Hearings on fracking ban draw mostly support

Audiences like this gathered to express strong opinions about the proposed -- now passed -- fracking ban. This was at the afternoon hearing at Waymart, Pa. at Ladore Retreat and Conference Center. The upcoming hearings will be virtual. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

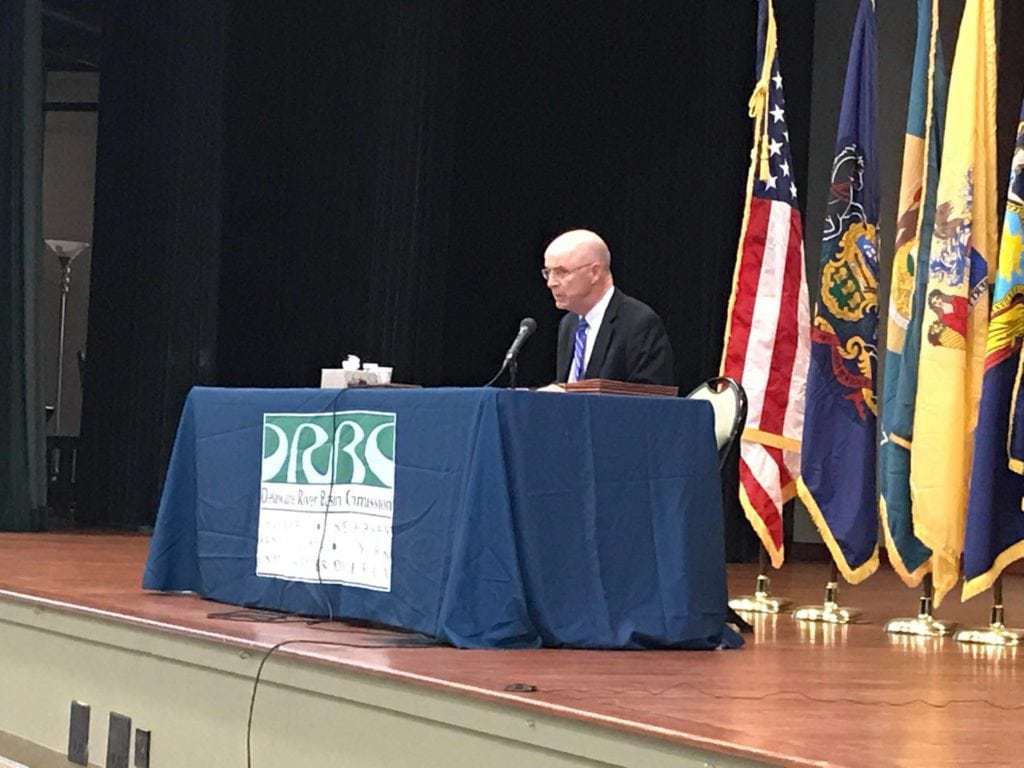

William Ford , a retired Pennsylvania state trial judge, is the hearing officer for the DRBC's public hearings on its proposed fracking ban — at Ladore Retreat and Conference Center.

Shannon Pendelton, an architect from Solebury, which is on the Delaware River, spoke about the poor track record of keeping fracking contaminants out of the drinking water. — at DoubleTree by Hilton Philadelphia Airport.

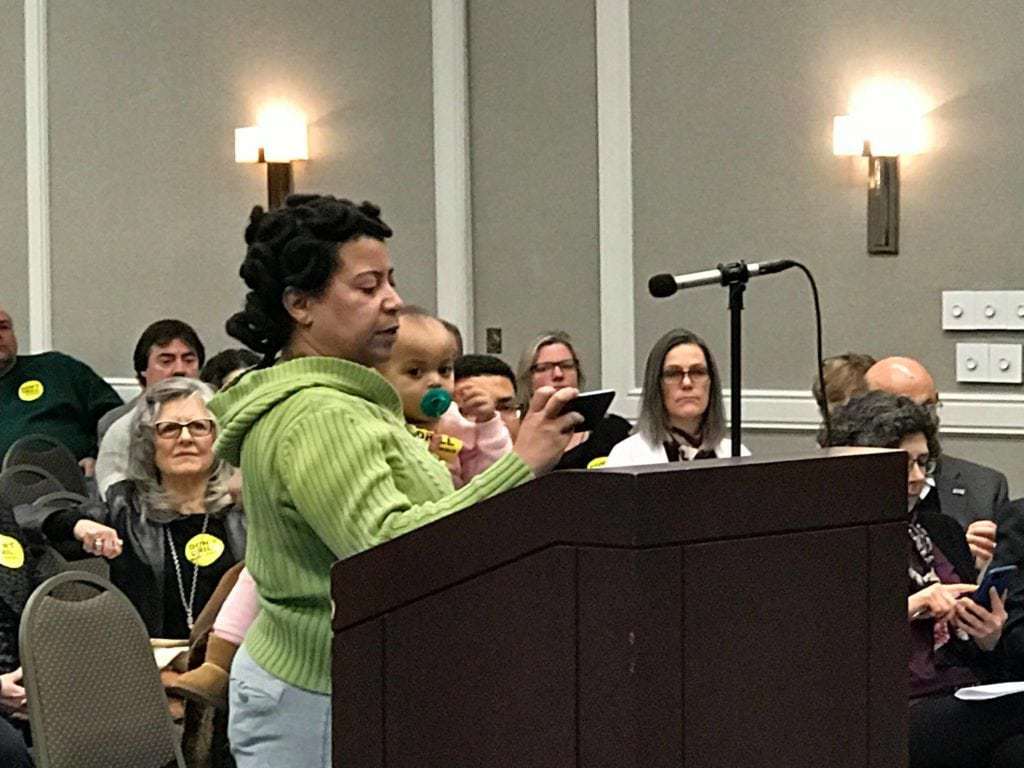

Alicia Dorsey, of Strawberry Mansion in northwest Philadelphia, holds her granddaughter, Caleigh Dorsey as she speaks at the DRBC public hearing on the proposed fracking ban. Both wore the ubiquitous yellow sticker 'Don't drill the Delaware.'

Many of the organizations that have been fighting for a ban are pictured at a press conference before the Jan. 23rd hearing in Waymart, Pa. hearing: Front and center, Tracy Carlucci, from the Delaware Riverkeeper Network; slightly behind her, in a red coat, is Barbara Arrindell from Damascus Citizens for Sustainability; to her right in a green coat is Jeff Tittel, director of the NJ Sierra Club; on Carlucci's left, is Wes Gillingham, associate director of Catskill Mountainkeeper and behind him in a pink shirt is Junior Romero, NJ organizer for Food and Water Watch. Not pictured is Robert Friedman from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

A massive, sullen mountain lies between Carbondale and Waymart, Pa. -- the site of the first two public hearings on Jan. 23 on the proposed ban on fracking in the Delaware River watershed. The top of the mountain marks the border between the Delaware River Basin and the Susquehanna River Basin.

No ban exists on fracking in the Susquehanna River Basin. Over there, you can lease your land to a gas drilling company and maybe make some money -- that "windfall" will depend on gas being being produced. In many cases, gas companies drive hard bargains, and money doesn't necessarily flow any easier than the gas does.

If, however, you live on "this" (the Waymart) side of the mountain -- maybe two miles from the site of this meeting -- this ban means no fracking money for you. Again, there's nothing guaranteed, at the edges of the Marcellus shale formation, gas is less plentiful.

But you can see why some people at this hearing were up in arms about what they called the "illegal taking" of their land rights. Yes, most of the people who spoke against the proposed ban are land owners, and large tracts of land always seem to city folks to mean "rich." But in these parts, most of those tracts of land are farms -- not a lot of riches there. Also, the rich hire lawyers to make their point and don't necessarily frequent public hearings.

On the other hand, the majority of the speakers were up in arms about a different sort of "taking."

The risk of fracking "taking" clean air and water from the rest of the residents of the watershed. Many referred to the new more broad interpretation of Article 1 Section 27 of the Pennsylvania Constitution -- referred to as the Environmental Right Amendment -- which was passed by referendum in 1971:

The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.

An impasse, certainly, but what was most striking about the two gatherings in Waymart, despite the clear passion on both sides, was its civility. That was largely due to the structure of the hearing. The Delaware River Basin Commission, the organizer of the hearings, set the stage for civility. It hired a retired judge -- William Ford -- to be the "face" of the hearing. He was gentle and respectful but announced his intention to stick to those rules, which he explained beforehand. In true DRBC fashion, the ground rules were a bit complicated, but it said it wanted to be fair, and largely, the attendees seemed to feel the hearings were.

The people against the ban railed against the DRBC for proposing it.

Showing knowledge of the structure of the DRBC, they railed against the commissioners, who are the state governors from New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware.

They railed specifically against Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf's support of the fracking ban in the Delaware watershed and compared that to his enthusiastic support of fracking "over the mountain."

They complained that he was sacrificing their rights to the votes he needs in Philadelphia. But 'twas ever thus: politics creates policy.

There were about 300 in the two meetings combined in Waymart, about 200 in the afternoon and maybe 100 in the evening. The great majority spoke in favor of the ban.

Then there were two public hearings on Jan. 25 in Philadelphia with less attendees at both the afternoon hearing (about 125) and evening (about 75).

Here, the geographic backdrop for the hearing was the busy industrial landscape of Southwest Philly: An airport, oil storage tanks and factories that combined to create what looked from Island Avenue to be a celebration of fossil fuels.

Most of the people who spoke against the ban both in Waymart and at the third and fourth public hearings, focused on the ban and didn't say much about the two other proposed regulations. One would allow water to be taken from the Delaware watershed to be used in the very thirsty fracking process. The other would allow the water from the fracking process to be imported into the basin. People who supported the ban and thanked the DRBC for proposing it, on the other hand, were up in arms about the two water regulations.

Speakers pointed out that only very recently the watershed experienced a drought, and water taken from the watershed for fracking outside of the watershed would not be returning to the water cycle.

In addition, many speakers pointed out that if fracking is bad and could cause harm to the watershed's waters, why would the DRBC allow fracked water into the watershed? The DRBC's own notes on its website discuss at length the many known and unknown chemicals that are routinely found in fracking wastewater that pose a risk.

Queried as to why these proposed regulations ban fracking but not the water from fracking, Clarke Rupert, the communication manager of the DRBC pointed out that the "allowance" of waters in or out is subject to rules which are proposed to be tightened as part of this rule-making process. At the moment, the importing water limit of more than 50,000 gallons daily is subject to DRBC approval; the limit for exportation is 100,000 gallons daily. The new rules for high volume hydraulic fracturing demands any import or export of water gain the DRBC's approval, and the revised approval process is daunting.

Pressed, Rupert explained that these proposed rules are what the executive director developed at the commissioners' request. That request was for new rules about the import and export of water involved in the fracking process. But he pointed out that the commissioners have the final say so. If they wish, the regulations could be changed to forbid either the import or the export of water as well as forbidding fracking.

When you read "commissioners," remember that the commissioners are the governors of the four states in the watershed, and if politics creates policy, look closely.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo banned fracking in New York state (although not the pipelines that carry fracked gas).

New Jersey's governorship has flipped from fossil-fuel-friendly Republican Chris Christie to Democrat Phil Murphy, who supports a clean energy future for New Jersey.

Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf -- as previously noted -- has publicly said that he supported a ban in fracking in the watershed.

Another Democrat, John Carney, governor of Delaware, took office in 2017. As U.S. Representative, Carney was a key supporter of the Delaware River Basin Conservation Act, signed by then-president, Barrack Obama, but still unfunded.

The only non-Democrat is the non-partisan U.S.Army Corps of Engineers. It votes the will of the occupant of the White House.

Not hard to read these tea leaves and figure out that the ban will be enacted. Harder to guess if the commissioners might change their minds about the water regulations.

On to the next public hearing in Schnecksville, Pa. on February 22, from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m.

The DRBC suggests that you register on line to insure there isn't a overflow crowd, check out the info here: http://www.state.nj.us/…/20180108_newsrel_hydraulic-fractur…

On March 6, there will be a moderated telephone public hearing and written comments will be accepted until March 30. The process for submitting comments is outlined at the above page in the DRBC's website.