Polluted streams continue to plague Delaware River watershed in Pennsylvania

| November 20, 2023

The quality of water in the Pennsylvania sub-basins that make up the Delaware River watershed deteriorated only slightly from an assessment from two years ago, according to a newly released state report.

And though that’s largely not terrible news, environmental watchdogs warn that a deeper dive into the data revealed more troubling issues for Pennsylvania’s streams: a net backsliding statewide in water quality and concerns about unknown cocktails of chemicals in the water.

Why does all of this matter?

Simply put, the mileage of streams that the report from Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection deemed to be “impaired” meant the water did not meet federal standards and were considered to be so contaminated or degraded as to pose a hazard to swimmers, canoeists and kayakers; to be too unhealthy to eat fish plucked from those waters; too polluted to drink; or were harmful to aquatic life.

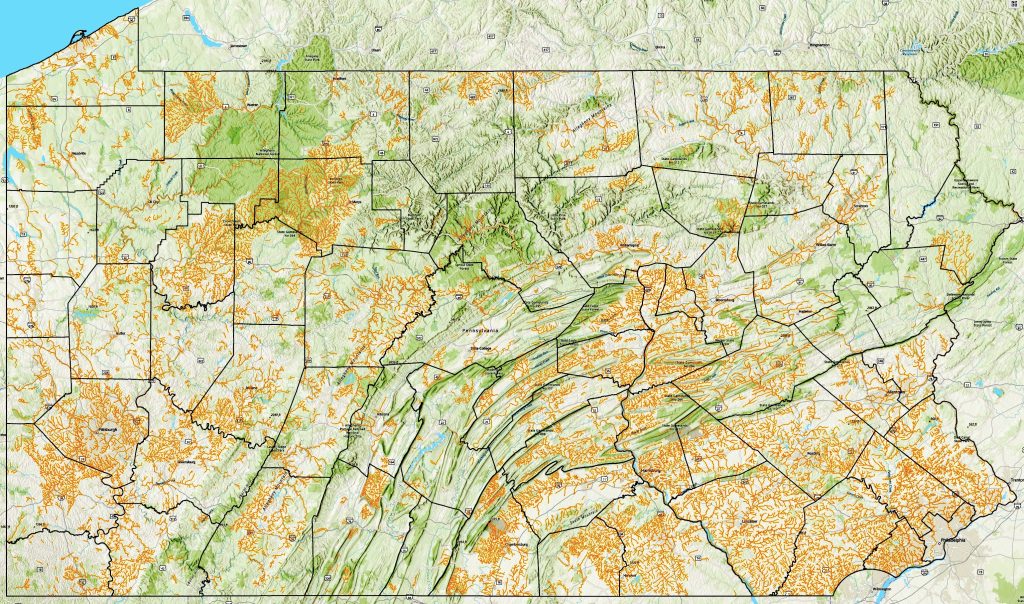

The health of these Pennsylvania streams is critical because the state boasts the largest land mass of the four-state Delaware River watershed.

Those waterways, which are in parts of 16 Pennsylvania counties, are the arteries that feed the Delaware, and polluted arteries can lead to a polluted river.

Think of it as the equivalent of having high cholesterol or an infection in the blood stream that could then affect the functioning of the heart. In this case, the Delaware River is the beating heart that supplies drinking water to more than 14 million people.

The river’s basin – made up of parts of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Delaware — is also a natural habitat for a variety of plants, wildlife and aquatic life, including more than 400 bird species and more than 100 species of fish. And as the world’s largest freshwater port, the basin is the generator of billions of dollars’ worth of economic activity.

In short, there’s a lot riding on the overall health of the river and the streams that feed it.

By the numbers

The revelations about the polluted streams are in the state Department of Environmental Protection’s 2024 Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Report.

It found that over one-third of Pennsylvania’s streams, or 28,820 miles, have “impaired” water quality. That figure is up from a 2022 report, which recorded 27,886 miles of impaired streams, making them unsafe for four specific uses: aquatic life, recreation, fish consumption or water supply.

Read more: Streams in the Delaware River watershed face a variety of threats

Of the 10,482 miles in the Delaware River watershed in Pennsylvania that were evaluated, 45.6 percent, or 4,904 miles, were deemed to be impaired, according to the DEP data.

That is up slightly from the immediate past assessment, which showed that of the 10,491 miles in the Delaware River basins that were assessed, 44.2 percent, or 4,751 miles, were impaired.

Of the nine sub-basins that make up the Delaware’s watershed in Pennsylvania, the heavily industrialized Lower Delaware unsurprisingly scored the worst, with nearly all of the stream mileage — 97.9 percent — found to be impaired.

Read more: 15 billion gallons of raw sewage yearly is released into Delaware River watershed, report says

The percentages of impairment in the other sub-basins that make up the Delaware River watershed were followed by the Crosswicks-Neshaminy basin (96 percent); Brandywine-Christina (76.2); Schuylkill (66 percent); Middle Delaware-Musconetcong (49.2 percent); Middle Delaware (26.6 percent); Lehigh (22.2 percent); Upper Delaware (10 percent) and Lackawaxen (.5 percent).

Those findings were either identical or virtually unchanged from the 2022 assessment.

Read more: Our special report on the findings of the 2022 water quality assessments

However, a notable degradation in water quality came in the Brandywine-Christina basin, where the number of miles of streams deemed to be incompatible with recreational uses jumped to 407 from 248, according to the DEP data.

SeungAh Byun, executive director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority, attributed that change to miles of the west branch of the Brandywine that had not been assessed before that were now included. She also noted that the area is heavily agricultural in use, meaning potentially more contaminated waste runoff.

“There’s a good chance you’re going to find E. coli in there,” she said.

The big takeaways

Emma H. Bast, a staff attorney with the environmental advocacy group PennFuture, noted that agriculture had overtaken acid mine drainage as a top source of impairment.

The DEP report found that, overall, the leading causes of impairment were: agriculture, acid mine drainage, urban runoff/storm sewers and atmospheric deposition.

“While the data confirm that many surface waters are maintaining their water quality, the overall number of streams that have been downgraded from ‘supported’ to ‘impaired’ is almost 10 times as high as the number of streams that have been upgraded,” Bast added.

She noted that riparian buffers, which trap pollutants and sediments that might otherwise reach streams, can help curb agricultural runoff. She cited a bill now being considered in Harrisburg (House Bill 1275, the Riparian Buffer Protection Act) that would help.

Scott Ensign, an assistant director at the Stroud Water Research Center, also endorsed the roles of buffers, citing the “significant role” that streamside forests can play in supporting clean streams.

“We’ve found that a 100-foot-wide riparian buffer on each side of a stream can reduce nitrogen, sediment and pesticides in the water running off farm fields, as well as provide other benefits that protect water quality and wildlife,” he said.

Streamside forests, combined with land management strategies that prevent pollution from reaching streams, “are the closest thing we have to a silver bullet,” he said.

Diana Oviedo Vargas, an assistant research scientist at the center, said the report accounted for pollutants that are fairly well known.

“However,” she added, “there are thousands of chemical pollutants contaminating Pennsylvania streams and rivers; this chemical cocktail requires more research to guide future monitoring and regulations. The majority of causes for stream impairment in this report fall in the category of ‘unknown.’ It is likely that these unknowns are at least in part related to the issue of the uncharacterized chemical cocktails.”

‘Clearly a lot of work to do’

Ensign noted that that since the last report, “there hasn’t been a net positive change, so there’s clearly a lot of work to do and efficiencies to be gained.”

“This is a call, more than ever, to rely on science to inform the best, most cost-effective strategies for restoration,” he said. “Solving these problems requires action and investment at every level of government; pure water is a right enshrined in the Pennsylvania Constitution, and it must be achieved.”

The DEP is accepting public comments and feedback about the report until Dec. 11. For details about to participate, click here.

This estuary is absolutely filthy and really nothing can be done to fix. I can remember when the Delaware had its own distinctive chemical odor near Eddystonr and Chester, when boat owners ha to use the C&D canal to reach the Chesapeake to prevent chemical damage.

The Canal is the perfect example of the difference in water quality. As to reach Chesapeake City, the water starts to mix and clear, until when you reach Old Town Point MD is is clear.

Shame on the EPA and PA for doing the absolute minimum to control it.