USGS relies on historic gage to gauge optimum flow for Delaware

The door at the base of tower reveals nothing too spectacular — down below is the stilling well. And around to the far right, is a huge camera-shy spider. Trainor says they usually find at least one really big spider at most of the gages. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

he Montague gage stands on the shores of the Delaware River in Milford Pa. The United States Geological Survey uses various measurements to estimate how much water is in the Delaware River right here. The new Milford-Montague bridge is in the background. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

Hydrologists Jerilyn Collenburg, left, and John Trainor, right, start an hours-long process of measuring the river by boat. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

The sign on the door at the bottom of the tower in Milford, Pa. This gage is in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

The two USGS hydrologists, Jerilyn Collenburg, left, and John Trainor, right, stand on the banks of the Delaware River as they pump the intakes for the stilling well clear. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

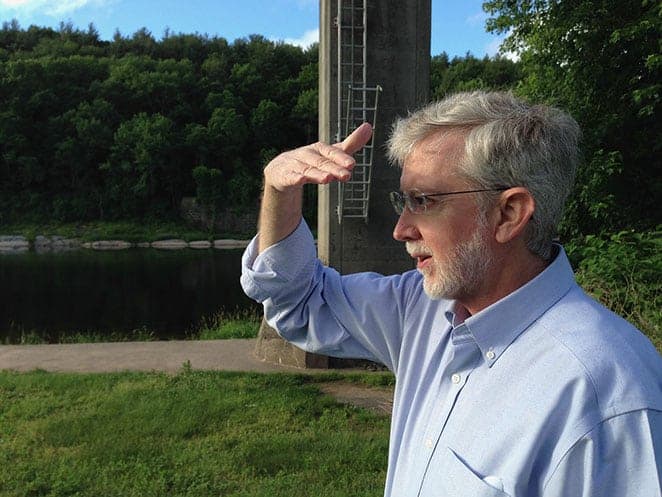

Robert Mason, the Delaware River Master, peers up river as if to see what's happening far upstream. Failing a crystal ball and some magic, he relies on historical records and current measurements to help predict how much water there might be in the river tomorrow. The tower of the Montague gage is in the background. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

IT'S A BRIGHT AND sunny day in June, and the river is doing its thing — sometimes a little higher, today seems a little lower. Here at the beach in Milford, Pa. nothing seems out of the ordinary, except maybe the 30-foot concrete tower that stands sentinel on the river's edge, almost hidden by trees.

This river has a lot of people and machines making it look just about the same most days. And that tower is well known to fans of the Delaware River: it's the Montague gage.

Yes, I know that Montague is across the river in New Jersey. But I checked with the United States Geological Survey and it says yep, this is that gage.

The gage (by the way, the USGS prefers this spelling) is one of the key measuring points to determine how much water is in the river. That's important because downriver of Montague (or Milford) are the thirsty cities of Trenton and Philadelphia, as well as a host of smaller towns that draw their water from the river.

In the 1950s when the four river states were once again at odds about how much New York City was taking from the headwaters of the Delaware River, the Supreme Court re-visited the case it had originally heard in 1930/31 and created an amended decree that said that the water at the Montague gage had to be at a certain flow or quantity and if it fell below that quantity, releases had to be made from New York City's reservoirs so that there would be enough water for everyone. That is an over-simplification, and you can read the fine print here.

Jerilyn Collenburg, a hydrologist with the USGS, checks records and accuracy of data. PHOTO BY MEG McGUIRE

The two hydrologic technicians — Jerilyn Collenburg and John Trainor — in Milford today to check the gage and see that it was functioning properly weren't aware that they were dealing with a super star. But that's not surprising, really. The USGS is relied on by all sorts of government departments in many states to be the accurate providers of information about water — an especially valuable commodity out West. Conflicts aren't what the USGS is interested in. Just data.

Accuracy is a big deal for the USGS, and as a corollary to that, accurate historical records.

The USGS measures and records Delaware River water flow all the time, remotely, using a variety of instruments perched on the top of this tower. In fact, there are several important gages along the river, with the Delaware River Basin Commission paying close attention to this gage and to the one that's operated by the USGS in Trenton, NJ. These gages help evaluate the impact of the streams and rivers that flow into the Delaware as well as the water drawn out. The DRBC has the authority to declare a drought in the whole watershed, and it uses these gages and historical records — and the interpretative knowledge of the USGS —to come to that decision.

Back to Montague/Milford: Collenburg and Trainor are surface water experts and it doesn't take long for them to plunge into explanations about how they do what they do that can leave a neophyte bewildered.

It seems that there are two "parts" to finding out how much water is flowing by us. The first is the height of the river, called stage. That one makes sense — and the machinery permanently at the site is recording height information constantly. This gage uses a stilling well, which records the height of water that wells up inside the tower. One of their jobs today is to clear out the tubes that transmit the water to the stilling well. There is also the most primitive of measurements — a nail deep in a rock beside the river (see photo).This one is pretty easy to understand.

Collenburg and Trainor take on-site measurements and later, when they return to their headquarters (New Jersey Water Science Center in Lawrenceville, N.J.) they will see how well those measurements compare with those transmitted, a double safeguard.

This gage has an interesting history. It was once attached to a bridge that crossed the Delaware here. You can see the other tower across the river — and no sign of the roadway that led to it. The bridge made access to the instruments at the top of the tower easy. You could just walk to it. That bridge was replaced by the Milford bridge less than a mile away. Now if there are problems with the gage, someone has to climb a ladder on the side of the tower and get harnessed in for safety reasons.

Needless to say, Collenburg is hoping no such aerial gymnastics are required! (They weren't.)

The other piece of the "how much water" is a little trickier. It's called discharge. One of the best ways to understand it is Collenburg's explanation of why the USGS comes back to this site every two weeks in the summer. That's when the vegetation in the river can impede the flow of water. So the water level might be the same as in early spring, but the amount of water won't be the same.

But it's not just what's in the water that can affect discharge. It's also what can happen to the river bottom. If there were a big storm, for example, the rush of water could not only erode soft silt but also move fairly big rocks and shove them down stream or even to the river bank.

To measure discharge, the two hydrologists will board a small boat and spend a couple of hours trawling back and forth across the river, taking readings of the river's bed. The readings give a sense of how big the river is at that point and how fast the water is running.

"How much water" is calculated by what's called the stage/discharge relationship. More discussion about this can be found at nj.usgs.gov. It's fascinating. And there's maps of other gages and other interesting data.

The magic number is 1,750 cubic feet per second, the minimum stipulated by the Supreme Court amended decree, which also created a new job: the Delaware River Master. Right now, Robert Mason holds that title. He is also the chief of the Surface Water section of the USGS and is based at its national headquarters in Washington, DC.

About a week after the hydrologists' visit, Mason was up in the watershed to inspect several other USGS streamgages downstream of the New York City Delaware River reservoirs. Though the City meters portions of the diversions and releases from its reservoirs, Mason and his staff use independent USGS streamgages and additional USGS flow measurements to verify the NYC records and account for additional diversions and releases, even during floods.

But the records from the past two to three days are likely the most important in the day-to-day running of the river. The water here today has been gathering for several days from all points upstream. It's the comparison of what's been happening upstream to Montague that allows the river master to request more or less water from the river's primary source, the NYC reservoirs. After all, there's no tap to turn water on or off at Montague.

Though Mason clearly respects the role the Supreme Court devised, he'd rather emphasize the role that the day-in, day-out hydrologic technicians play. Certainly it's the combination of present records and previous ones that allow him to do his job, which is to administer the provisions of the amended decree relating to the yields, diversions and releases of water from the New York City reservoirs. More on this from the site of the Delaware River Master.

Embedded in that "administration," is the responsibility to ascertain where the water in the river at Montague is coming from. That includes controlled water releases from the NYC reservoirs, as well as spills when the reservoirs are full. (Is your head spinning yet?) The investigative work also includes the uncontrolled runoff from upriver streams as well as releases from hydroelectric stations at Lake Wallenpaupack and the Rio Reservoir on the Mongaup River.

The river master has to report to the Supreme Court with copies to the governors of the four states and the mayor of New York City.

When Mason took on this role in February 2013, he was briefed on his duties by the United States Solicitor General, who is the legal representative of the U.S. in cases before the Supreme Court. The Solicitor General is the third highest-ranking official in the US Department of Justice.

Mason asked about the other river masters in the U.S. so that he could have a way to get to know his job better.

There aren't any other river masters, he was told.

Only the Delaware has a river master, which gives you a sense of just how important this job— and this river — is.