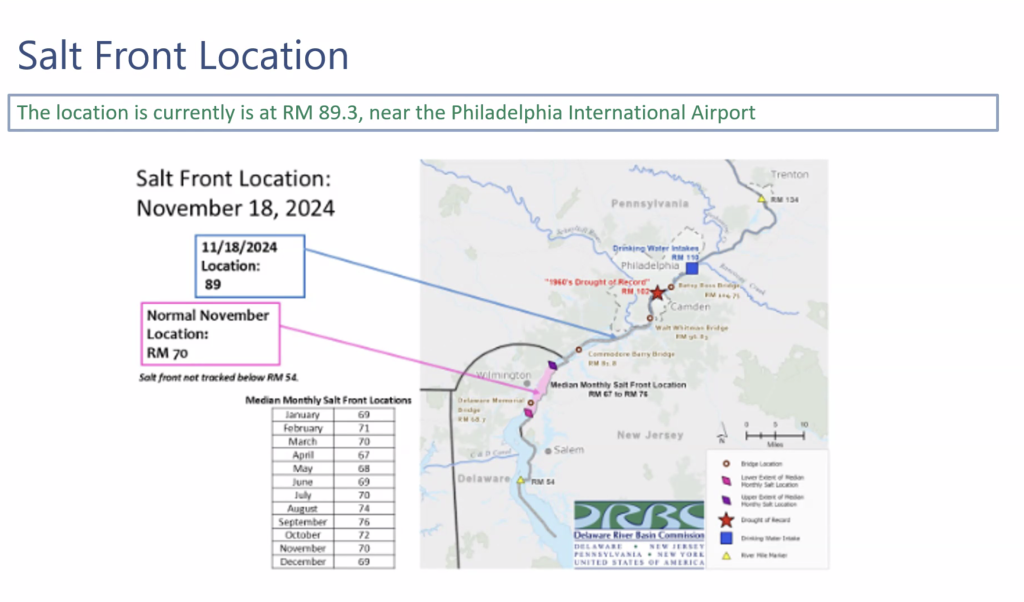

For the basin right now, the big problem with the lack of water is the salt front, which is where salty ocean water meets the fresh water coming down from the upper river.

That salty water can affect drinking water intakes on the river, as well as industrial users.

That salt front is 19 miles farther upriver than usual for this time of year, at river mile 89 (counting from zero at the mouth of the Delaware Bay). The salt front varies with the force of salt water coming upriver from the ocean and how much fresh water pushes it south. That location is near the Philadelphia Airport.

The DRBC’s drought operations plan is designed to preserve regional storage and repel salinity. In other words, you only want to use enough water to push that salt front away but not waste the valuable resource.

The plan is based on New York City reservoirs’ storage as well as reservoir storage in lower basin reservoirs.

The stipulated flow in the upper river is 1,750 cubic feet per second as measured at Montague, N.J. That was ordered in a U.S. Supreme Court amended decision rendered in 1954. That flow is overseen by the Delaware River Master.

And the River Master, now Kendra Russell, follows the agreements among the decree parties (Delaware, New Jersey, New York, New York City and Pennsylvania) called the Flexible Flow Management Plan, most recently signed in 2017.

The drought plan calls for phased reduction in flow objectives, or for increases based on the salt front, and for phased reduction in out-of-basin diversions and reductions in reservoir releases.

It will allow access to additional reservoir storage — the DRBC has storage in Army Corps reservoirs. Merrill Creek Reservoir is additional storage to offset consumptive use by power companies.

The last step in this plan is voluntary water conservation.

One hopeful outlook, Shallcross noted, is the prediction for rain later this week, which, of course may or may not happen. The other is that this is a La Nina year, which ordinarily means a warmer, wetter winter.

Speakers concerned with development

There were 10 scheduled speakers, among them Faith Zerbe, the Water Watch director for the Delaware Riverkeeper Network who wanted the DRBC to be more proactive in fighting the effects of climate change by viewing all projects it reviews through a climate-change lens.

She suggested it could deny projects, like warehouses that pave over open space, uphold protections for small streams and protect flood plans and wetlands.

Christine Martin, who is on the Upper Delaware Council, representing the Town of Highland, N.Y., spoke as a private citizen, not representing the UDC. Her concern was the FIFMO project, which she called an “over-development of sensitive land near the river.”

The plan put forth by the developer, Northgate, includes camping accommodations, a water playground, sports courts, a heated swimming pool and more, spread over more than 220 acres in her town in the Upper Delaware. One of her biggest concerns was the outsized water use that the project entails, and “disputed figures on water usage.”

Mary-Ellen Seitelman, also from the Upper Delaware, was concerned about the Town of Bethel, also in Sullivan County, N.Y., where she said construction was “out of sight” and that no one was taking into account the cumulative effect of building dormitories and expanding bungalow colonies, without new guidelines for wells.

“Builders continue to make more money while the rest of us suffer,” she said.

It needs to be said that the DRBC has traditionally — and per its compact — kept its eye on the river, leaving land use to the watershed states. But the demand from speakers was asking the DRBC to move into a broader role.

A viewpoint echoed by Karen Feridun, founder of Berks Gas Truth and co-founder of Better Path Coalition:

It’s so important to have a Commission like this one that can manage problems and mitigate their impacts, but it’s even more important to have a commission dedicated to preventing them. You receive excellent reports on climate change and have convened a committee with an impressive list of members to discuss climate change, but those things don’t matter if you continue allowing fossil fuel projects to move forward, either by approving permits or by failing to assert your authority over projects that you have the power to stop.

We know that 1,773 fossil fuel lobbyists are attending the U.N. climate talks being held in a petrostate this year and led by a fossil fuel executive who was caught on film promoting fossil fuel deals at COP29. We now know that climate deniers will occupy the top positions in our federal government. It is up to commissions like the DRBC and the governors of each of the member states to take the lead on climate.

Clearly issues of water use, lead into land use and on into even bigger problems, exacerbated by climate change.