19th-century bridge’s wooden planks carry 21st-century commuters

THE RUMBLE OF THE WOODEN PLANKS of the Dingmans Bridge is the audible welcome mat that Pennsylvania lays down for the city slickers of New York and New Jersey, driving west over the Delaware River.

It’s a skinny bridge, so going slowly — as the sign suggests — is a really good idea!

And the price is right: $1 per crossing, and the tolls are taken by a real live human.

Most days the exchange is accompanied by a cherry “Good morning,” or “Drive safely.”

Very different treatment from the harassed toll takers at most interstates.

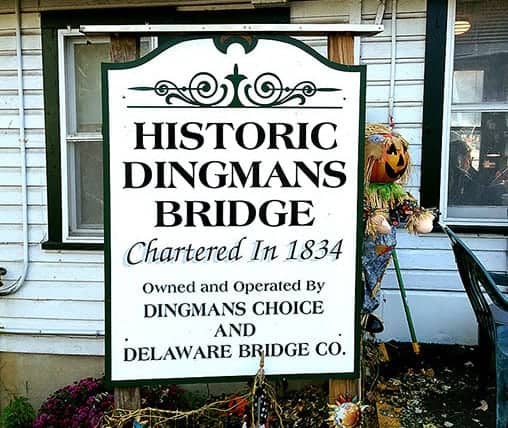

This throwback is brought to you by the Dingmans Choice and Delaware Bridge Company, whose vice president, Alan Shook, is proud of the bridge and his family’s involvement with it.

“My great uncles bought the charter from the Dingmans family in about 1898, and this bridge was built in 1900 with the first toll taken in November 1900,” Shook said.

Alan Shook's family bought the charter to Dingmans Bridge in 1898.

It’s not the first bridge that has been built on this spot. Three others were washed away, blown away or fell apart. In fact, as the name of the Pennsylvania community might suggest (Dingmans Ferry), there was a ferry here. The first was in 1735, when Andrew Dingman chose to build his house on the Pennsylvania side of the river.

Shook noted: “This was the western wilderness then.”

It was Dingman’s choice to live here on the western banks of the Delaware and that’s the reason that the first name of the community was Dingmans Choice.

His heirs got a charter from the state to build the first bridge in about 1836, and when that was washed away, there was another bridge built in 1850, and that lasted in a deteriorating state until the late 1850s, when it fell apart.

“Commuters,” such as they were back then, lived with the ferry once again through the late 1890s until this bridge was built and it’s been servicing traffic ever since.

It used to be that the noteworthy wooden planks that give this bridge its distinctive rumble were turned over in a semiannual ritual that marked the changing seasons. Now, the individual planks have given way to pre-assembled boards that are removed once there’s any sign of wear.

That’s what the crew was doing last week when the bridge was closed for a few hours in the middle of the day. It’s a precaution — to insure that the planks stand up to the wear and tear of a Northeast Pennsylvania winter. Usually there’s a fairly rigorous inspection of the bridge and its wooden panels every June.

“They crawl underneath and rattle every board,” said Shook. It’s an annual process that’s been going on ever since 1980, when the bridge owners finally realized the bridge was here to stay. Until then, this bridge, like countless homes up and down the Delaware River Valley hereabouts, was aimed to be underwater at the completion of the Tocks Island Dam, proposed by the Army Corps of Engineers, and opposed by most of the local citizenry.

The dam would have created a huge lake from the Delaware Water Gap to Milford, PA., to alleviate flood problems, supply water for New York City and Philadelphia, and supply hydroelectric power. Plans for the dam predated the locally disastrous flooding of 1955 and continued until it was finally vetoed by the Delaware River Basin Commission in 1975. The area that was seized for the project created the backbone of today’s Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.

Until the project was shelved, the future of the bridge looked shaky. Once that shadow passed, the owners of the bridge began an intensive renovation project in 1980. The engineers they used — Hartman Engineers of Buffalo, N.Y. are the same engineers that inspect the bridge these days.

“We’re very careful of the upkeep of the bridge. We have private liability for it. There’s no government backing here. Our inspections of that bridge is more rigorous than the law requires,” insisted Shook. This is one of the few private bridges in the United States.

The bridge has that solid utilitarian style you’d expect from easy 20th century, no-nonsense builders. And its superstructure has withstood the test of time. Most of what you see is the vintage structure. “What you don’t see (underneath)” said Shook, “is modern steel.”

Dingmans Bridge is a truss bridge, with the signature triangle shapes above the bridge bed to “carry” the weight of the planks. Shook explained that you could imagine the bridge as a sort of bow with the superstructure forming the arc of the bow, and relatively thin steel rods as supporting “strings” underneath the bridge bed.

Some of the uprights still carry the mark of their maker: Phoenix Ironworks 1862.

“It’s in as good shape today as it was back in 1900,” said Shook.

The repairs are done before rush hour, and traffic starts the telltale slow rumble.

The bridge is ready for winter.