Ida’s fatal power didn’t shock scientists who study how climate change primed the pump

[This article was originally published by The Philadelphia Inquirer]

Broadsided by floods and powerful tornadoes, the Philadelphia region was stunned by Ida’s deadly intensity.

But to scientists, clues were abundant Ida might prove formidable when it made landfall near Port Fourchon, La., as a Category 4 hurricane on Aug. 29. The scene was set 1,100 miles away for it to make history here three days later. The Philadelphia region was already pumped full of water and primed by heat to make whatever remnant tracked its way even worse — a signature of climate change.

Consider that as Ida was forming in the tropics in late August, Philly’s weather had been much hotter and wetter than normal all month. The average temperature was 79.2 degrees -- 2.3 degrees above normal. And 6.18 inches of rain had fallen, 144% over the average for the last 20 years.

Climate experts and a growing chorus of political leaders agree climate change can make the impact of storms far more dramatic and even deadly.

”Ida fed on an extreme level of heat content in the Gulf of Mexico,” Michael Mann, a Penn State climate scientist and director of the school’s Earth System Science Center, said in an email. “That record heat is tied directly to human-caused warming. That heat favored the dramatic, rapid intensification of Ida. So in short, yeah — this is climate change.”

Jessica Spaccio, a climatologist at the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell, says there’s little doubt climate change contributed to Ida’s power.

“To what degree is a harder question to answer,” Spaccio said. “But that it played a role is not a question. We are in a warming world. These storms are just so devastating. We definitely need to take climate change seriously and adapt.”

“Some people say Ida would not have happened if not for climate change. Well, that’s not true,” said Sean Sublette, a meteorologist with Climate Central, a nonprofit comprising scientists and journalists. “But climate change was unquestionably a factor.”

Sublette estimates that Philly likely got 10% more rain than it would have had if it weren’t for climate change. Warmer, wetter conditions do more than increase rainfall; they might be enough to push a hurricane’s wind speeds from a Category 3 to a much more destructive 4.

“When we try to quantify how much rain came down as a result of climate change it is exceedingly difficult,” Sublette said. “It might have rained like hell anyway. But instead of a near-record flood, you got a record flood. So instead of getting an inch or two of flooding on the Vine Street Expressway, you get enough for people to jump in and float.”

Scientists also agree that events like Ida are not freak occurrences.

“We’ve shown that these extreme floods are becoming more common in the past several decades,” said Dartmouth earth sciences researcher Evan Dethier, who lived in Philadelphia for several years. “There’s not really any reason for us right now to believe that they won’t continue to do so.”

Climate change and weather

Weather is defined as a single meteorological event, perhaps spanning days or weeks. Climate spans decades or longer. So it’s overly simplistic to blame every bad day on climate change. What scientists look for are patterns.

Scientists say the connection between warming and climate change is well understood. A warmer, moister atmosphere generates more energy for storms to feed on. Based on an Inquirer analysis of moisture in the air, as measured by the dew points, 2021 was likely the muggiest summer since 1995.

Looking at data from the last 50 years, Augusts in Philadelphia are getting hotter, leading to a 1.8-degree increase in average temperatures. And more days are cresting 90 degrees.

So, a rainstorm that might have dumped 5 inches without a changed climate might dump 6 inches. While that might not seem like much, it translates to millions of gallons of additional water flowing into regional waterways.

Precisely how climate change could contribute to tornadoes is trickier to establish, Sublette said. Cornell’s Spaccio said more research is needed.

Though the United States has not experienced an increase in days of tornado outbreaks, on days when there are outbreaks, more tornadoes are spawned than in the past.

That’s what happened here. On Wednesday evening, seven tornadoes struck the Philly region. Tornado ratings are based on the EF scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest winds. The tornado that struck Gloucester County was an EF-3 with peak winds of 150 mph and carved a 12-mile path, well over a typical path of 1.5 miles. Though EF-3s are rare in the region, consider that one struck Bensalem Township on July 29.

But even before Wednesday, tornadoes already were accelerating in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Swimming in sewage

As big as Ida may seem, consider it was only little more than a year ago that remnants of Hurricane Isaias dumped 9 inches of rain in some local areas, caused the Schuylkill to overflow, flooded Boathouse Row, ruined homes in the city’s Eastwick neighborhood, and even trapped a dredge barge at the I-676 ramp to I-76 in Center City, forcing the road to close.

During Ida, the Schuylkill at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia rose to 16.28 feet. Flood stage is nine feet, and 14 feet is considered a major flood. The average flow at the location is 1,460 cubic feet per second. It reached a flow of 125,000 cubic feet per second on Thursday.

Dozens of sewage and storm-water pipes overflowed, emptying untreated water directly into Philadelphia’s major waterways. So if you saw pictures on social media of people diving into the water and paddling around for fun, they were almost assuredly swimming in diluted sewage.

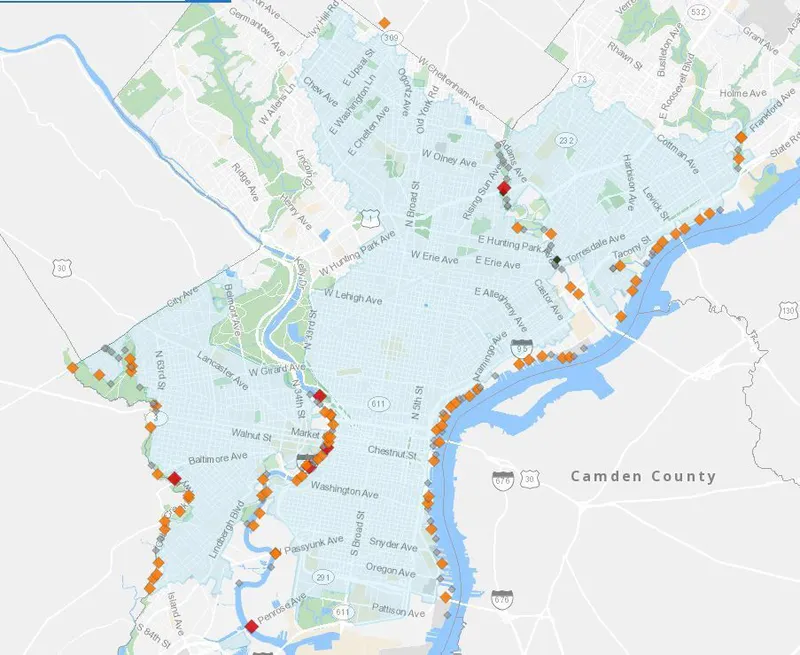

During big storms, 60% of the city’s aging sewage lines are designed to bypass at-capacity water treatment plants and flow directly into the Delaware River and the Schuylkill, as well as creeks such as the Tacony.

Philadelphia is not alone in its aging storm-water system. As climate change makes storms heavier, officials from around the region fear their systems won’t be able to keep up.

The damage from more intense storms gets even more expensive because of development near waterways. Water runs over paved surfaces directly into streams and rivers instead of being absorbed into the ground. Aging storm systems were not designed to handle such heavy loads.

Like other scientists, Dethier said he can’t “explicitly connect” the size of Ida to climate change. But the storm is part of the “dominant signal” researchers are seeing, given the sogginess of the Northeast this summer.

“It’s sort of like the precursor to having a big event like this,” Dethier said. “Because if you get eight inches of rain, but it’s been really dry, you might be able to absorb it and it might result in a minor flood. But in this case, it’s sort of like the system was primed to have a big event. We had the rain from Ida that just pushed it over the top.”

Another point of universal agreement: Preparing for more Idas will cost billions in infrastructure improvements. AccuWeather estimates Ida caused $95 billion in damage.

As Gov. Phil Murphy toured an area of Gloucester County devastated by a tornado spawned during Ida, he said he hopes Congress approves the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill to pay for roads, bridges, and utility systems that can handle ever-bigger storms.

“The world is changing,” Murphy said. “These storms are coming in more frequently, they’re coming in with more intensity. ... We have got to get a leap forward and get out ahead of this.”

Sen. Bob Casey, who also toured flood damage, agreed.

”I don’t think anyone should have any doubts in the aftermath of this storm about the gravity of the threat that we face from climate change,” Casey said.

Staff writer Laura McCrystal contributed to this article.