Group dowsing for money to water the Delaware Canal

The original job of the 60-mile Delaware Canal was to smooth out and speed up the delivery of coal from Northeast Pennsylvania to Philadelphia and the East.

Now, there's a new initiative underway that aims to smooth out the future for this 188-year-old relic of the Industrial Revolution. Back in the day, the canal was first and foremost a commercial enterprise and its care was part of the operating expenses of its owners.

These days, the canal is owned by Pennsylvania and operated by its Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and relies primarily on the not-very-deep pockets of the state's budget for its upkeep, which varies not according to the needs of the park but the ability of the state to pay.

"There's no way the state park's budget will ever be enough to provide first-class maintenance," said Allen Black, chairman of Delaware Canal 21.

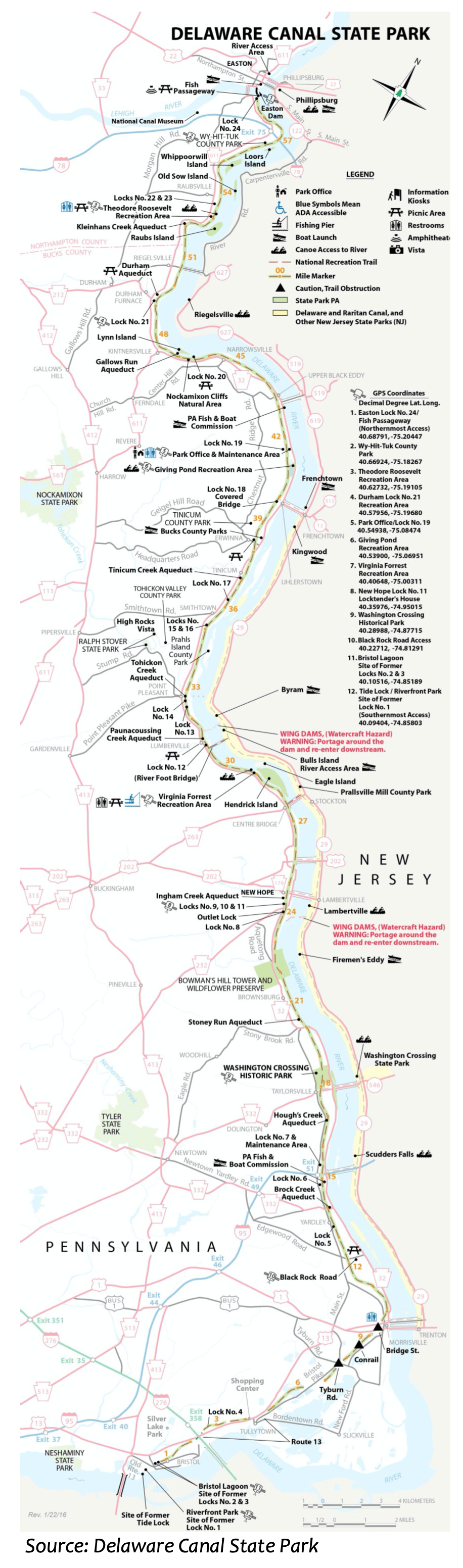

Delaware Canal 21 (delawarecanal21.org) has been organized to help the canal find a firm financial footing in the future and also to fully water the whole length of the canal, from Easton to Bristol, Pa. The Friends of the Delaware Canal (fodc.org) say that it is the last towpath canal in America capable of being fully watered and restored.

Getting it to that fully watered state is essential to the canal's survival. The canal is largely made of clay, and when there's no water, the impermeability of the structure fails, and it becomes incapable of holding water.

"Without water, it's just a dried-up ditch," explained Doug Dolan, Delaware Canal 21's executive director.

The goal of securing the canal's future just got a boost. The two counties that are home to the canal -- Northampton and Bucks -- have recently joined forces with Delaware Canal 21 and DCNR to begin a feasibility analysis to consider ways to better fund and maintain the canal, Dolan said.

"Everybody has ideas about the canal's future," said Dolan, "but at this stage we're trying our darnedest to keep a blank sheet of paper" because he wants to encourage all ideas to get presented. So far, those ideas range from tourist-focused businesses to low-head hydro-powered energy generation (the canal drops some 165 feet though 24 locks).

The work of the new alliance is not just about the canal; it's understanding that the canal is affected by the land (and the river) adjacent to it and subject to too much or too little water.

The Delaware Canal wasn't built for flood or drought control -- it was a commercial enterprise, explained Devin Buzard, DCNR's manager of the park.. Adding to the complexity, the landscape that surrounds it has radically changed since the 1830s. With increased development comes stormwater problems.

The Delaware Canal has its own watershed, even though it's next door to the Delaware River. The Delaware Canal 21 website refers to the 40,000 acres that surround the canal and drain into it as a "stealth watershed." The DCNR has little control of those acres.

In 2017, Delaware Canal 21, with DCNR and other state agencies and some financial help from the William Penn Foundation, completed a stormwater study of the canal.

So now, in addition to the state, the William Penn Foundation has helped fund seven projects to relieve some stormwater impacts in the short term while longer-term ideas are hammered out. (See map)

But the idea of partnership isn't new to this neck of the woods.

The canal park is also part of the Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, which includes the National Canal Museum and stretches of the Lehigh, which was part of the water "highway" for coal from the Upper Lehigh regions.

Here's its site: https://delawareandlehigh.org

Here's how Buzard explains the connection: "We do work closely with them as we are a part of the National Corridor and they support our operation in a multitude of ways to include: volunteer efforts, funding, resources, and advocacy just to name a few."

A similar relationship exists between the Delaware Canal State Park and the previously mentioned Friends of Delaware Canal (fodc.org), which lends muscle to its support of the park, like painting bridges and repairing rock walls.

Most recently the Friends raised $78,000 to repair one of the canal's historic camelback bridges.

Check out the canal's website for more information: https://www.dcnr.pa.gov/StateParks/FindAPark/DelawareCanalStatePark

If you need your appetite whetted for a visit, the 60 miles of the park are chock-a-block with nearby parks, like the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park in New Jersey; Ringing Rocks National Natural Landmark in Pa.; designated National Register Historic Districts like New Hope, Pa., and Frenchtown, N.J.; and the canal -- a National Historic Landmark -- passes the site of Washington's crossing of the Delaware in 1776.

This just in:

https://patch.com/pennsylvania/newtown-pa/former-david-library-property-become-public-green-space

What an outstanding summary of the challenges facing the Delaware Canal and DC21’s efforts to help DCNR to find new funding to re-water the canal. Well done Meg McGuire.

Boyce Budd

Member of DC21 Board of Directors

Former Tinicum Supervisor