Next steps for New Jersey in its battle against climate change

Slides presented at 'Climate Change Policy in New Jersey,' a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

Slides presented at 'Climate Change Policy in New Jersey,' a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

Slides presented at 'Climate Change Policy in New Jersey,' a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

Slides presented at 'Climate Change Policy in New Jersey,' a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

Slides presented at 'Climate Change Policy in New Jersey,' a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

The past eight years have been trying for many in the room for "Climate Change Policy in New Jersey," a conference held on Sept. 27 at Duke Farms in Hillsborough, N.J.

Some of the 300-plus attendees are employees of the state in various departments who have been kept on a very tight rein while Republican Chris Christie was in charge.

Others are Rutgers faculty and leaders in the non-profit environmental field who likely have been frustrated by the state's seeming indifference to this problem, which isn't just on the state's doorstep, but washing over it. Still others are representatives of business and industry who have not waited for government to get on the bus -- their obligations are to shareholders and customers and they can't wait for the political dust storm to clear.

"We've been eight years out in the wilderness," said Kathleen Ellis, executive vice president of New Jersey Resources, a New Jersey natural gas supply company. "This conference will get you ready for what's to come."

So there was anticipation that the leash would be loosened when and if a Democratic governor wins the upcoming election.

But the keynote speaker had a different message: "It's time to break through this climate change divide. It cannot be a blue state/red state issue," said Mindy Lubber, the president and CEO of Ceres, a not-for profit organization that works to advance sustainability leadership among investors, companies and capital market influencers --not the folks typically seen as tree-huggers.

Lubber presented a vision of solving environmental problems that embraced both the concerns of environmentalists and the needs of business. A view that takes the conversation beyond politics. The wave of the future in business, Lubber maintains, is sustainability. Now.

She noted that even though red and blue states are in a battle over inviting Amazon to their state, she is willing to wager that the company is only going to end up in a state that has a good sustainability track record.

So here's an thought: Clearly environmentalists -- scientists and advocates -- are already concerned and committed. It seems that many of the high-end, forward-thinking companies (she mentioned Mars, Tesla, Bank of America among others) are concerned and committed. The odd man out of this problem-solving solution is political leadership. Many levels of politicians use the issue of climate change to divide rather than unite the energy of the voters. More on that in a minute.

There's evidence that something along Lubber's suggested line is afoot.

This conference was presented by the New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance -- njadapt.rutgers.edu -- a Rutgers-based group formed in 2011. Right now, James J. Florio, a former Democratic New Jersey governor, and Thomas H. Kean, a former Republican New Jersey governor are honorary co-chairmen of its advisory committee.

How's that for a foretaste of what Lubber is describing?

Once our politicians are no longer politicking, they can speak about the things that concern them without regard to whatever the platform is of their party. Also on that committee is a former New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection commissioner, Michael Catania, now the executive director of Duke Farms. Another member is former NJDEP Commissioner Mark Mauriello and a former NJDEP chief of staff, Gary Sondermeyer.

Many members of that committee signed a letter that was distributed at the conference, so a next step has already been taken.

Entitled "Advancing Sound, Science-informed Climate Change Policy in New Jersey." It begins:

"Changing climate conditions have and will continue to have devastating impacts on New jersey's economy, the health of our residents, the state's natural resources and the extensive infrastructure that delivers transportation services, energy and clean water to millions of New Jerseyans. "

Find it here: http://climatechange.rutgers.edu and look for "New Report on Climate Mitigation for New Jersey Available"

The day was spent talking about next steps, from how to make sure senior citizens have the protection they need when storms hit, to the problem that cap-and-trade policies can create for low-income communities, already among the hardest hit from local air and water pollution.

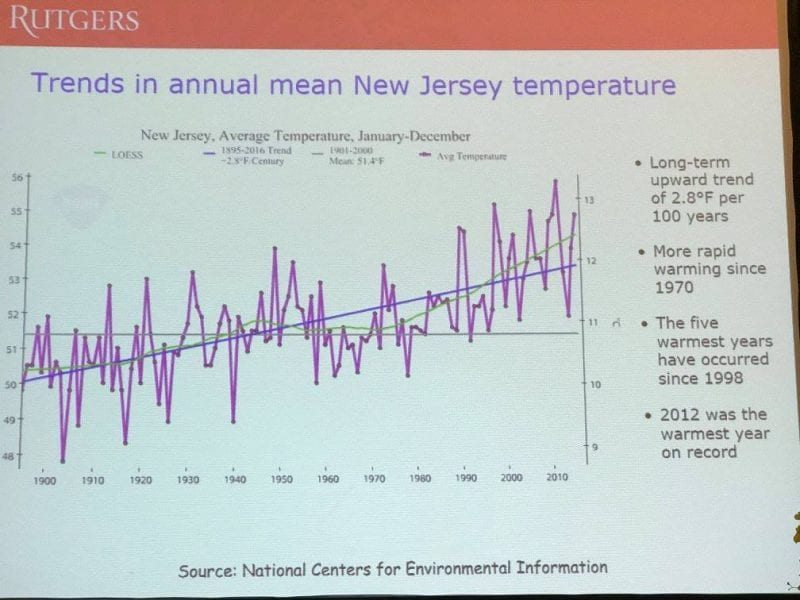

First up with an unsettling view of New Jersey's climate was Anthony Broccoli, co-director of the Rutgers Climate Institute. He had, being a scientist, lots of facts and figures but he didn't need to persuade this audience. They were here to move ahead.

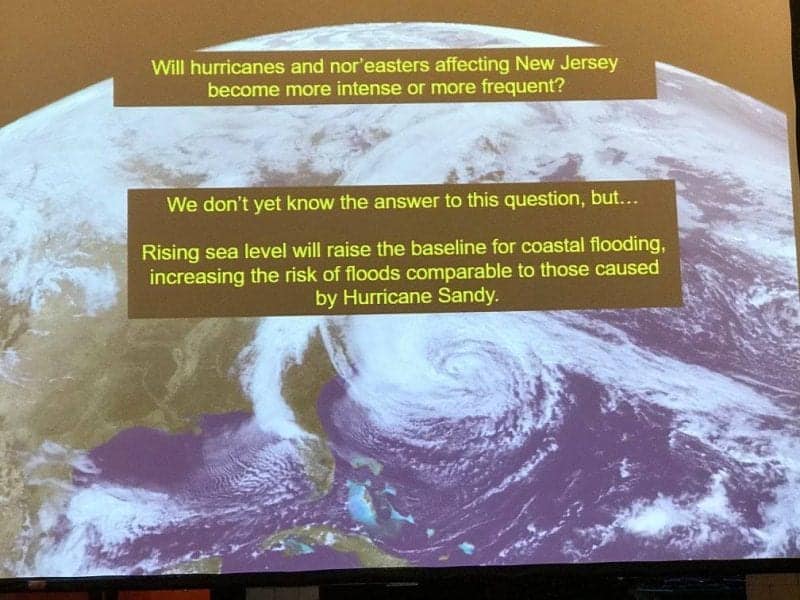

"Sea-level rise on average globally is 2 mm annually," he said. Because New Jersey is sinking, the figure here is 4 mm annually. "New Jersey is a hot spot for sea-level rise." The weather is likely to get hotter and wetter. We're not likely to see more storms, he said, but the storms we have will be stronger.

"It's not a nice story," Broccoli said, "But unlike other problems we have, this is one we can do something about."

Doing something about it requires some appreciation of the risks. At this gathering the risks were understood. Unfortunately, many people outside this knowledgeable community have little expectation that climate change will influence them personally.

Marjorie Kaplan, the associate director of Rutgers Climate Institute presented slides that showed results of a poll taken in 2016:

● 58 percent of the people polled were "worried about global warming"

which leaves 42 percent "not worried."

● 70 percent (the highest percentage) believed global warming will harm future generations

● 69 percent believed global warning will harm plants and animals.

(That might be the result of seeing polar bears trapped on drifting ice floes, a great visual but not quite the whole story.)

And then the percentages drop:

63 percent - will harm people in developing countries

58 percent - will harm people in the U.S.

40 percent - will harm me personally.

Perhaps, when politicians hear Lubber's message and go beyond the red state/blue state paradigm, the brakes will be off, doubts about real science will be erased and the work the panels discussed will be supported by the larger community.