Mississippi’s creeping salt line: A lesson for the Delaware River

| September 25, 2023

What’s happening in the Mississippi River right now provides a real-world cautionary tale about the risks of salt water creeping upstream to threaten drinking water intakes.

There, as here in the Delaware River watershed, the flow of fresh water down river can usually be relied on to push the salt water back. Here, it’s the Atlantic. There, it’s the Gulf of Mexico.

Interesting to note that the minimum flow objective for the Delaware at Trenton is 3,000 cfs (cubic feet per second).

The minimum for the mighty Mississippi is a whopping 300,000 cfs.

Right now, that flow is measuring at 147,000 cfs, according to Ricky Boyett, chief of Public Affairs for the New Orleans District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and predicted to drop to 142,000.

The problem for that watershed is that the riverbed below Natchez, Miss., (which is about 280 river miles north of New Orleans), is below sea level, and that’s an invitation for the Gulf.

This is a problem that’s been encountered before, and one of the solutions is that the USACE builds an underwater levee (called a sill) to form a barrier to what Boyett called “the slow crawl” of salt water upstream.

He explained that salt water is heavier than fresh and so it crawls along the river bed. It’s also wedge shaped, so the “toe” of salt water can be as much as 15 miles ahead of the fat body of the wedge.

The USACE built that levee in July and today, Boyett said, it’s building it still higher.

New Orleans is about 90-100 miles upstream from the Gulf, but there are parishes near the Gulf that are already battling the salt.

Boyett said that local, state and federal agencies are all pitching in to help municipalities get the drinking water they need.

The USACE, for example, is going farther upstream where there’s no threat from the salt and bringing that water downstream in barges, where it’s used to dilute the salty water, bringing the salt content down enough so that municipal water treatment facilities can continue to supply drinking water to their residents.

In the Delaware River

As here, too much salt water can permanently damage the water treatment facilities.

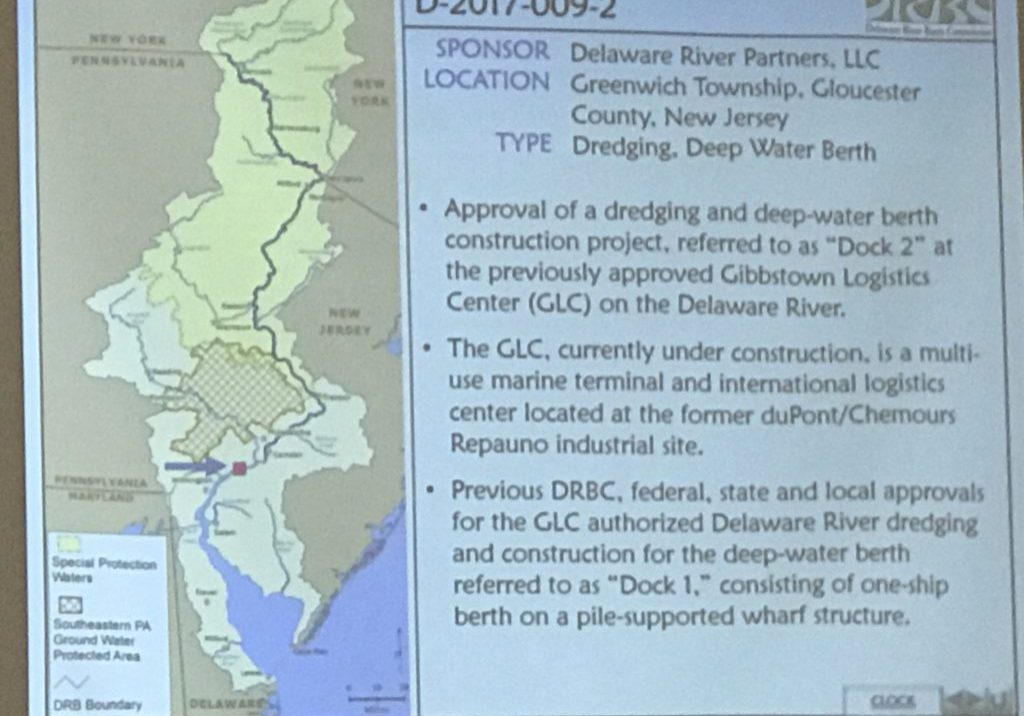

We haven’t faced this sort of crisis in the Delaware but the first course of action if the salt front moves too close to our drinking water intakes is for the Delaware River Basin Commission to call for water releases from Blue Marsh and Beltzville reservoirs to meet the Trenton flow objective.

And in the era of climate change, all possibilities must be considered as we’re predicted to have lots of water when it rains — as it has been doing the past few days — but the likelihood of droughts also increase. And a drought would mean less water to push back that salt water.

Here’s a link to the DRBC’s website, where the location of the salt front is mapped every day.

And here’s a link to a map, also from the DRBC, showing the location of the salt front during our drought of record in the 1960s.

For more information about the USACE’s efforts: https://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Releases/Article/3536186/usace-underway-with-sill-augmentation-to-delay-upriver-progression-of-saltwater/