A potpourri of problems for scientists in the Delaware River and Bay

Microplastics are a hot topic in the Delaware River and bay.

"More people are calling me about this issue than anything," said Ron MacGillivray, senior environmental toxicologist at the Delaware River Basin Commission. Microplastics are small pieces of plastic less than 5 mm long (about the size of a sesame seed).

Here's a quick explainer video from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Below you can see two slides that explain what the DRBC is studying and where.

Microplastics came up at two separate Delaware River Basin Commission advisory committee meetings last week, but both were references to a study that the DRBC is tackling.

Here's the DRBC page on microplastics

Jacob Bransky, an aquatic biologist said we're still in the early days of discovering what sort of problem we have, if any, with plastics in our watershed. One of our local national parks -- the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River -- began its microplastics study in summer 2018, working with the United States Geological Survey. There are also studies being conducted by the University of Delaware, Philadelphia Water Department and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Harmful bacteria from sewer overflow

Another growing concern is an off-shoot of some very positive developments -- we are getting more interested in the river. While people taking a dip in most of the river is perfectly fine, there are some areas -- or times -- when that's not a great idea. The first, people IN the water, is called primary contact, the second is, not surprisingly, secondary contact. And the place where this can be a problem is in the most urbanized part of the river, especially Philadelphia.

The slide below gives details of a study that the DRBC is launching to study the problem:

And that's because Philadelphia, like many old cities, has a wastewater treatment system called a Combined Sewer Overflow: When the usual sewers receive too much stormwater, those stormwaters can flood the wastewater treatment system, which can result in waste going directly into the river.

Not good for primary contact. More and more, people are getting up close and personal with rivers, doing paddle board yoga or jet skiing, which can mean a dunking in the water.

Philadelphia has developed an easy way to let people know about one of its rivers -- the Schuykill --called Rivercast. Find out more here.

The Delaware is a little more complicated and PWD has CSOcast to alert river users of possible contamination in specific sites.

The DRBC has been monitoring bacteria levels in the Delaware River and Bay for ages. But most of that monitoring has been out in the middle of the river. There's a new study underway to study those levels closer to shore, where the sewer outflows are, and where the people are.

"It's not just bacteria levels that we should be concerned about," said John Yagecic, manager of the DRBC's water quality assessment team. "This is a busy river, and it's dangerous to be out on the river in a kayak or canoe when there are giant ships up and down the river."

Microplastics and sewer overflow were just some of the topics discussed at the STAC/MACC annual meeting Monday, June17, 2019

I know, more alphabet soup courtesy of the DRBC, once again hiding science under a plethora of nomenclature.

To break it down: This is an annual get-together of two scientific powerhouses of the Delaware River: the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary's Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee and the DRBC's Monitoring and Coordination Advisory Committee.

The Partnership (PDE) is recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency as what you might call the chief custodian of the Delaware Bay in its National Estuary Program, formed to protect and restore the water quality and ecological integrity of estuaries of national significance. The Delaware is one of 28 in the whole country.

Translation of all that? Lots of science.

So every year the scientists in both agencies, as well as municipal, state and federal partners, academics and environmental advocates get together to let each other know what they're up to.

The PDE is intensely interested in bivalves because of their remarkable ability to stabilize shorelines and to clean water. Check out Living Shorelines and Freshwater Mussels and Oysters.

The DRBC focused its presentations on its nutrient (like nitrogen and phosphorus) monitoring in the river and bay. You only need small amounts of each -- too much can provoke problems like causing excessive plant and algae growth, called eutrophication.

You can have a look at the presentation here.

Right now the DRBC is involved in an intensive modeling exercise to ascertain how much dissolved oxygen is in the river, how that affects the young of sturgeon, an endangered species and how much the wastewater treatments plants on the river contribute to the problem.

Hydrologists Jeff Fischer and Heather Heckathorn from the United States Geological Survey, New Jersey Water Science Center, provided an update to the suite of water monitoring stations that are being installed, enhanced, and/or proposed throughout the entire Delaware River Basin. This is from its website:

In fiscal year 2018, the USGS selected the Delaware River Basin as a pilot for implementing the nation’s next-generation (NextGen) integrated water observing system to provide high-fidelity, real-time data on water quantity and quality necessary to support modern water prediction and decision support systems for water emergencies and daily water operations.

More info here.

Next up, on Tuesday, June 18, the Toxics Advisory Committee, which heard from scientists about their monitoring of PFAS in fish, surface water and sediment. Here's an EPA page for more information.

PFAS investigations

The gist of what the three scientists -- Sandra Goodrow from NJDEP, Jessie Becker from NYDEC and Ron MacGillivray from the DRBC-- were saying was that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are ubiquitous in our air and water, and they need much further study to ascertain what levels are safe for humans. Also, there are many different sub-groups of chemicals that fall into these categories and some of them bioaccumulate, which means bodies -- of fish, animals or people -- can hang on to the chemicals causing what might be as yet unknown problems down the road.

There are three sets of slides:

Investigation of Levels of Perfluorinated Compounds in New Jersey Fish, Sediment and Surface Water, presented by Sandra Goodrow, from NJDEP,

PFAS in New York State Fish 2010-2018, presented by Jesse Becker, from NYSDEC,

PFAS in Surface water, sediment and Fish from the Delaware River presented by Ron MacGillivray from DRBC

On Wednesday, June 19, the Subcommittee on Ecological Flow met. You can find out what it's up to in a previous story from Delaware Currents here. But this committee is trying to find the best possible flow for the upriver ecosystem. Remember, although the main stem Delaware is undammed, the headwaters are captured in New York City's reservoirs. And how much water they release and when is crucial for all the critters (human and otherwise) that live north of Port Jervis, N.Y..

Yes, it was a pretty packed week for advisory committee meetings, but they are usually more interesting than the full DRBC meetings. The advisory committee is all about the science, the full commission meeting is more politics, which isn't surprising. It is charged with creating policy for the river.

Anyway, one more advisory committee meeting.

Water Management Advisory Committee, Thursday June 20, 2019.

All the advisory committees have their work cut out for them, but this one is pretty tightly focused on a big problem for the future that the DRBC, the states, the federal government and many of the water supply systems -- both public and private -- are concerned about: Will we have enough water?

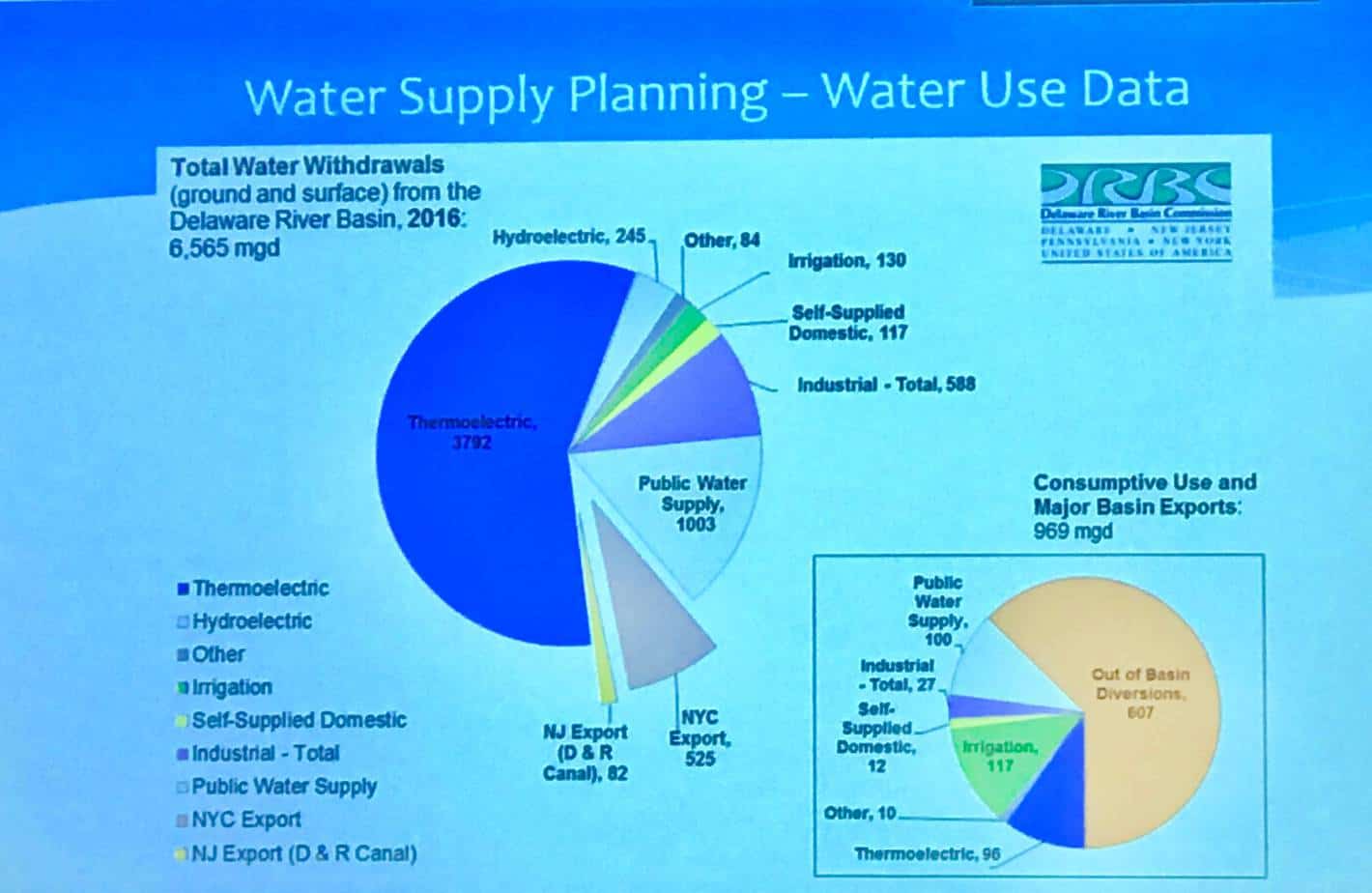

The photo below (from a DRBC slide) shows how we used Delaware River water -- in 2016.

Questions about how much we use, how much we waste and the interplay between groundwater (the water underground) and surface water (the water we see in lakes, rivers and streams) are all intrinsic to our water supply today and tomorrow.

Fracking study misrepresented

The committee also heard from Dr, Gerald Kauffman, director of the University of Delaware's Water Resources Center. He said he was concerned that a report he wrote in 2011 that gave the potential dollar value of fracked gas in the watershed is being misappropriated by some in the Pennsylvania Legislature's ongoing battle over bringing fracking to the Delaware River basin.

And also, the move might be a way to prevent the possible fracking ban in the watershed by the Delaware River Basin Commission. By viewing the ban as a "taking" by the commission, it would make the commission liable for payments to landowners denied the profits of allowing fracking on their watershed property.

The dollar value for the natural resources of the watershed he gave back then was $3.3 billion annually, part of the $25 billion for the whole watershed in this report: Socioeconomic Value of the Delaware River Basin in Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, (2011) which you can find here.

An updated report (2016) here.

That value is now much smaller, Kauffman said, since the area where shale might be profitably extracted from is much smaller as the industry got drilling, extending further to the west and south.

Here's a recent map from Penn State's Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research that shows the number of wells drilled by year.

The point for Kauffman is that the value of clean drinking water can't be overstated. Breaking down in current dollars: clear drinking water ($2.8 billion), healthy forests ($4.0 billion) and recreational opportunities ($950 million): a total of nearly $8 billion. The previous report included other aspects of value in the watershed like agriculture and the river's ports.

"What is clear is the value of clean drinking water -- the four governors have recognized that," Kauffman said in an interview held after the meeting.

"The energy/water nexus has always been difficult to balance, as the Tock Island plan to build a hydropower dam in the Delaware in the 1950s and 60s shows.

"The Delaware River Basin Commission does a great job of balancing all the competing interests," he concluded.