Winter Salt Week highlights challenges to curbing road salt use in the Delaware River basin

| January 27, 2025

For wintertime drivers who expect clear roadways with near-blacktop conditions, a slow-moving salt-spreader spraying grayish granules from its spinning plate can be a welcome sight.

Though such trucks and their payloads work to minimize a hazard — motorists sliding off slick roads — they also pose a hazard of their own: harming the environment and human health through the overuse of road salt.

There’s a growing awareness of how road salt applied to streets, sidewalks and parking lots can pollute lakes, streams, and drinking water, corrode roads and bridges, and pose dangers to people who have sensitivities to salt.

Public service campaigns, like the Stroud Water Research Center’s “Cut the Salt” effort, have started to sink in, said a center spokeswoman, Diane Huskinson. “It’s working because people are becoming more aware,” she said. “We’re hearing from random folks who say, ‘I didn’t salt today.’”

The effort to reduce the use of winter salt is crystallized in a larger nationwide campaign, Winter Salt Week, which kicks off today that will draw participants throughout the Delaware River watershed.

Why it matters

Organizers of Winter Salt Week estimate that 20 million to 30 million tons of road salt are used each winter. That’s the equivalent to the weight of 175,000 blue whales or 62,000 passenger airplanes.

The significance of the overuse of salt is that it does not go away. It dissolves and moves with water into streams, rivers and even into groundwater.

Coming Thursday to Delaware Currents: Road salt is a year-round groundwater contaminant

Past research done by the Stroud center has found some water sample tests came back with salinity measurements as high as what would be found in the ocean, Huskinson said. “There are real, direct human health impacts,” she said. “Whether people realize it or not, it has an impact on their lives.”

How?

- More of your money, some in the form of your tax dollars, has to be spent to fix the corrosive damage done by salt. The cost of vehicle and infrastructure damage and extra road maintenance is estimated nationally to be more than $60 billion each year, according to Winter Salt Week organizers.

- If you are an outdoors enthusiast, an angler or a birder, take note because high chloride levels from road salt can harm aquatic life and habitats.

- For people who are on salt-restricted diets or have sensitivities to salt, excessive salt seeping into their drinking water can be harmful.

- It’s not unheard-of that homeowners have had to rely on bottled water or install expensive filtration systems after their private wells were poisoned by road salt that worked its way into groundwater systems that feed their water supply.

- Salt, as it’s sprayed and scattered through the air, can fall on plants and grass, leaving vegetation with salt burn.

Elaine Panuccio, a water research scientist at the Delaware River Basin Commission, pointed out the damage that salt can do to municipal water treatment facilities.

“Increasing salts (in particular, chlorides) can corrode pipes and cause the leaching of metals (of specific concern are lead and copper from older systems) as chloride is a persistent and highly corrosive ion,” she said in an email. “Additionally, older homes may have lead pipes that can be at risk of corrosion from salty water.”

‘Hiding in plain sight’

Stephanie Uhranowsky, the executive director of the Brodhead Watershed Association, attributed the explosive use of road salt to increased development, changing expectations about how much paved surfaces should be snow- and ice-free, and growing concerns about liability from slip-and-falls. She cited, for example, a New Hampshire study that found that parking lots accounted for half of the road salt usage.

She said it’s easy to spot pollution or contamination when it’s readily visible, such as litter or debris along a roadside or a chemical spill, but noted that “salt has its way of hiding in plain sight.”

“We expect to see it there in winter just as we do snow,” she said in an email. “And we don’t often stop to consider how much is too much. Salt comes with an invisible impact, one not easily seen or acknowledged when the snow melts and the salt washes away. Out of sight, out of mind.

“To the naked eye, salt seems to disappear,” she continued. “But it doesn’t. It’s absorbed into our rivers, streams, and creeks, it seeps below the surface and infiltrates our groundwater, it makes its way into our drinking water and private wells, and ultimately, it flows downstream. It also accelerates the corrosion of pipes and vehicles along with the erosion of critical infrastructure.

“However, these issues can often go unnoticed simply because we aren’t actively looking for them or fail to recognize their significance until the damage — such as the harmful effects of salt pollution — has already been done. That’s why community awareness and the encouragement of best practices when it comes to mitigating winter salt pollution are so important.”

Monitoring efforts

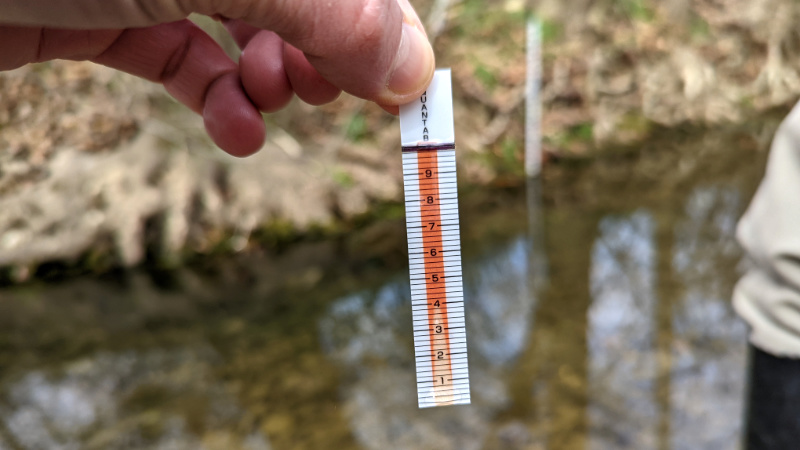

The Watershed Institute is the New Jersey representative to the national Winter Salt Week initiative. The institute hosts NJ Salt Watch, a volunteer water monitoring project that is still accepting new volunteers. For the institute’s current volunteers, it will be wrapping up Winter Salt Week on Friday with a statewide snapshot, according to Erin Stretz, the assistant director of science and stewardship at the institute, which is in Pennington, N.J.

“Our goal is to gather as much data as we can during a single day, and during similar weather conditions, so we might discern how chloride levels change with differences in regional road salt application rates,” she said.

Stretz is also giving a road salt talk for the Delaware River Greenway Partnership’s Heritage Lecture Series on Feb. 11, entitled “Drains to River: The As-SALT on Our Freshwaters.” Sign up here.

The Delaware River Basin Commission has also been monitoring the various effects of salt on the basin.

“Studies suggest that chloride concentrations in winter are as much as a hundred-fold over summertime levels,” according to the commission, which added that higher chloride concentrations are connected to the presence of impervious surfaces, such as parking lots.

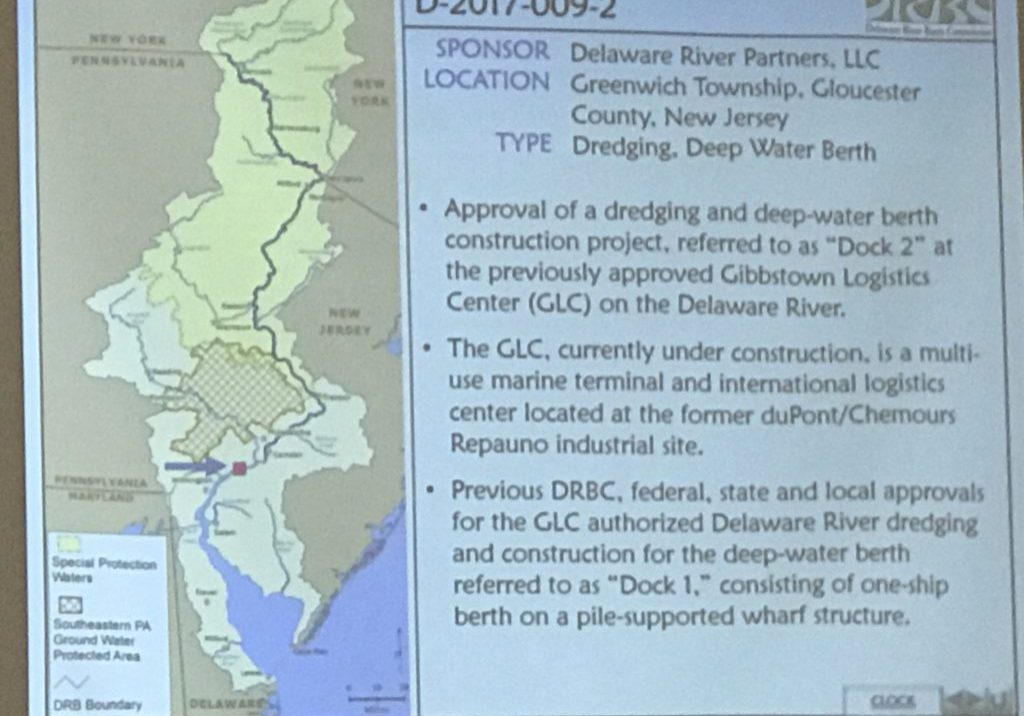

Elevated chloride concentrations have also been a concern in the non-tidal Delaware River, which are protected under the DRBC’s Special Protection Waters regulations. A commission spokeswoman, Kate Schmidt, said the DRBC is working to understand and address freshwater salinization, specifically within Special Protection Waters.

A study was conducted from 2021-23 and next steps are being developed, she said. Further, DRBC staff members plan to monitor chloride levels in the river this winter, especially as thawing occurs.

“Over the past several years, instream monitoring of the non-tidal river has shown an upward trend in chloride concentrations,” the commission said on its website. “While concentrations are still below criteria for drinking water and aquatic life use, the DRBC is watching this trend closely.”

In 2022, the commission formed the Salinity Impacts Freshwater Toxicity Workgroup to sift through the escalating issue of freshwater salinization and increasing chlorides in rivers and streams and discuss regulatory and road salt management options.

Winter Salt Week testing and events

The Stroud center for the first time will participate in Winter Salt Week, which kicks off today with a series of webinars. For more information and to register for the webinars and the stream sampling, check out the Stroud Water Research Center’s Winter Salt Week list of events.

- 1:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. on Monday: “An Eye on Salt Pollution”

- 1:30 p.m. on Tuesday: “Dilution is NOT the solution.”

- Various sessions from a public works perspective will be offered on Wednesday from state and local agency staff from Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Virginia and Wisconsin.

- 1:30 p.m. on Thursday will feature a policy solutions panel and a 30-minute lightning round of presentations followed by a question-and-answer period.

On Friday, Jan. 31, the Stroud center is hosting water sampling at more than 100 sites in the West Chester, Pa., area. The center has about 25 partners across the Delaware River Basin and Pennsylvania that will also be engaged in sampling, leading to at least 250 sites being tested.

Stroud center officials anticipate having a data entry system up and running so that results will be available in real time through an online map.

How you can help

Some tips from the Brodhead Watershed Association and DRBC:

- Shoveling snow early can prevent ice from forming and minimize the need for salt.

- Always shovel before applying salt.

- A little salt goes a long way. Excess salt will not melt snow any faster.

- Sweep up any excess salt to prevent it from entering storm drains.

- Bear the temperature in mind. Traditional salt is only effective above 15 degrees.

- For those with a wood burning fireplace, ash absorbs sunlight and will help melt ice quickly on a sunny day.

- Follow #cutthesalt on social media for updates and helpful tips.