EPA seeks to remove all lead water pipelines in 10 years

| March 11, 2024

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is expected this fall to roll out new rules requiring the removal of lead water pipelines, ushering in the first nationwide effort to replace millions of pieces of infrastructure that can have harmful health effects but that also raises questions of how to pay for the $625 billion in needed improvements.

As lead pipes corrode, they can leach lead particles into running water that you could eventually end up drinking.

In an adult body, lead can cause heart problems, neurological damage and cancer. But lead is even more toxic to children under 6, causing brain damage that can slow development, lower IQs and increase behavioral problems.

The EPA’s new proposal — known as the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, or LCRI — would require all public water systems to remove lead service lines within 10 years, among other proposed changes to regulations in the EPA’s 1991 Lead and Copper Rule.

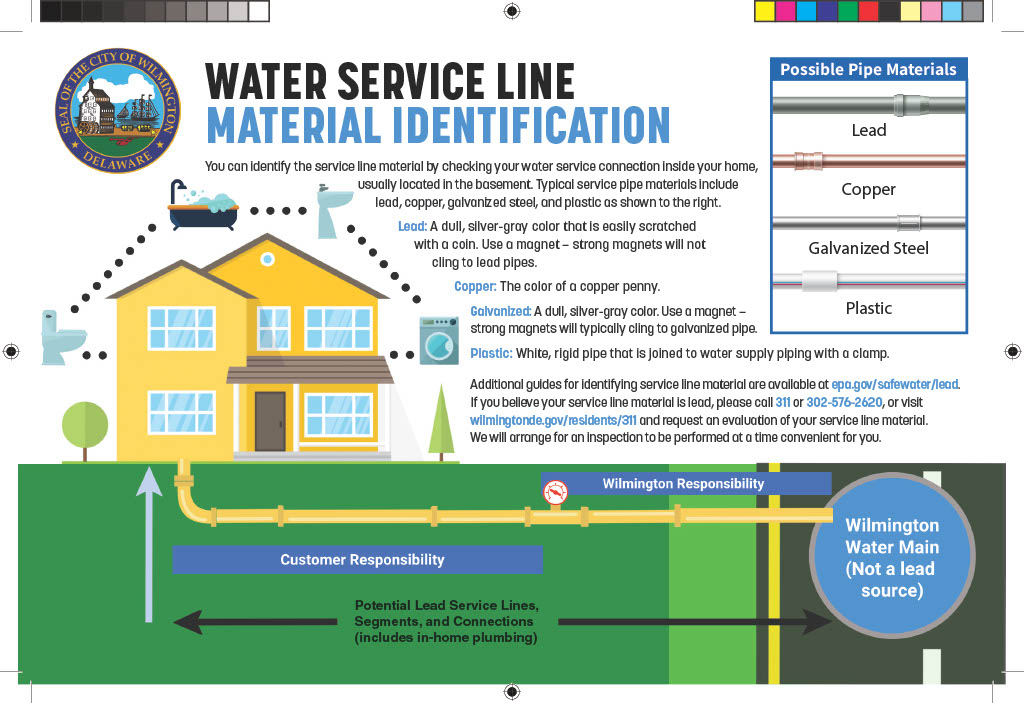

The lead lines, formally known as lead service lines, are the pipes that connect your home’s plumbing system to the public water system’s main water line.

The federal government banned the use of lead pipes in 1986 but lead lines already buried were allowed to remain. The EPA believes there could still be about 9.2 million individual lead service lines in the United States.

Delaware River watershed figures

The four states in the Delaware River watershed alone account for 1.5 million of the nation’s estimated lines, according to the EPA, with Pennsylvania having the fourth-highest number in the country at 688,697 — around 7.5 percent of the nation’s total.

Officials in many cities in the Delaware watershed say they’re sitting on thousands of lead pipes that are well over a century old.

A 2023 EPA report estimated that New York had the sixth-highest number of lead service lines, at over 494,000, while New Jersey had nearly 350,000, and Delaware had almost 43,000.

But the EPA admits these numbers are an educated guess — a projection based on each state’s provided numbers of known lines. In reality, many local water departments are still trying to inventory the lead pipes in their systems.

The EPA’s proposal is drawing criticism from localities that say they need more funding and from lead-free advocates who want faster action.

Members of the coalition Lead-Free Delaware say the EPA’s proposal doesn’t go far enough to protect people — especially school children — from the dangers of lead.

“The EPA needs to have stronger regulations that protect health,” said Sarah Bucic, co-chair of Lead-Free Delaware. “This is like, 2024, you know? This is really preventable. We shouldn’t be talking about this decades after we knew it was bad in gasoline … it’s incredibly expensive — that’s part of it — but so is what lead does.”

Some municipalities in the watershed fear that the EPA’s 10-year timeline could be too aggressive to be realistic, especially for cities still early in their lead line inventory, like Wilmington, Del.

“It’s going to be difficult to comply within 10 years,” said Chris Oh, Wilmington’s water division director.

Water customers technically own the portion of the lateral line that runs from their street to their plumbing system, which means customers — or taxpayers in the case of public schools — could bear some direct costs for replacement projects.

The proposed rules don’t take a stand on who foots the bill for customer-side pipe replacements — whether it’s the customer or the water provider — but the EPA is encouraging water utilities to enroll customers in free or low-cost lead line replacement programs to boost participation.

Local leaders say unclear funding sources for line replacement projects could ultimately end up raising customers’ water rates.

More stringent cutoff on lead levels

The new rules would also lower the “lead action level” in drinking water to 10 parts per billion (ppb), from 15 ppb. The lead action level is the highest level of lead a public drinking water source can have before it must be remediated or shut off.

The new rules would apply nationwide but states can also create their own, stricter rules on lead and some watershed states already have.

Delaware has the lowest statewide lead action level for drinking water in the watershed at 7.5 ppb. New York follows the EPA’s 15 ppb guideline, though in 2022 the state lowered its action level in public schools to 5 ppb.

While Pennsylvania and New Jersey also use the EPA’s rules for lead action levels, New Jersey has adopted its own stringent lead pipe regulations, requiring public water systems to remove lead lines by 2031.

The proposed 10 ppb action level is a sticking point for groups like Lead-Free Delaware, which say the EPA should comply with its own maximum contaminant goal for lead in drinking water, which is zero.

The EPA would also encourage water systems to replace lead service lines in the most “efficient” and “equitable” way possible, acknowledging that the effects of lead poisoning are most often felt in underserved, low-income communities and communities of color.

The proposed rules just moved through a public comment period and are expected to go into effect by October, according to the EPA.

Water systems would have a three-year period to plan a lead line replacement program before the 10-year replacement period begins, setting the replacement deadline around 2037.

A heavy history

Lead pipes’ durability and malleability made them one of the most popular plumbing choices in the 19th century.

By 1900, lead piping ran through more than 70 percent of U.S. cities. But the dangers of lead were known well before lead pipes were banned in 1986.

People in the United States knew lead was poisoning them by the 1800s, and by the 1920s, cities were passing their own bans on lead pipes.

The lead industry countered with an aggressive lead pipe campaign.

The Lead Industries Association, or the LIA — a coalition of lead manufacturers and mining companies — started lobbying government officials, working with organizations of plumbers and even trained its own workforce of plumbers certified in lead pipe installation.

The association published a “model” standard for lead pipes and published “Useful Information About Lead” in 1931, which warned against using lead only “when the water is very soft, or of swampy or peaty origin.”

“Under those conditions,” it said, “other metals are also soluble, so lead may be used by adding a little sodium silicate solution to the water, as is done occasionally — or using tin-lined lead pipe.”

By 1938, the LIA had convinced the state of Pennsylvania — as well as dozens of cities in the U.S. — to rewrite their plumbing codes to require lead plumbing in public water systems.

The LIA didn’t acknowledge the dangers of lead in its publications. LIA members publicly blew off claims that lead was dangerous by denying data from studies on lead paint poisoning in the 1940s but evidence against lead mounted in the 1950s.

The association fizzled out in the 1970s, just as state and federal regulations on lead poisoning were ramping up.

Funding the new lead pipe rules

The EPA is promoting $15 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law — as well as $11.7 billion of federal drinking water funds — as sources for lead line replacement projects but otherwise hasn’t laid out a long-term, large-scale plan for funding the projects.

Philadelphia, where an estimated 20,000 homes have lead lines, got $160 million in federal funding in 2023 as the city replaces miles of water mains and the lead service lines that branch off them.

The city also received a $340 million federal loan agreement last year to upgrade its water infrastructure, with the first EPA-administered $19 million loan expected to cover 15 miles of new water mains and 160 line replacements — an early project in the city’s multi-billion dollar plan to upgrade its water infrastructure within 25 years.

The EPA estimates that water providers in the U.S. would need almost $625 billion to update their water infrastructure over the next 20 years, with the Delaware River watershed statesexpected to need at least $72 billion for their portion of the work.

With more communities expected to seek funding, water providers worry there won’t be enough money to go around.

“Everything the water utility does in capital work is measured in millions,” said Michael Walker, chief of communications for the city of Trenton, N.J. In Trenton, lead service line replacements can cost between $7,000 and $10,000 per line, he said.

States are starting to funnel money piecemeal toward replacement projects.

Allentown, Pa., got a $3.4 million grant and $1.6 million low-interest loan from the Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority, or PENNVEST, for a pilot project to remove 150 lines, including customer-owned lines.

The funding itself covers only a fraction of the city’s estimated need for 7,700 line replacements, according to Susan Sampson, a spokeswoman for the Lehigh County Authority.

The city of Port Jervis, N.Y., replaced around 30 lines last year in the city’s Fourth Ward with a $603,855 state grant. The city’s public works director, Steve Duryea, said the laterals cost $22,000 per line to replace — a daunting price tag in a city where more than 80 percent of 3,000 residential lines are made of lead.

Trenton’s water department has already spent around $50 million to replace 30 percent of its more than 16,000 suspected lead lines, an effort largely backed by municipal bonds from the New Jersey Infrastructure Bank.

To help with the loan payments, the city recently had to raise its water rates for the first time in a decade, Walker said. In Trenton alone, Walker said he expects line replacement projects to cost between $150 million and $200 million.

Cities like Port Jervis and Wilmington have launched customer surveys and sent mailers asking homeowners to test their pipes for lead. It’s a low-cost way to gather data, in addition to scouring service records and predicting where lead service lines could be based on the age of an area’s housing stock.

But Wilmington and Allentown officials say they need more customer participation in the surveys to meet the EPA’s inventory deadlines this October. They also need more money to inspect customers’ pipes.

“We won’t know until we can get out there,” Duryea said. “I wish I had better answers. But until we get some better funding, I think we’re all on the same page.”

To help your local water department with its inventory, scratch your water pipes with a coin. If the pipe feels soft and scrapes easily, call your water provider and report it.

It could be lead.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)