Myths, mistakes and misconceptions about flooding

| August 24, 2023

Editor’s note: This is a free newsletter that was sent to subscribers. To sign up for the newsletters, email us.

In my last newsletter, we talked about ways to be “weather aware” through various alerts, social media accounts and websites.

Today, we hear from weather experts about myths, mistakes and misconceptions in dealing with flooding. But before we jump into that helpful advice…

A quick quiz

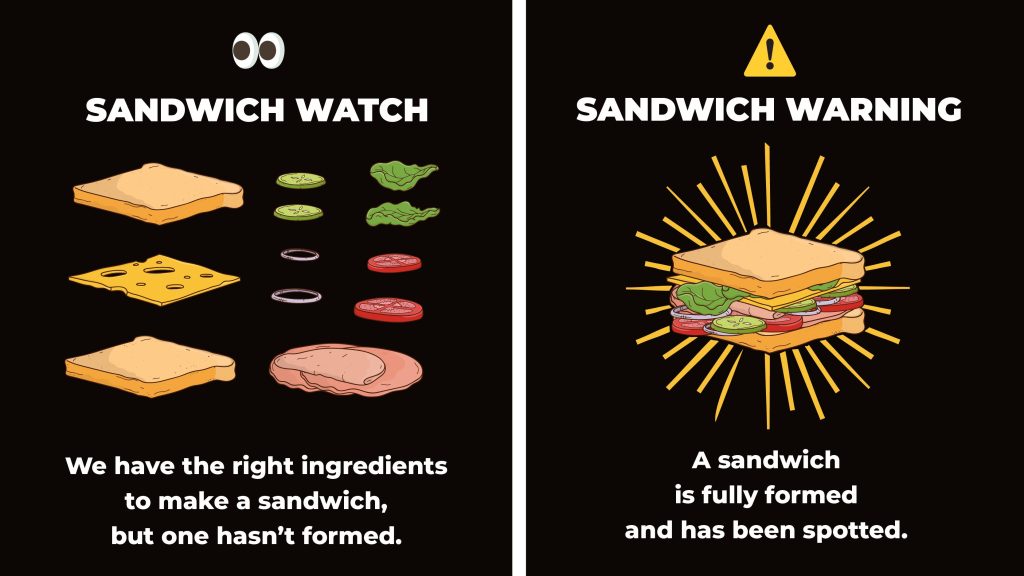

Do you know the difference between a weather “watch” and a “warning”?

You may see notifications about a severe thunderstorm watch, and maybe later, a severe thunderstorm warning.

The difference is that in the case of a “watch,” conditions are ripe for the potential of severe weather event, while a “warning” means it’s imminent or happening now.

Think of it this way:

Now, let’s hear from the experts about do’s and don’ts about flooding.

Mistake No. 1: Thinking it won’t flood here

Experts warned of being lulled into a false sense of security.

“Many people think that if they can’t see water from where they are, then they can’t flood. This isn’t true,” said Wesley Cheek, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Management at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

Cheek, who describes himself as a “sociologist of disasters,” described some low-lying or flood-prone areas as “sneaky.”

“You can’t really tell that you are in a dangerous area,” he said, adding, “Another issue that is coming up more and more is people who rely on past knowledge and say ‘Well, it never floods here.’ That may be true, but times are changing quickly. Places that didn’t flood in the past are now.”

Samantha L. Montano, an assistant professor at the Emergency Management Department at Massachusetts Maritime Academy, noted that climate change is altering rainfall patterns and many places do not have adequate drainage systems to keep up with intense rainfall.

“Combine that with an increase in development, paved-over green spaces, etc. and you have a recipe for increased risk,” she said.

Mistake No. 2: Underestimating flash flooding

“Flash flooding is REAL,” Duane Hagelgans, an associate professor at the Center for Disaster Research & Education at Millersville University in Pennsylvania, wrote in an email. “The power of the water is REAL. People die every year because they do not take flooding seriously. Roads and bridges have been swept away while people are in their vehicles on them.”

The understanding today of flash flooding — those deluges that can happen within hours or even minutes after an intense, heavy rainfall — are much improved from decades ago, said Ben Gelber, a meteorologist at the NBC television station in Columbus, Ohio, and a Poconos weather expert.

The rapid nature of flash flooding, especially when the ground is saturated, takes more lives in the U.S. than any other type of severe weather event, Gelber said.

“This requires paying attention to a roaring creek astride or beneath a roadway, which can rapidly overtake a vehicle,” he said.

He noted that the August 1955 flooding that took upwards of 100 lives in Pennsylvania “showed how a tranquil creek can turn into a raging river in a very short time,” adding that Brodhead Creek rose 25 feet in 30 minutes into a wall of water.

So, if you get alerts for a flash flood warning, pay particular attention. It might save your life.

Mistake No. 3: Thinking you can drive through it

In flash flooding events, “never attempt to drive through water if you can’t see the bottom of the road because you don’t know how deep it is, how swift the current is, or what’s going on below, such as a whirlpool or open drainage system,” Gelber said.

The oft-repeated warning — “Turn around, don’t drown” — exists for a reason.

Drivers get cocky, think they know better or underestimate the water ahead. People think that they can drive through standing water because they are in a heavy car and there’s only a “little” water, Hagelgans said.

And that’s when they get into trouble.

“Every year during flash flooding we have people that drive through a few inches of water and quickly become consumed by fast-rising water,” he wrote. “These people, if they are lucky, merely have their vehicle stall and they get rescued. If they are unlucky, they and their vehicle get swept downstream.”

He warned that people should never drive ahead on a road that appears to be have more than a normal rainfall, adding that only a few inches of rain can sweep a car away.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)