Turning Passion into Stewardship

Women and Their Woods

"Close your eyes.

"What do you see?

"What do you hear?

"Do you hear chirping?

"Water?

"What do you feel?

"If you're sitting, are your pants getting damp?

"Is there a mosquito?

"Do you smell white pine?

"If you're sitting on a fallen log, do you smell decay?

"Are you comfortable?

"Are you calm?

"Are you fearful?

"Is there anyone with you?

"Now, open your eyes."

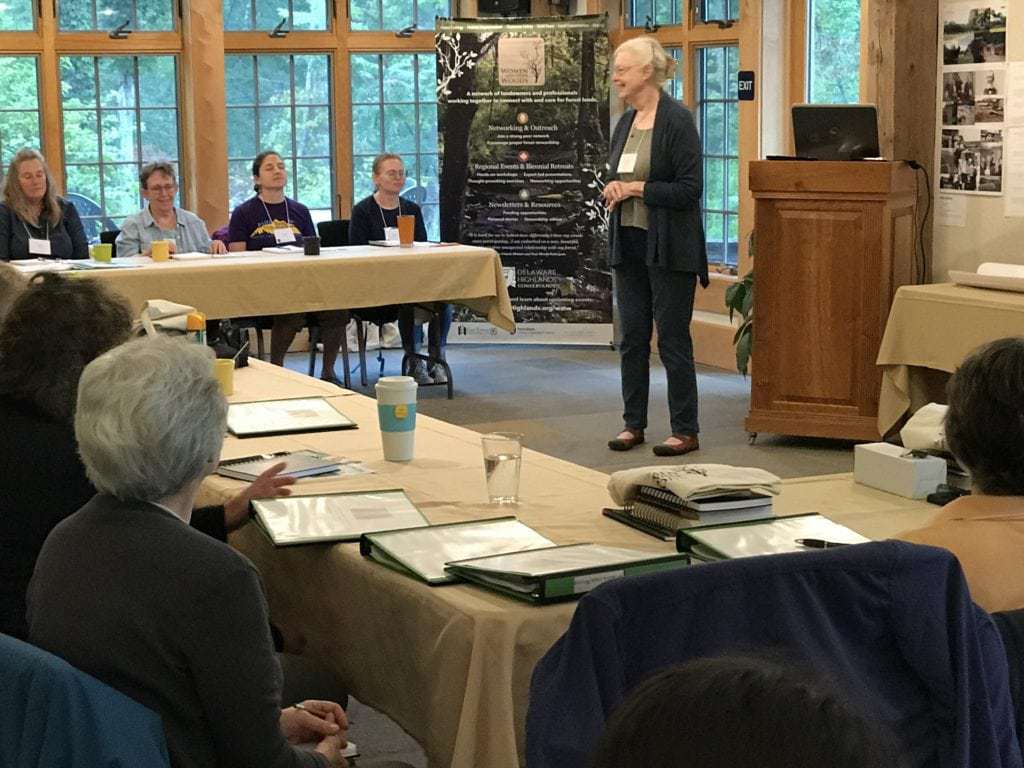

So began the work Friday morning at the Women and Their Woods weekend retreat, with the quiet calm of Nancy Baker's voice, taking the 26 women on this retreat for an interior journey.

That journey would be the start of capturing the place that they loved -- their woods.

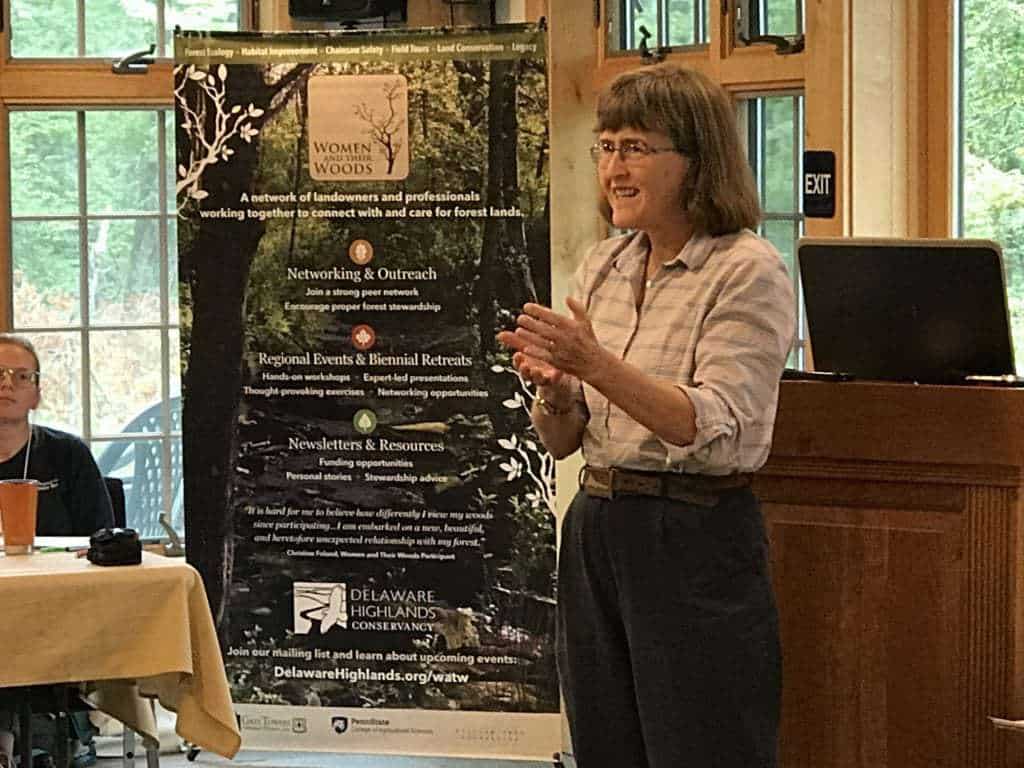

This women-only retreat is the fifth hosted by the Delaware Highlands Conservancy and is the joint brainchild of Amanda Subjin from the Delaware Highlands Conservancy, and Allyson Muth from the Center for Private Forests at Penn State University.

Subjin explained that she had been a student of Muth's at Penn State and she was inspired by workshops that Pennsylvania Forest Stewardship Program run out of Penn State's Center for Private Forests.

https://ecosystems.psu.edu/research/centers/private-forests/outreach/pennsylvania-forest-stewards

Subjin and DHC began women-only workshops in 2008 at Grey Towers (Gifford Pinchot's former house in Milford, Pa.)

"The women demanded more," Subjin said with a smile, "They were information hungry."

So they created more workshops, three to five a year.

Still not enough. Bigger smile.

So Subjin teamed up with Muth to create weekend retreats in 2011.

The funders for this retreat are the reason that it's offered for $300 for the four days. Funders include the U.S. Forest Service at Grey Towers National Historic Site; Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences; Pocono Forests and Waters (through DCNR and Pocono Environmental Council); the William Penn Foundation; and the Wayne County Community Foundation.

The focus is not just the Delaware River watershed. Attendees are welcome from all over -- these women live in Massachusetts, North Carolina and West Virginia as well as Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey. Their woods are likewise far flung. Some of the women live in or near the woods they love. Some live there part of the year. Some just visit.

Some aim to keep the woods as natural as possible. Some aim to farm the trees. Some don't own the woods they love but remember woods from their childhood and have an aim to eventually own their own woods. Some own more than 700 acres. Some manage 60,000 acres.

There have been five of these retreats so far, and both Subjin and Muth credit the women who have come to the retreats with helping to create the cooperative atmosphere as well as the various areas of study and conversation. The retreats reinvent themselves with some women coming back more than once.

And though the sponsoring organization is the Delaware Highlands Conservancy, Subjin stressed that making all the attendees into carbon copies of how to become stewards is not the mission of the retreat.

The mission of the Delaware Highlands Conservancy is certainly land protection, according to its president, Karen Lutz, who was one of several audience members happy to listen and learn.

"Delaware Highland Conservancy's mission is to conserve and protect land to provide clean water and to protect wildlife habitat from development," she explained.

The majority of the conservation DHC works on happens through easements, which means that the land can still be used, maybe as a farm or open space or for timber, but that it's not going to be developed.

This conservation possibility will be discussed with an evening panel, but so will the farming of timber as a business. Another huge concern for many women is legacy: What happens to these woods when they pass on? That, too, is discussed.

OK, back up: Women only? Why is that? Don't men have an interest in and passion for woods?

The vibe at women-only events is different say the organizers. Women feel more comfortable sharing with other women, and often start from a place where they don't have the self-confidence that they have earned with the work they already do for their woods.

Sarah Wurzbacher, a forestry extension educator with PennState Extension, explained further. As a natural resources professional, she's become quite used to being the only woman in a professional gathering, but she understands that the overwhelming number of men in the field can be off-putting for women, especially if they are not, themselves, professionals.

Another presenter, Susan Stout, suggested, "We all know men who love the woods as much as we do, but maybe they're less free to describe it the way we have. Your gift to them is to share this experience with them."

Let's get back to the fun stuff, the retreat!

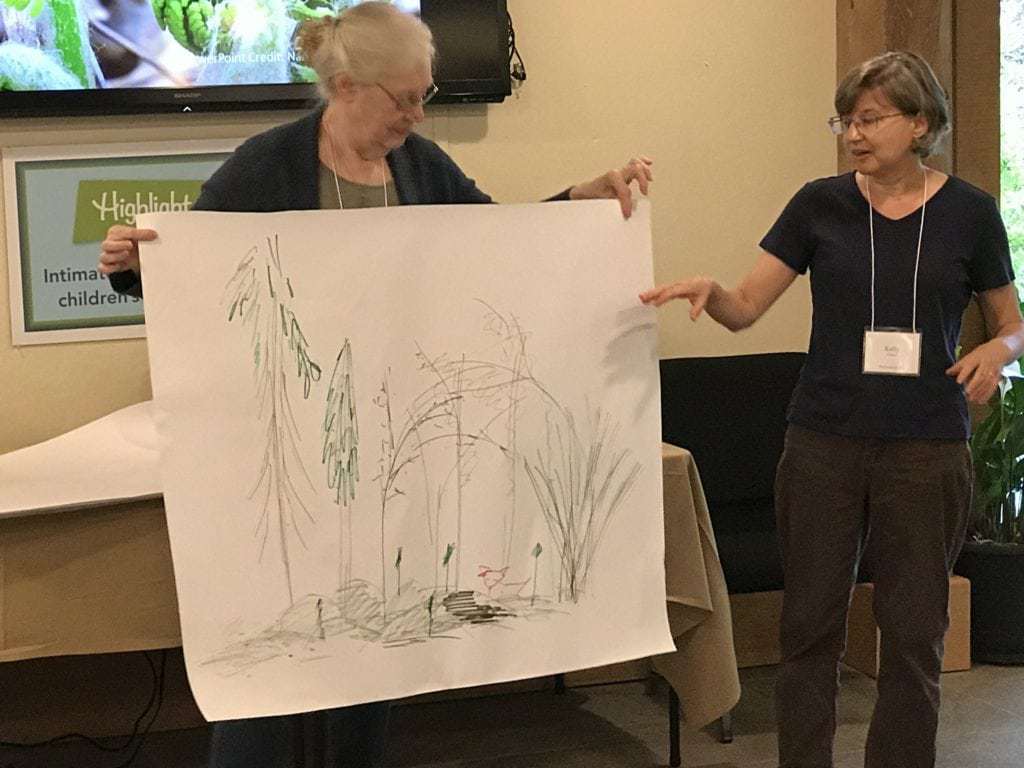

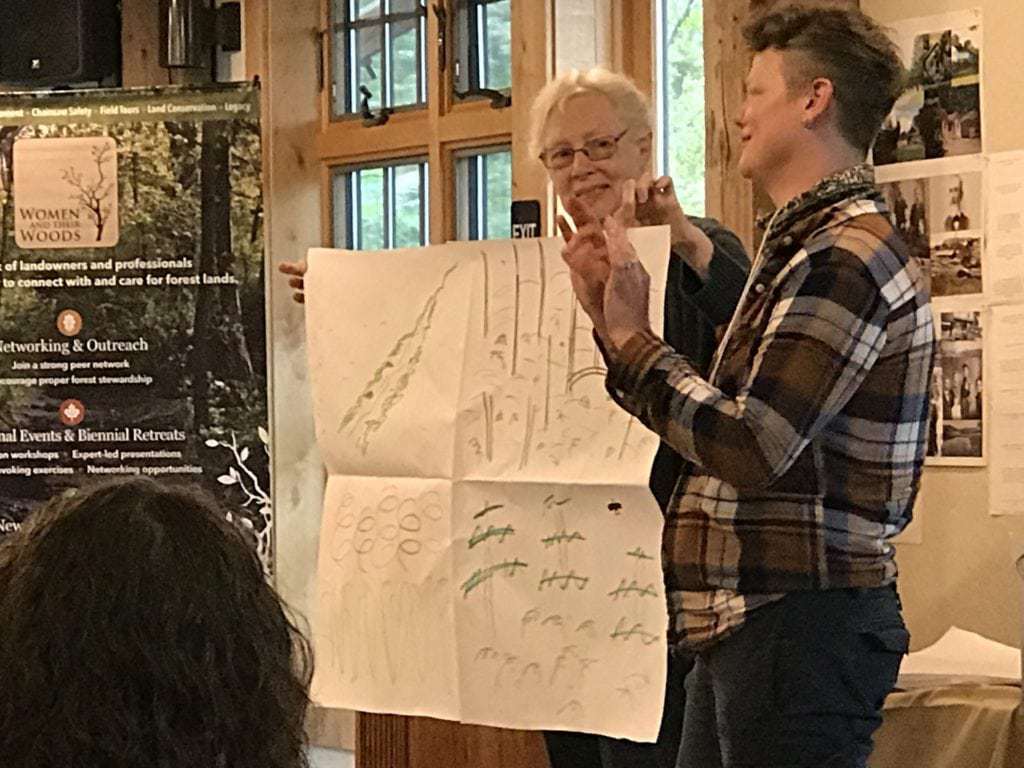

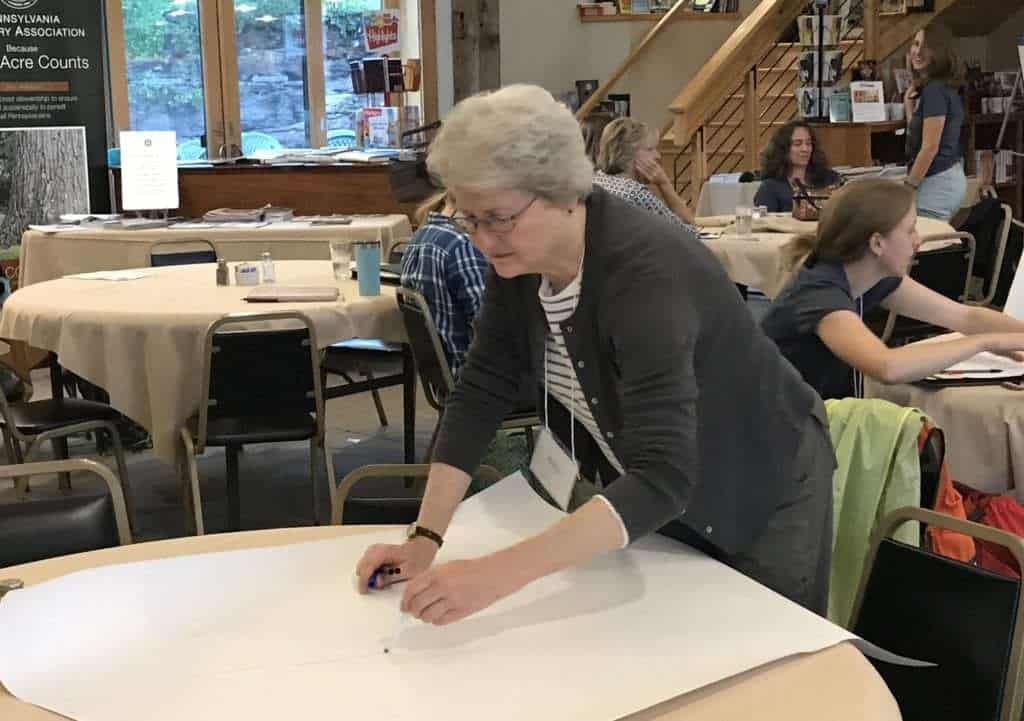

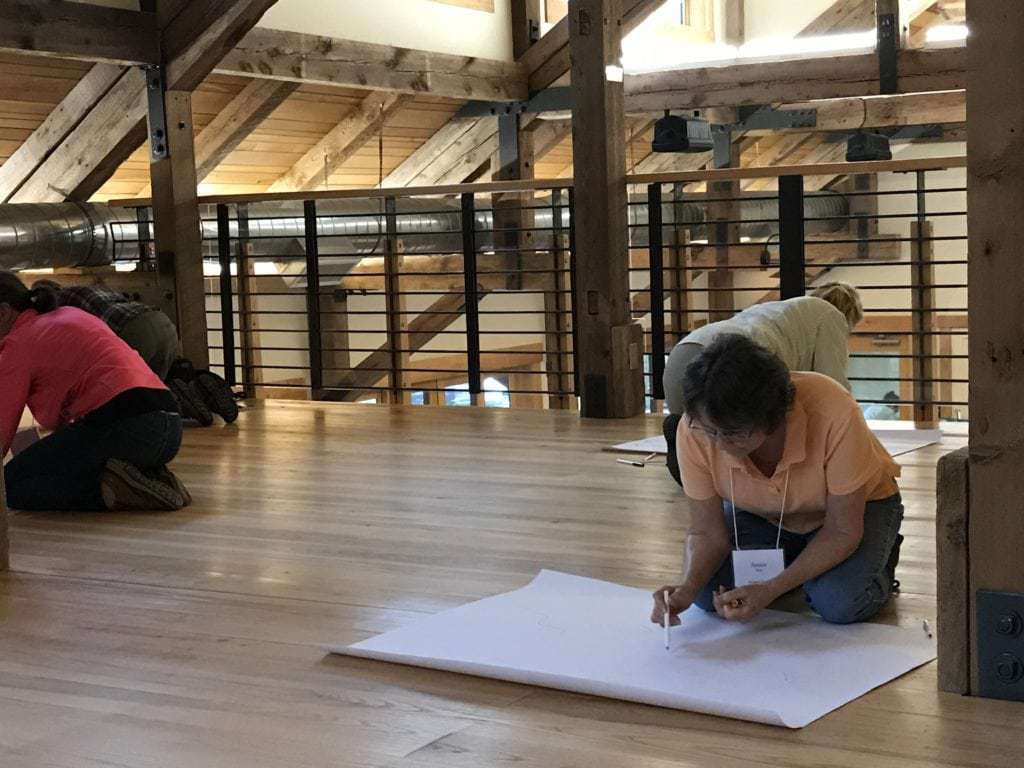

The first task for the attendees was to do a similar "map" inside their own heads of their woods -- to create what Baker, who is herself a landowner in Pennsylvania and a Pennsylvania Forest Steward, called a cognitive map of their woods. These aren't Google maps, but a mapping of what a special place means to you, which may not be recognizable to anyone else. That's not the point.

Nancy Baker holds the cognitive map created by Kelly Austin from Saylorsburg, Pa. If you look closely, you can see a little red fox hanging out at the bottom. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

Nancy Baker holds the cognitive map drawn by woodland owner Kerry Engelhardt, from Hawley, Pa. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

As if to prove that, three sisters -- Vicky, Martha and Jennie Berg, who jointly care for woods in the Allegheny watershed -- each drew her own cognitive map of their woods. They didn't look alike at all.

As Baker explained, "These aren't rational, but intuitive."

The women took 10 minutes to create some visualization of that special place to share it with each other -- could be as a drawing or a poem.

Or a bag.

Denise (Dee) Weber (from Greentown, Pa.) wanted to create the smell of her woodland, so she fished a lightly used brown bag out of the trash and went outside to gather fallen artifacts of woods for people to smell the outdoorsy smell that typifies her woods, and which resonates with her.

Unfortunately, the bag had recently contained coffee, which she didn't discover until too late! That smell overwhelmed the woodsy smell.

Everyone laughed at the mishap, but she accidentally made a point that Stout later emphasized: Wrong decisions can be a part of the best intentioned stewardship.

Stout is a research forester emeritus from the U.S. Forest Service and she explained how decisions made with the best of intentions can backfire, sometimes we only recognize our errors with the passage of time.

She reminded the audience that once we thought that fires were bad for forests. Now, we know better.

"But we accidentally created forests that were disasters in the making," she said.

This question of risk, of choosing the right course of action vexed some:

"Will the woods want to take care of itself?" asked Diane Owen Garber, (from Wrightsville, Pa.) referencing a sense shared by several women that not doing anything to their woods would be the most natural way to steward.

Gently, Stout pointed out that there really isn't any way for a modern forest to heal itself. Trees are plagued by acid rain and other pollution and attacked by new bugs with the advent of climate change. Those changes will only become more pronounced as the climate continues to evolve.

"Part of stewardship is tolerance," Stout said, "and part may be destructive. How will you deal with invasive species, or tackle overgrowth that threatens the woods?

"We're all going to be wrong in big or little ways. I say this not to frighten you, but to free you. You have to find your own balance."

She said that as she listened to the women she could hear how much they "already get it." They love their woods.

Now, she suggested that their jobs are like a marriage. First there's the love and then, for a marriage to be successful, there needs to be the work you put into it.

The next question was about priorities, with so much to do, what should we do first?

Stout replied that it was an existential question: "It doesn't much matter what you choose to do first. There's always too much to do. But you find what gives you joy -- joy is a big part of stewardship."

And lastly, "You need a little knowledge with your love."

So Jane Swift was introduced. She's the environmental education specialist with Pennsylvania's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources at Worlds End State Park. Her task was to help the attendees figure out how to identify trees: by bark and leaf; by stem and shape; by fruits, cones and telltale odors.

Then everyone trooped outside -- rain notwithstanding -- to see how they much they learned in a very short time. Sure enough they named the massive sugar maple as well as a young red maple.

Then another old giant, a red oak, then a gnarled black walnut and finally an ash tree.

The site of the retreat was the Highlights Foundation Workshop Facility in Boyds Mills, Pa., way, way off the beaten track.

The outside interval was interspersed with stories about their woods and the plight of trees in the time of climate change and especially the plight of the Pennsylvania state tree: the eastern Hemlock and what to do about the pernicious woolly adelgid.

"It's such a special tree," she said. "We really need it for the shade it offers for little streams and the hemlocks help keep the waters clean."

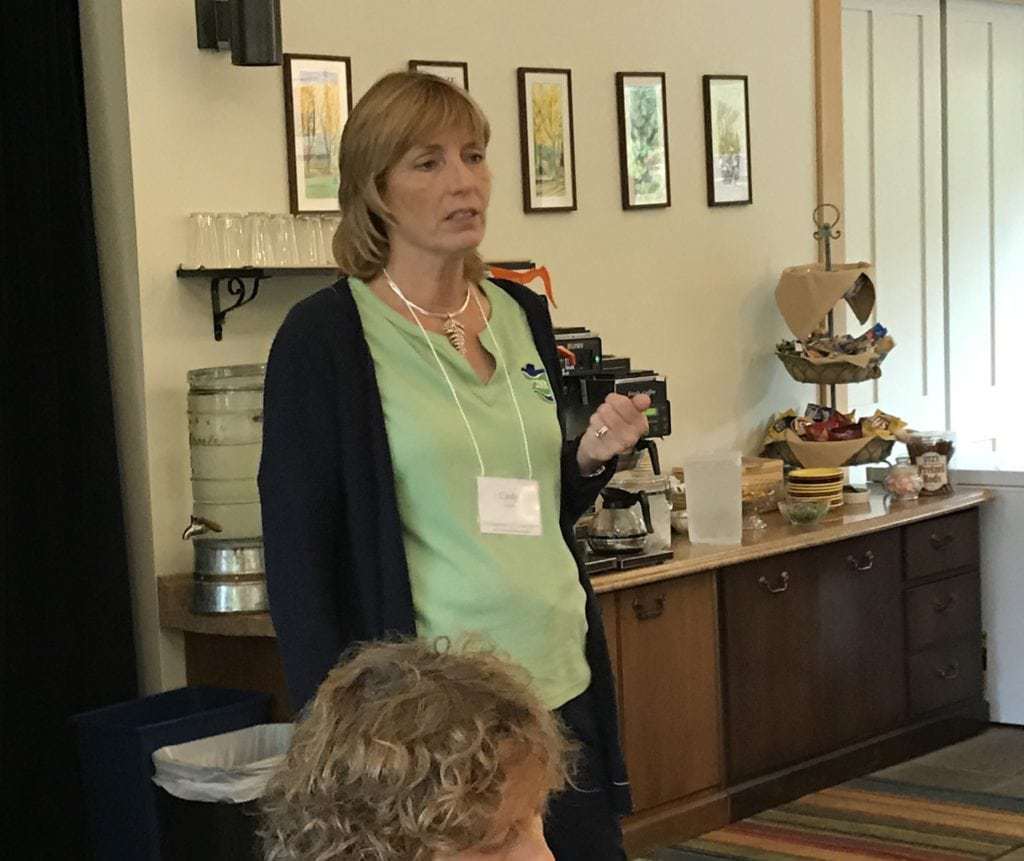

It was time to get back inside and greet a special guest: Pennsylvania's DCNR Secretary Cindy Adams Dunn, who introduced Ellen Shultzabarger -- the new state forester and director of the Bureau of Forestry, and Tim Dugan, district forester, PA DCNR Bureau of Forestry.

All offered encouraging words to the women in attendance and welcomed partnerships with private landowners.

"We (DCNR) manage about 2.2 million acres but the vast majority of forests are in private hands,' said Dunn. She relayed the commitment of Gov. Tom Wolf to conserving Pennsylvania's forests and said that he is especially interested in what the forest lands can do to help prevent or lessen the damages caused by flash flooding and in forests' role in providing clean water.

Wolf, Dunn said, is also interested in how this sector can boost the state's economy by offering jobs and nurturing small businesses that help look after the forests as well as business that farm timber, and use hardwoods to create marketable products.

But the real stars of the retreat are the women themselves. Let's listen in as they described the cognitive maps they made.

First though, there were tears at the prospect of sharing the map with the rest of the class but the exhilaration found lots of different expressions.

"I still can't believe I own it!"

"See -- that heron is trying to kill the frogs, if the water snake doesn't get them first."

"I have a hill."

"I have a geriatric skunk."

"When the ferns are out I know it's spring."

"I'm learning, I'm learning. I'm learning!"

"Stone walls are home."

"My address is a Post Office box."

Lastly, enjoy the story of three sisters who all attended the retreat who co-own property in Clarion County, Pa.:

Vicky (from Dedham, Mass), Martha (from Pittsburgh, Pa.) and Jennie Berg (from Shippenville, Pa.)

Vicky Berg from Dedham, Ma. begins to draw a cognitive "map" of the woodlands she shares with her sisters. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

Martha Berg from Pittsburgh, Pa., one of three sisters attending the retreat, begins work on her intuitive map. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

It was their grandfather -- family name McKnight -- who originally bought the land in the 1920s: 800 acres in Clarion County, Pa.

Vicky: It was bare and rocky.

DC: Why?

Martha: Clear cutting

Vicky: He liked the woods, but the land wasn't valued back then.

Martha: It was called wasteland. He replanted a few areas, there was a lot of natural regeneration, and now the land is almost completely reforested.

Jennie: He lived near Pittsburgh.

Martha: It passed to our mother. She was the custodian, There was an occasional timber sale.

But it was really our brother...

Vicky: .. Parker Berg...

Martha: ...who really took the land seriously. He built the first cabin in the woods when he was 16.

Jennie: Our brother was a true forest manager. He held an annual meeting for all of us.

Martha: We tried to get more involved but we had children and families.

DC: Is he still involved?

Martha: He passed 15 years ago.

Jennie: We weren't hands-on until Parker died. It just dropped in our laps.

Vicky: It was a steep learning curve.

Smiles all around

VIcky: Slowly, ploddingly we began to learn.

Jennie: Eventually we found a map of the woods and we could see what areas had been cut and when, and what our brother's plan was.

Martha: We always work with a forester.

Where did you find a forester?

Jennie: You can start with Pennsylvania's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Or ask other forest landowners.

Vicky: We co-own the property, with the children, who are the future.

Are you interested in this program? Contact Delaware Highlands Conservancy at www.delawarehighlands.org

Dear Meg,

I enjoyed reliving the retreat through your article. Though my name is Rachel Victoria Berg, I am called Vicky. Could you please change the Rachel?

Thank you, Vicky