Whitewater fans fear change at Lehigh dam, wonder why New York City is involved

Kenneth Powley, owner of Whitewater Challengers, at the Francis E. Walter Dam and Reservoir in White Haven, Pa. Boaters, anglers, and residents are concerned about a study the dam's owner, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is conducting that could lead to changes in water flow. PHOTO BY FRANK KUMMER

This article was originally published by The Philadelphia Inquirer, one of our "From the Source" collaborators.

Ken Powley was a writer living in Philadelphia’s Mount Airy neighborhood in 1976 when he began taking people to the Lehigh River for guided rafting trips, charging only for gas.

Powley was stunned by how quickly those trips grew into a business, Whitewater Challengers, based in White Haven, Luzerne County.

The rafting depends on regular releases, from May to September, of waters held back by the Francis E. Walter dam, managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The reservoir created by the 1961 dam draws 246,000 visitors a year to Carbon and Luzerne Counties.

But Powley, now 70, is concerned his business will evaporate if an Army Corps reevaluation study of the dam leads to changes in how and when water gets released.

If the river stops churning, “we’d be done,” Powley, who employs 250 during the season, said with a grimace on a recent day as he stood atop the dam.

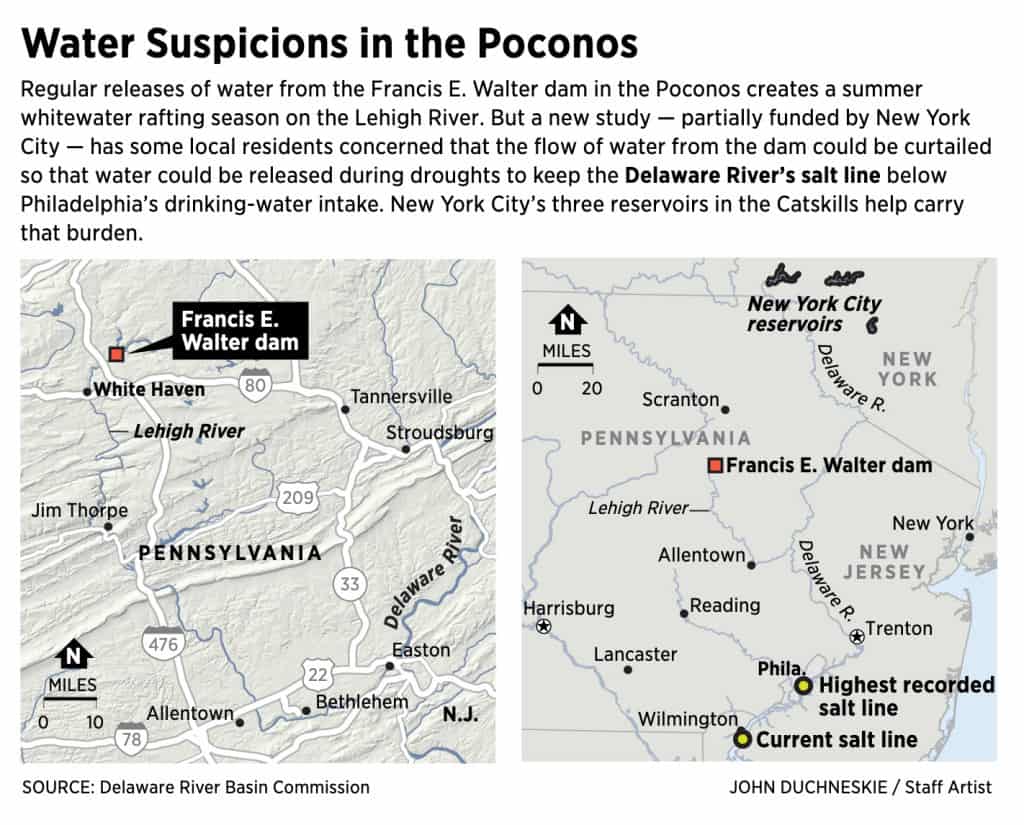

The dam was built to control flood risk. Recreation, like rafting, was added later as a purpose. Now, the Army Corps is looking at more uses for the dam, including how it could manage water flows to control the point at which salt creeps up the Delaware River. Keeping that salt line in place, well south of Philadelphia, is vital to protecting the city’s drinking water.

The 109-mile-long Lehigh is the Delaware River’s second largest tributary, releasing millions of gallons of freshwater daily into the river.

The three-year dam study, funded by the multistate Delaware River Basin Commission and the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, has just started. New York City is involved, in part, because it’s required to release its own reservoir water during times of drought to help keep the Delaware River salt line in check.

Though city officials deny it, locals like Powley are worried that New York would end up influencing how and when the water is released into the Lehigh River — essential to maintaining tourist-drawing recreation. Residents said the reach of the study wasn’t clearly communicated, leaving them to wonder how they might be affected by any changes it suggests.

The issue is so hot, 600 people packed a Jan. 9 public meeting in White Haven about the dam. Local residents, plus representatives from the Philadelphia Water Department, the Sierra Club, Lehigh Coldwater Fishery Alliance, and other organizations were there; so were state and local politicians.

It’s not the water, it’s the salt

The governors of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware all are part of the basin commission and are responsible for the Delaware River’s 330-mile flow.

If freshwater flow to the Delaware River gets too low, river managers explained, salt from the Delaware Estuary — fed by the Atlantic Ocean’s tides between Cape May and Lewes, Del. — could push farther upriver. That would contaminate Philadelphia’s drinking water supply.

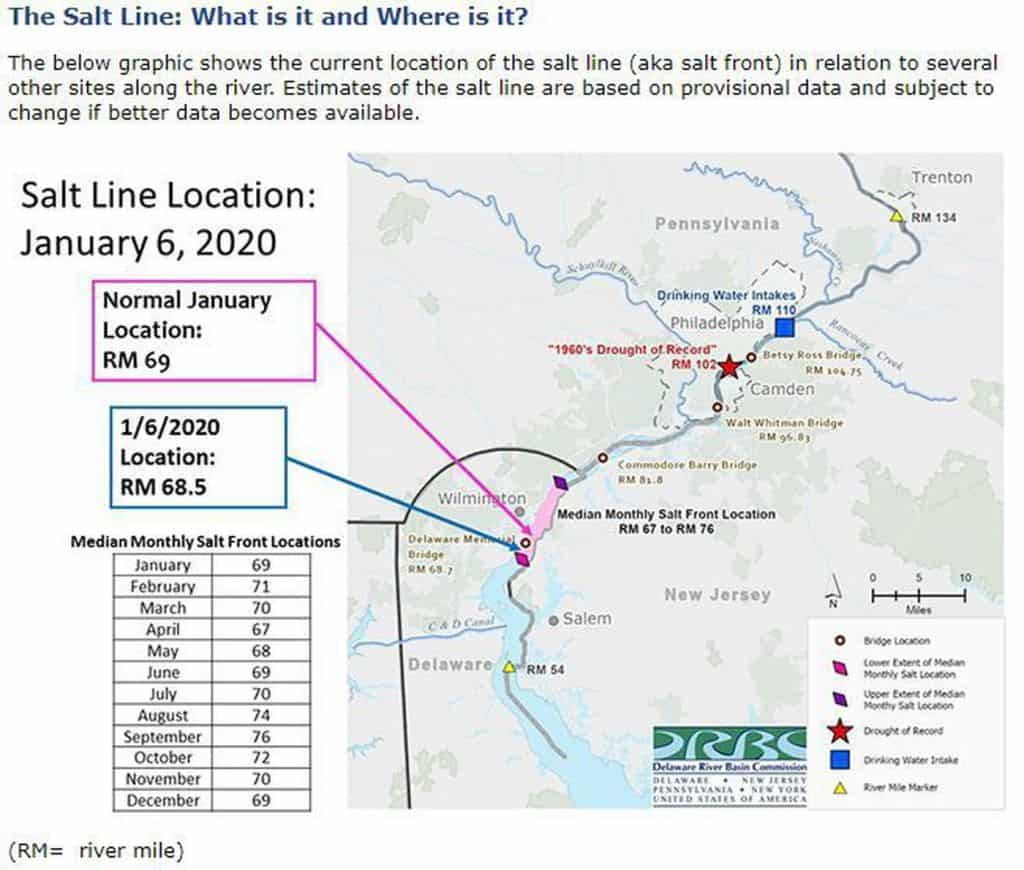

The salt line is one of the most watched barometers of the Delaware’s health, and New York is among the players involved in protecting it. And that’s why many who live and work near the dam are suspicious.

Primarily, New York City uses three reservoirs at the headwaters in New York’s Catskills for drinking water. But, under a federal agreement, during droughts the city also must release enough freshwater from its reservoirs to help keep the Delaware salt line away from Philly. Federal officials also draw on other reservoirs in the watershed.

Normally, the salt line remains near Wilmington. But in a record drought in the 1960s, it moved as far up as Camden, just below Philadelphia’s drinking water intake. Currently, the salt line is in its normal location, helped by a wet few years.

If a drought strikes again, like it almost did in 2016, New York could be on the hook to divert water from its upstream reservoirs to help keep the salt line at bay downstream.

Currently, water from the Francis E. Walter dam is not being used for salt line control. But the study parameters suggest officials are looking at that possibility.

Powley fears that if that happens, regularly scheduled dam releases into the Lehigh for recreational purposes could be severely curtailed or stopped, and the whitewater would stop churning, he said.

At the meeting, Paul Rush, deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, said his agency believes the Francis E. Walter dam could provide additional help with salt line control, but the issue needs to be studied.

New York, he said, does not want to actively control the dam’s operations. Nor, he insisted, does the city need another drinking water supply — another rumor that ran rampant before the meeting.

“We have plenty of water in our reservoirs to maintain the city’s needs way into the future,” Rush said.

He said water use is down in New York City from 1.6 billion gallons a day in 1979 to 1.1 billion gallons a day now because of low flow toilets, showers and other conservation measures.

Dan Caprioli, a project manager for the Army Corps, said he did not believe New York City has any “underlying motives,” calling the idea of piping water to New York for drinking “kind of crazy.”

Caprioli also said he believes flow from the dam can be used for salt control without harming recreation on the Lehigh.

Lehigh as fishing haven

Mike Stanislaw, of the Lehigh Coldwater Fishery Alliance, is watching the issue intently. He said trout thrive on cold water that gets released from the dam, traveling the Lehigh to its confluence with the Delaware River in Easton.

“We’re going to make sure we get some minimum flows,” Stanislaw said before the Jan. 9 meeting. “There is an established trout fishery in the Lehigh River, so we’re interested in improving and protecting it. It’s bringing in fishermen and tourists.”

Stanislaw said his organization would prefer structural changes to the dam that would allow for more releases of cold water, drawn from the bottom of the reservoir, so that it doesn’t run out as normally happens by July. Stanislaw said additional fishing could bring in millions of tourism dollars.

But reconfiguring the dam to create another tier of cold water could be expensive. Regardless, the groups also want to ensure that at least the current amount of cold water keeps flowing.

Stanislaw called the meeting “a positive step” and said that the Army Corps is “being genuine in its approach to ensure the study is grounded in fact-based science.”

Powley said the agencies haven’t revealed much about what the study is trying to accomplish. But he said he was encouraged by the turnout for the meeting and support his industry received.

Both he and Stanislaw say they intend to do all they can to ensure that locals don’t lose more control over the clean, pure waters that help lure so many to the Pocono Mountains.

Very interesting and InformativeThank you