DRBC report: ‘No measurable change’ to Delaware tributary’s water quality

Looking south at the Delaware River, from Belvidere, N.J.. The Pequest River flows into the Delaware at the lower left of the photo. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

The Belvidere Bridge, from the New Jersey side, operated by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. This bridge is free, following the pattern that free bridges and toll bridges alternate up the river. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

ONE OF THE RECENT Delaware River Basin Commission's scientific reports is cause for celebration among Delaware River enthusiasts, but it needs to be parsed in order to be celebrated.

Essentially, the news is that the river water in a 76-mile stretch from Portland Pa./Columbia, N.J., to Trenton, N.J. did not get worse in the approximately 10-year span of sampling.

You might be tempted to think, "No biggie." But wait.

This particular stretch includes the Lehigh River, one of the larger rivers that flow into the Delaware, and the Lehigh is a complicated river. This is how Kate Schmidt from the DRBC described it: "The Lehigh is a complex watershed with an industrial legacy, reservoirs, complex geology, and a high level of development including wastewater treatment."

So this report isn't about some quiet backwater but a working river, so the parameters may not reach ideal standards, but this is a way to insure nothing gets worse, and maybe gets better.

In this report — Assessment of Measurable Changes to Existing Water Quality, Round 1: Baseline EWQ (2000-2004) vs. Post-EWQ (2009-2011) — the DRBC compared samples taken in the time period 2000-2004 (which established a baseline) to samples taken from 2009-2011. Find the full report here.

"No measurable change took place for 17 out of 20 parameters tested at almost all control points in the recent 2009-2011 assessment period," the report states. There are 24 testing sites in all, with nine on the main stem and 15 on important tributaries.

That is evidence enough, said Steve Tambini, the executive director of the DRBC, that the "Special Protection Waters program is working."

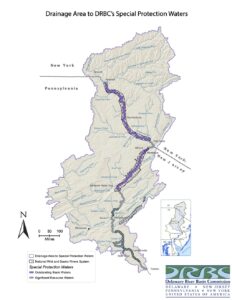

COURTESY DRBC.NET

The Special Protection Waters classification includes the river from Trenton all the way up to where the river begins in Hancock, N.Y. This was developed by the DRBC to insure that what are called "high quality" waters stay that way.

By creating this designation, what the DRBC did was unique among U.S. rivers. It put a lid on how degraded (that's science speak for "worse") these waters can become. Also, it created a watershed-wide lens to look at, not just the river, but all the waters that flow into it.

And while we're giving out gold stars, it should be noted that the idea to add this section of the river to the SPW program came from a petition filed in 2001 by the Delaware Riverkeeper Network. The petition was itself a follow-up to a federal designation in 2000 that added this section to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Much of the river above this stretch is in the Wild and Scenic Systems and in the National Park Service.

The National Park Service is a partner with the DRBC in the monitoring program that yielded this report — the Scenic Rivers Monitoring Program.

The National Park Service has been doing its own monitoring of the parks above this 76-mile stretch for years, in fact there's a website that can give you a peek at the work that's done for the parks.

According to Allan Ambler, a biologist at the Delaware Water Gap Natural Recreation Area, they have baseline data gathered, just as the DRBC did in 2000-2004, and are awaiting funding to complete the monitoring to do the second set of sampling.

Here's the detail of the data recently reported by the DRBC:

(The parameters) include general water quality parameters such as alkalinity, hardness, pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, turbidity, dissolved and suspended solids, all nutrient forms (ammonia, nitrate+nitrite, total nitrogen, total phosphorous, and orthophosphate.) Two out of three bacteria parameters (Enterococcus and Fecal coliforms) showed no measurable change.

It should be noted that all seven of the parameters including all nutrient parameters that are evaluated for wastewater treatment facilities are included in this group.

Measurable change toward degraded water quality was detected for three parameters: chlorides and specific conductance at almost all sites, and for E. coli at sites from Nishisakawick Creek in Frenchtown, N.J., and downstream.

Schmidt explained that specific conductance is a measure of how well water can conduct an electrical current. Conductivity increases with the presence of ions, for example, chlorides.

Also, E.coli can be found in both animal and human waste, Schmidt said. "Human waste is treated via sewage treatment plants, animal waste is not. There is a hypothesis that the elevated E.coli numbers can be attributed to geese, but this is still a hypothesis at this time."

To combat these issues the DRBC will recommend, Schmidt said, "Bacterial track-down studies to look more into the bacteria issue and will also recommend that discussions with our basin states and advisory committees be initiated to identify and implement ways to reduce chloride concentrations and stream conductivity."

Some of the dangerous pollutants that we have become more aware of — the PFASs, PFCs, PPCPs, etc. — aren't included in this report. Schmidt explained:

"Our efforts on contaminants of emerging concern (PFASs, PFCs, PPCPs, etc.) are ongoing and continue to evolve in coordination with the states. Analytical costs for compounds like PFASs and PFCs are quite high. Therefore, establishing EWQ (existing water quality) targets, which is very monitoring intensive, for PFAS and PFCs may not be the most effective approach for addressing these pollutants."

Visit the DRBC's page about CEC's (contaminants of emerging concern) here.