Flooding concerns spill over at Upper Delaware Council meeting

Delaware Aqueduct shutdown

| April 14, 2022

Rain is a fickle thing. The relentless thirst of New York City’s residents is not.

When you live in the path of the water that spills from the reservoirs, and they’re looking the way they did last week when the above video was taken, you can see why any fiddling with that water system could raise some alarms from nearby residents. Some residents experienced flooding last week, caused by the amount of rain we got.

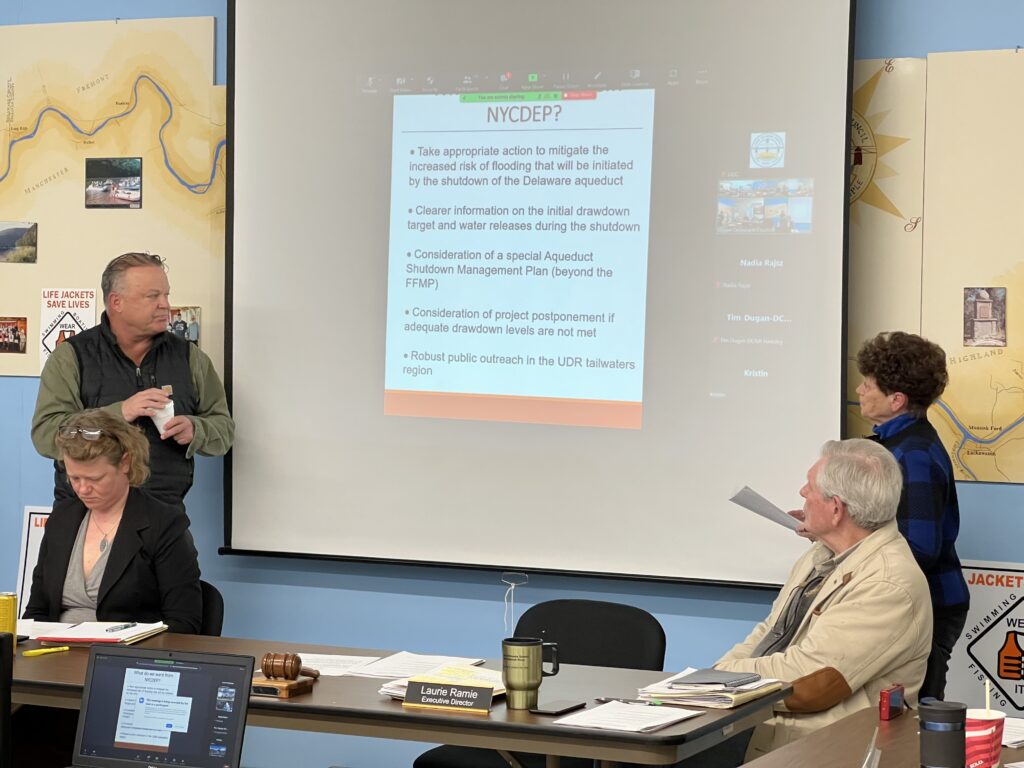

Which is why the Upper Delaware Council (made up of representatives of towns along the upper river — where the National Park unit extends from Hancock, N.Y., about 74 miles downstream) invited some people to talk about the summer shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct. More about the shutdown here.

Two people who have studied the river and have concerns about the shutdown spoke: Jeff Skelding, executive director of the Friends of the Upper Delaware River, who is also involved with the Upper Delaware Tailwaters Coalition, and Diane Tharp, executive director of the North Delaware River Watershed Conservancy (Nordel). Her concerns focus on flooding events a bit farther south though her analysis suggests more could be done at the reservoirs to alleviate the risk of flooding all over the basin.

But things took a turn away from an airing of concerns with the surprise appearance of a representative of those reservoirs, Jennifer Garigliano, chief of staff for New York City’s Bureau of Water Supply.

She had not been invited to the discussion but saw what was on the agenda and made it a point to show up to explain what the plan was, and to allay fears that there wasn’t any consideration for the fate of the down river communities in New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection’s plans for the shutdown.

She said that the fear of flooding spurred the NYCDEP to include that threat in its complicated matrix of decisions that need to be made and re-examined before, during and after the shutdown.

She reiterated a refrain by NYCDEP, which is that rain, especially storms, cause flooding — the reservoirs, by their very size, attenuate flooding.

You could probably translate that as: If the reservoirs weren’t there at all, the flooding downstream would be worse.

Tharp’s position is that the reservoirs ARE there and should be used to prevent catastrophe.

Garigliano’s position — and that of her bureau — is that the reservoirs are not a flood-control system but a water-supply system. The demands for water by NYC are paramount.

The NYCDEP has been working over the years to steady the releases it makes to allow for the flourishing of an exceptional cold-water trout fishery in both the tailwaters (just below the dams) and the upper river.

New York City’s DEP is a member of the Delaware River Basin Commission’s Regulated Flow Advisory Committee — though not a member of the commission itself. The commission is the governors of the four basin states and the federal representative, the U.S.Army Cops of Engineers.

The decree parties (note, different from the commission), which includes New York City’s DEP, have been working to revise, again, the complicated math and engineering for the Flexible Flow Management Program.

Part of that, for example, calls for varying the release of water from those dams according to how full those reservoirs are. If they’re low, it will work to ensure that there is still some water coming through to keep the branches and the upper river “watered.” In fact, they are responsible for maintaining a certain flow at a gage in Montague, N.J., stipulated by a 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decree.

One of the demands from some people south of the reservoirs is that the reservoirs should be kept less full — it’s called a void — at a constant15% void.

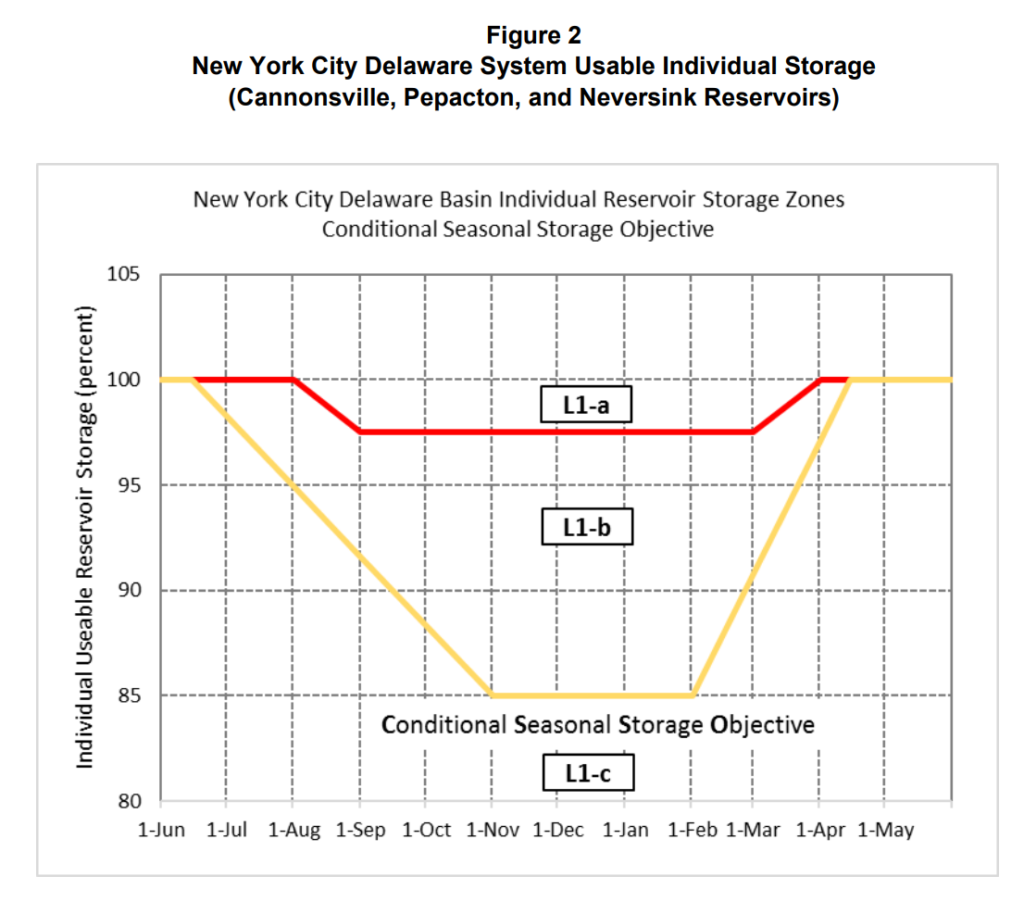

So looking at how full the reservoirs are, and that all three were spilling after our recent rain, we asked Garigliano if the waters now in the reservoirs were at the 15% void, which they sometimes are by agreement in the Flexible Flow Management Program. (Remember, how full the reservoirs are is affected by a complicated balance between the pretty predictable demands of NYC for water and the unpredictable amount of likely rainfall.)

Here’s her answer:

While it does sound easy (to answer if the reservoirs were at that 15%void before the rain)….it’s not. I’m going to point you to Appendix A of the 2017FFMP. If you look on page 13 at Figure 2 (It’s below) that outlines the Conditional Seasonal Storage Objective (CSSO). This is a storage curve for the reservoirs that shows what levels the water should beat for different times of the year. That 15% target is only from November 1to Feb 1 then we follow the curve and on April 15 the CSSO goes away and we maintain the reservoirs at 100% until the draw down period begins on June15 then we follow the curve down. If you look at the curve the void is only at 3% for this time of the year, not 15%.

The FFMP (Flexible Flow Management Program) also recognizes that maintaining the CSSO is not always possible because hydrologic conditions vary so much, which is why we also have the Discharge Mitigation Program as part of it. That program can be found on pages 21 and 22 of Appendix A. It essentially says that when we go above the CSSO the city will make discharge mitigation releases based upon whatever storage zone we are in. So NYC will make higher releases to get back down to wherever we are supposed to be on the curve.

I would also like for you to pay particular attention to page 22 where it calls out the different flood stages. Because I think (that’s) what a lot of people fail to recognize. In summary, when certain parts of the river are expected to flood, NYCDEP is required to reduce the releases coming out of the reservoirs. We make releases based on the rates in Table5, which are the drought releases rates. This way we are not making large releases and spilling. Once the river comes out of Action Stage, then NYCDEP will begin to increase the releases.

Here’s a link to the United States Geological Services (it’s in charge of monitoring the river)and the full FFMP document, and appendices, if you’re a glutton for more information!)

Garigliano ended her note with this: Just also a reminder that even when full, the reservoirs still attenuate flooding. Tharp said in an email that she welcomed Garigliano’s presence:

Since she was present, I felt more of an obligation to have her address our concerns from the viewpoint of the NYCDEP and to have her “fact check” so to speak what we were saying so as not to misrepresent the City’s position. Had she not been there, we would have made the same points, but it would have been from our interpretation of the meetings and presentations we had prior to this.

We really did not receive much new information from her, but she did say that our concerns are being heard and taken under consideration.

Tharp in that email raised the issue of the NYCDEP using a system of siphons to provide an emergency back-up drawdown system “in case of a wet year making it more important that drawdown capacities and a release schedule are sufficient to compensate for the additional 500-600 mgd (million gallons a day) that will stay in the reservoirs as well as the fact that inflows have typically been greater that out flows at maximum releases looking at the data from the last ten years.”

Garth Pettinger presented this data at the recent RFAC meeting and also urged the use of siphons for all the reservoirs, not just at the Rondout Reservoir where siphons will be installed to improve its discharge capabilities. The Rondout is where all the discharges of the three Delaware River reservoirs meet to begin the journey into the Delaware Aqueduct and to New York City.

At that RFAC meeting, Garigliano said the NYCDEP had reviewed using siphons at the three Delaware River reservoirs and decided that they were not likely to be helpful.

Also from an email, here’s Skelding’s view:

We are concerned about the increased risk of harmful flooding that may impact the people and communities below the NYC reservoirs during the aqueduct shutdown. The 500-600 million gallons per day of diversions from the reservoirs to NYC will be reduced to zero **on October 1, 2022**, thereby removing one important pathway for water to leave the reservoirs. Our research shows that, on average, annual inflows into the water sheds above the dams over the past ten years exceeds the discharge capacity of those reservoirs even with maximum water releases. That could mean sustained spillage over the dams, and flooding below the dams.

We request that the NYCDEP provide 1) more specific information on the drawdown capacities that will provide mitigation voids throughout the shutdown period, 2) the anticipated release schedule during the shutdown,3) a deferral plan for a wet year, and 4) a public outreach program.

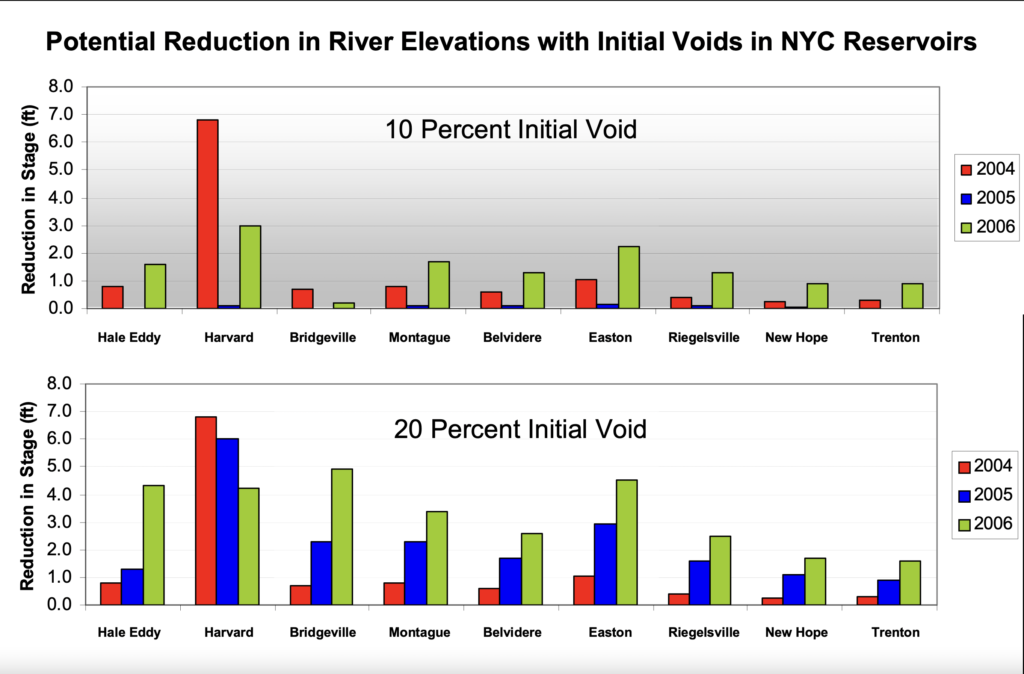

Looming over all these conversations is the experience of catastrophic flooding all over the basin in 2004, 2005, and 2006 caused by exceptional storms, though it might be appropriate to isolate downriver flooding problems from those near the reservoirs.

Here’s a link to the Delaware River Basin Interstate Flood Mitigation Task Force report, which concluded in 2009 that having a constant 15% void would not have reduced flooding.

Here’s the comment of then-DRBC Executive Director Carol Collier:

The results of the flood analysis computer model developed by a federal interagency team for the commission, as well as a review of inundation mapping and structural surveys prepared by the U.S. Army Corps of engineers, indicate that operational changes to reservoirs alone will not substantially reduce flooding if we experience storms similar to the three major events in September 2004, April 2005, and June 2006.

We believe the results support the earlier conclusion of the Interstate Flood Mitigation Task Force that no single approach will eliminate flooding along the Delaware River and that we must continue to focus efforts on implementing a combination of flood loss reduction strategies.

But Tharp wanted to point out that there was a section of that report which did indicate that there would have been a positive effect of 15 or even 20% voids. Here’s her email:

The chart below from the DRBC presentation shows that even though flooding would still have occurred in 2004, 2005, and 2006, the flood crests would have been reduced by feet in many locations.

In fact during the 2005 and 2006 flood if a 20%( or even a 15% void) void had been in the reservoirs my second floor of my home which is my living area would have not been damaged saving me $40,000 dollars in damages. So voids in the reservoirs DO make a difference and unfortunately this important finding from the Flood Analysis Model seems to be overlooked.

Of course, the wild card is that those studies reviewed models, accurate at the time, which did not reflect the unpredictable swings in weather we’re likely to see as we feel the effects of climate change.

![DC_Image [Image 4_Assunpink Meets Delaware] meets Delaware The Assunpink Creek on its its way to meet the Delaware River. The creek passes through woods, industrial and commercial areas and spots both sparkling and filled with litter.](https://delawarecurrents.org/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/DC_Image-4_Assunpink-meets-Delaware-1024x768-landscape-14f069364113da5e8c145e04c9f2367c-.jpg)