Wastewater treatment plants: problem and solution for a healthier Delaware River

Second in a series: dissolved oxygen and the Atlantic sturgeon

Yes, "Serge" has a problem -- or rather his kids do. When sturgeon are young they need higher levels of oxygen dissolved in the water they swim in than the older, adult sturgeon. More than that, the Atlantic sturgeon is a standard bearer for a healthier river: Measuring the dissolved oxygen in the water is one of the litmus tests for how water quality has improved.

OK, now you've got a handle on the problem: There is too little dissolved oxygen in the lower Delaware River and Bay for the young of an endangered species (the Atlantic sturgeon) to thrive. And too much ammonia is the cause.

Here's a conundrum: the wastewater treatment plants of the Delaware have been improving their discharges over time (with due credit to the DRBC) and can claim that one of the big reasons the water is cleaner now is because of its efforts. But it's likely that those plants in the lower river and bay are a significant source of the dip in dissolved oxygen since reducing the ammonia in their discharges to the river has not been a top priority, until now.

Ah-ha! Have we found the villain(s)? Those wastewater treatment plants?

Big dischargers

Well, different people offer different answers to that question. Dedicated readers of Delaware Currents will recognize that in most cases where the river is having a problem, the reasons are complicated and pointing fingers and assigning blame don't necessarily get us to the place where difficult problems are solved.

But it is true that the 12 top dischargers (referred to by the DRBC as Tier 1 dischargers) are a big part of the problem.

"The Tier 1 dischargers are estimated to contribute 95% of the incremental cumulative load of ammonia, total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), and 5-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) from point dischargers,(his emphasis)" said John Yagacic in an e-mail. He's the DRBC's manager of Water Quality Assessment and also its point person for the advisory committee that is working on this issue, the Water Quality Advisory Committee.

Let's clear something up -- point dischargers are specific points of discharge to the river. Yagacic explained, "These pollutants also come from other sources, such as tributaries, which were not included in this computation for defining the Tier 1 dischargers."

There are 12 wastewater treatment plants in the Tier 1 category -- all municipal wastewater treatment plants:

- PA Philadelphia Water Department, Southwest

- PA Philadelphia Water Department, Northeast

- PA Philadelphia Water Department, Southeast

- PA Lower Bucks County Joint Municipal Authority

- PA DELCORA (Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority) DELCORA is in the middle of a purchase by Aqua Pennsylvania, which will make it the largest wastewater treatment plant in the watershed not operated by its municipality.

- PA Morrisville Borough Municipal Authority

- NJ Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority

- NJ Gloucester County Utilities Authority

- NJ Hamilton Township (Mercer County) Water Pollution Control Facility

- NJ Trenton Sewer Utility

- NJ Willingboro Municipal Utilities Authority

- DEL City of Wilmington Department of Public Works

All of these have been identified by the DRBC as significant contributors to the dissolved oxygen problem (there's also a Tier 2) and they are all our municipal wastewater treatment plants. All of them spend our money to get our waste cleaned up for the next intake of water supply to yet another municipality. Remember that Archimedes screw image from the earlier story? What is discharged upriver, gets picked up as our drinking water source downriver.

So, who are the villains now?

Considering the costs

Those wastewater treatment plants are dealing with our excreta. Will we "allow" wastewater treatment plants to bust budgets to find and implement solutions? Those improvements won't be cheap. I can imagine quite a few elected officials facing taxpayer anger that our hard-earned dollars are going to protect a fish. Really though, it's about making the river healthier.

Some of you might be ready to spend for such a cause, but others might not. Some might be pleased to know that their municipality isn't eager to spend their tax dollars cleaning up their waste if their waste contributes less to the dissolved oxygen problem than another waste-treatment facility.

In other words, at issue for these plants, these municipalities, these taxpayers (you and me) is: What sort of money would a plant need to spend to get its treatment system fixed to solve what it would consider its appropriate share of the dissolved oxygen problem, to get it in line with state and federal standards?

The top contributor to the problem (for a variety of reasons we'll talk about later) is the Philadelphia Water Department. It is already moving ahead with a plan to take care of some of its ammonia problem that has an early-estimated price tag of $40 million.

Important to note here, the PWD is not just waiting the results of the DRBC modeling efforts to start its ammonia-reduction effort.

Even while the model is still being built, the DRBC has commissioned Kleinfelder -- a science and engineering contractor -- to help determine the costs of improvements for the various plants.

And the Water Quality Advisory Committee, which is responsible for finding solutions to the dissolved-oxygen problem, has sent letters to the various plants, asking if there are short-term modifications that can be implemented that might have some impact on the ammonia problem.

So the DRBC's theory is that slow-walking a costly increase in oxygen standards might mean some savings for residents who rely on the top ammonia producers. An old adage comes to mind: Slow and steady wins the race.

PCB: the past as prologue

Remember, though, what the Delaware Riverkeeper Maya van Rossum said: "We don't have the luxury of time." And the victim might be the sturgeon and, in turn, the extinction of a species.

An expert in our local sturgeon population, Dr. Dewayne Fox, fisheries professor at Delaware State University, was asked about the imminent demise of the Atlantic sturgeon:

"The question of 'imminent:' There has undoubtedly been a loss of genetic diversity and that is well beyond my comfort zone. Do I think we will completely lose Atlantic Sturgeon in my lifetime?- No but but I do think when you look at the loss of our unique genetic strain (haplotype) that this is possible," he concluded.

There is a balancing act because the DRBC isn't wrong about the possibility of a negative reaction by dischargers. Years ago, the DRBC moved to act on the presence of PCBs in the river.

According to Andy Kricun, chief engineer for the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority, the DRBC -- at the request of three states and the EPA -- recognized that the PCB problem in the river needed to be addressed. The wastewater treatment plants already had a relationship with Manko Gold, and the group reconvened to discuss the problem.

Van Rossum remembers that process as being very contentious: "This issue (on DO sag resulting from the treatment plants) is like the process of cutting back on PCBs in the river. That was one of the earlier, maybe the first where the waste dischargers grouped together and enlisted Manko Gold.

"There, like here, they (the dischargers) didn't want to focus on how they could be part of the solution, rather they wanted to reframe the problem and even question that there was a problem.

"This is a repeat battle of PCBs: Exactly, exactly, exactly."

But maybe not. The dissolved-oxygen issue concerns municipal waste water treatment plants, as did the PCBs, but that also included larger industrial dischargers, businesses reluctant to spend money. Kricun saw the wastewater treatment plants as more in the middle of the discussion and more likely to side with the DRBC and the EPA.

"I give credit," Kricun said, "to the DRBC and their CEO at the time, Carol Collier, for putting together a stakeholder group to seek to identify the best approach to proceed, as opposed to just seeking to unilaterally impose numeric limits."

Kricun said he also credits the DRBC for its handling of the problem -- a best management approach to reduce PCBs to the maximum possible as opposed to numeric limits.

"Our (the wastewater treatment plants) reason for being is to protect the environment," said Kricun. "I consider myself an environmentalist."

That's not just words. Kricun is among the more progressive of wastewater engineers and if you check the Camden Utility's website, you'll find a section outlining its work building its Environmental Management System.

Camden Utility continues to be recognized as a Utility of the Future Today by a variety of industry groups, and Kricun is proud of the designation and explains that a new approach to wastewater-treatment operations incorporates a "triple bottom line: cost, environmental benefit and community benefit."

There are other differences between the PCB tussle and what's ahead for solving the dissolved-oxygen problem.

The PCBs weren't generated by the wastewater treatment plants, but passing through them.

And Kricun remembered that the initial goal set by the DRBC was "aspirational" and "there was no technology that could get us to that."

"Look, we're not trying to get away with anything," Kricun said. "The technology didn't exist and the DRBC understood that the technology didn't exist and they worked with us since we said we'd do everything we can to limit PCBs in the effluent.

"All we can do is our best."

That process seems to have worked, with DRBC's data showing a 76% reduction in PCB discharges from the top point sources since 2005

"I consider the DRBC and us to be collaborators," said Kricun, though he acknowledged that the dissolved-oxygen process is likely to lead to some regulations and that's where the relationship between the plants and Manko Gold might come more to the forefront if those regulations aren't, in the view of the plants, manageable or achievable.

Calls for more sturgeon studies

Kricun said that the reaction from the wastewater treatment plants to the DRBC's eventual solution to the dissolved-oxygen problem will likely depend on what the model indicates and how it is used to develop wasteload allocations -- that's what the model suggests each wastewater treatment plant's end-of-pipe goal is.

According to Namsoo Suk, the DRBC's director of science and water quality management, those allocations are part policy and part science. In other words, the model will provide the science but the DRBC will be involved in conversations with various stakeholders so as to ensure the burden of fixing the problem doesn't fall too hard on communities that do not have deep pockets.

As Kricun pointed out, the average median income in the city of Camden -- one of several municipalities whose waste is treated by his utility -- is $26,800.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, for Philadelphia and Wilmington the average median income there is about $40,000. Of course, all of the 12 top tier wastewater-treatment plants will have pockets of higher as well as lower incomes.

Cost can be a considerable obstacle, though the burden is not likely to rest entirely on the rates that residents are charged. Each state has a revolving fund with the federal government that offers low-income loans repaid over a long period that wastewater treatment plants can use.

The Camden Utility improved its plant in 2015 with a loan from New Jersey's Environmental Infrastructure Trust: 30 years at 1.5% interest. "Improvements happened without a rate increase for our citizens," said Kricun.

For the Philadelphia Water Department, capital funds from general obligation bonds will likely be used to build the planned ammonia-treatment facility. More information about the city's capital improvement plan for 2020-2025 is here.

Important to note that the city's capital budget is a six-year plan (2020-2025), which is in turn based on the city's long-range Philadelphia 2035. These dates offer some insight for the time frames involved. Infrastructure is a long-term investment.

Reviewing some of the wastewater treatments plants, there's some belt-and-suspenders approaches to the dissolved-oxygen issue. The Philadelphia Water Department is wasting no time tackling the problem, and at the same time disputing some of the rationale that is the basis for the DRBC's approach.

And when Ian Piro, formerly from DELCORA (Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority), was asked about the process, he said that there needed to be further "proof" -- like a new study -- that would explore the relationship between dissolved oxygen and juvenile sturgeon and only then could there be a demand for rectification of the problem.

Jason Cruz, a scientist in the Philadelphia Water Department, agreed in an e-mail:

"There is still a need for additional studies of the effects of low DO on Atlantic sturgeon early life stages. DRBC commissioned a study to address what they also acknowledge to be a gap, but unfortunately the study left a lot to be desired."

And Cruz acknowledged that there are some studies that "We have a moderate to high confidence in. These studies have shown low DO to be stressful and even lethal to juvenile sturgeon in the 3-3.5 mg/L range. But these studies need to be replicated with proper toxicological methods and test additional ages, temperatures, and salinity conditions.

"Sturgeon are potentially stressed by (several) factors in the Delaware River during dry, hot summers. It is difficult to determine which stressor or stressors are most important."

Three need to be examined, he said:

- The size of the population and sturgeons' life history, which cause the population to grow very slowly even under the best conditions

- Mortality due to commercial fishing interactions

- Mortality due to ship strikes.

Those are observations echoed by Dr. Dewayne Fox, fisheries professor at Delaware State University and an expert on the Delaware's sturgeon.

"I think there are other issues that don't get enough attention including the impact of dredging, habitat alternation, and mortalities caused by vessels (ship strikes)," wrote Fox in an e-mail.

It's important to remember that the Delaware River and Bay is home to many ports and the waterway is a busy one.

Philadelphia Water Department

According to DRBC research and analysis, the biggest contributor to the dissolved oxygen problem in the Delaware is the Philadelphia Water Department. We already know that the volume of ammonia discharged into the river is a big part of the problem and the river's biggest city would be expected to be producing the largest quantity of ammonia going into the river.

Adult Atlantic sturgeon (118 kg) collected off the Delaware Coast by prominent sturgeon researchers Drs. Dewayne Fox and Matt Breece, with an anchor gill net in April 2012. A fin clip was taken for DNA analysis and the specimen was implanted with an acoustic transmitter to monitor its coastal movements. This activity was conducted pursuant to NMFS permit 16507 (image courtesy of Delaware State University)

Philadelphia Water Department is a complicated entity and if you're interested you can read all about it here.

Even better, if you're interested, you can visit the Fairmount Water Works and see what the water system is all about, past, present and future, here

But taking a quick review, the city's wastewater treatment system has four main components, three water treatment facilities and one Biosolids Recycling Center. More on that here.

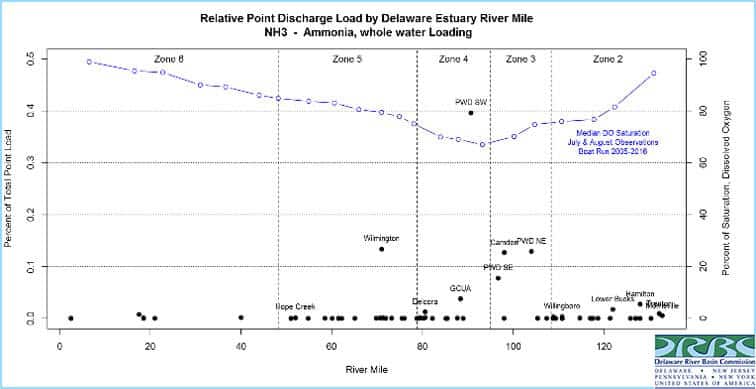

As you can see from the panel, two of the three wastewater treatment plants have similar NH3 (ammonia) levels. One, the Southwest Water Pollution Control Plant, has twice those amounts and that's mostly because the solids remaining from the waste-treatment processes from all three plants gets re-processed at the Biosolids Recycling Center and the remaining liquid goes into the Southwest Water Pollution Control Plant stream and then into the river. There is a multiplication of ammonia residue as it gets reprocessed at the Southwest Water Pollution Control Plant.

The Philadelphia Water Department has been treating and processing biosolids -- the material that's been strained out of the treated wastewater -- for decades.

More here.

In other plants, like DELCORA just downriver, those biosolids are burned, and upriver in Hancock, N.Y., they are dried and carted off to a landfill, and that was what used to happen in Philadelphia. Now, PWD's residue is heated and dried into pathogen-free pellets used as fertilizer and fuel.

In Camden, the dried sludge is either used as a fuel, replacing coal, in a cement kiln or reused as landfill cover.

It's sort of ironic to note that as the PWD was improving its environmental footprint in how it handled that residue, it ended up creating a different headache: the increase in ammonia discharged into the river. The technology and knowledge of how to handle our various wastes is always advancing and that's a good thing -- but the accompanying improvements can be costly.

The PWD is hardly standing still and waiting for a DRBC resolution. Back in 2015, according to Cruz, "Hazen and Sawyer (now just Hazen) delivered a report that recommended a sidestream (separate waste stream flow from the main influent to the plant) de-ammonification (ANAMMOX) process for the BRC centrate."

Translation? That report suggested taking the effluent out of the main waste stream and treating with yet another nitrifying bug, ANAMMOX, short for anaerobic ammonium oxidation. This is an interesting bacteria, recently recognized for its role in wastewater treatment, more widely used in Europe. It does its nitrifying magic where there is no oxygen. Interesting, again, since much of the more routine process of nitrifying relies on oxygen.

Just down the road at the DELCORA plant, it's the ample amount of oxygen available for the wastewater treatment system that allows it to have a relatively low load of ammonia going into the Delaware -- one of the lowest of the Tier 1 plants. As PWD's Cruz explains:

"With a good population of nitrifying bacteria, adequate time, aeration and suitable pH conditions, nitrification can take place in wastewater treatment plants. DELCORA (Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority) is an example of a wastewater treatment plant in the Delaware estuary that almost fully nitrifies its effluent."

Complicated systems need complicated solutions

Yes, it's complicated. Your eyes might be glazing over, but hold on. One of the reasons that the model that the DRBC is working on plays such an important role is that complicated wastewater-treatment systems empty into a complicated river system.

The idea behind the modeling is to "prove" which of these plants need to do what to solve the problem. (All the plants and DRBC already know which are the biggest contributors, as the above list shows.)

Van Rossum believes that if the DRBC improves that dissolved oxygen standard, that "Industry and experts will rise to the occasion. They will find a solution that makes financial sense.

"We've got a lot of smart people involved in this situation, they are just not being asked for their best."

That's a line of thinking that reminds Kricun of the initial missteps of the PCB process. Avoiding those missteps is important, he said.

"I do not have a knee-jerk reaction to say no. In fact I would say yes until I have to say no," said Kricun.

"When the model is done and the science is good and the technology is available and we see that this is what we ought to do and we can fund it over time, before I say no, I'd want to say yes until I can't say yes.

"I'm glad to be involved in any process that reaps environmental benefit."

***********

Thanks to many people for their patience with my endless questions! Don't blame them if I didn't get it right! (But let me know!)

Namsoo Suk and John Yagecic from the Delaware River Basin Commission; Maya van Rossum and Erik Silldorff from the Delaware Riverkeeper Network; Angela Padeletti from the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary; John Jackson from Stroud Water Research Center; David Velinsky from Drexel University; David Wolansky from Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control; Dr. Dewayne Fox from Delaware State University; Andy Kricun, chief engineer for the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority; Ian Piro, formerly with DELCORA and now with Isles, Inc; Jason Cruz, Philadelphia Water Department

Special thanks to my Environmental Leadership Program colleague, Christina Catanese who connected me with Celia Helfrich. Celia patiently created and re-created the delightful graphic illustrations as my understanding of the problem deepened. Thank you !

There's a part 3 in a couple of weeks: understanding the dissolved-oxygen problem by building a computer model of the Delaware Bay. It's ALL about the science.